by Anna Spence

From the murky depths of blackness appears Max Headroom, floating to the surface. Suddenly, his decayed visage snaps into place where it always should have been: on screen. Out of practice, it takes him a moment to notice our presence, but once he does, he begins to chat, as if we are old friends.

Max is trying to remember a past life. Scanning the backlogs of his memory, he decided to start from the beginning. But whatever sense he can grasp soon slips through his fingers like water. Suddenly, a flush of life. As we continue to watch Max (and as he continues to watch us), life returns to his face. It is in this moment that he realizes what it will take to break free from his purgatory.

- 20 Minutes Into The Future

In one of my earliest memories, Max explodes onto our TV screen, huge and loud. At 3, I had never seen anyone like him. He wasn’t quite a dad, but he wasn’t a clown either. He was somewhere in between the two, except he was from the future. Twenty-nine years after he left the airwaves, I still wonder if Max Headroom lived on a different timeline than everyone else. Maybe the world wasn’t prepared for him? Or maybe the tech evolved so quickly that he couldn’t keep up. Either way, for me, he has come to symbolize the promise of a future that has yet to materialize. In the following, I will discuss the concepts, art pieces, and ideas that informed the creation of 20 Past-Future.

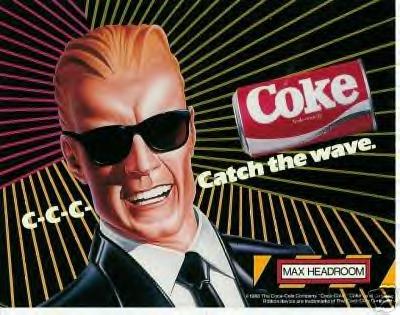

Max Headroom is a fictional character introduced fittingly enough in 1984 as “The World’s first computer-generated TV host”. Max Headroom originally appeared in the British TV movie, Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future which was broadcast in 1985. After its success, the character was spun off into a veejay in the British music video program, The Max Headroom Show, which quickly became a cult hit. A second season was produced in late 1985, and a third and final season ran in 1986.The Max Headroom character also hosted an interview show on Cinemax, called The Original Max Talking Headroom Show. Outside the television series Max became the spokesman for New Coke, and in the UK, appeared in television commercials for Radio Rentals. Ultimately, Max couldn’t compete with shows like Dallas and Miami Vice and his show was soon cancelled by ABC.

Max Headroom is a fictional character introduced fittingly enough in 1984 as “The World’s first computer-generated TV host”. Max Headroom originally appeared in the British TV movie, Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future which was broadcast in 1985. After its success, the character was spun off into a veejay in the British music video program, The Max Headroom Show, which quickly became a cult hit. A second season was produced in late 1985, and a third and final season ran in 1986.The Max Headroom character also hosted an interview show on Cinemax, called The Original Max Talking Headroom Show. Outside the television series Max became the spokesman for New Coke, and in the UK, appeared in television commercials for Radio Rentals. Ultimately, Max couldn’t compete with shows like Dallas and Miami Vice and his show was soon cancelled by ABC.

This is where I find Max today–20 minutes after the future–after his show got cancelled, after the DTV switch (in which TV broadcasting signals transitioned from analog to digital). Here, he is a phantasmatic apparition, summoned to the screen every time the video plays. He talks to the audience as he struggles to remember his first memory. As he begins to discuss his past (when his show was still on air) and his present, Max’s memories begin to come back to him. At the end of the piece, Max begins to remember what it felt like to be alive.

- After The Collapse

Max Headroom embodied a speculative future by signifying the promise of technological advancement just over the horizon where self-governing machines take a larger role in society. 1985’s Max Headroom: 20 Minutes into the Future introduces Edison Carter, a television reporter who suffered a serious head injury, when he struck a low-clearance sign labelled “Max. Headroom 2.3m”. Bryce Lynch, a scientist, suggests that the network generates a computerized version of the reporter by uploading Carter’s mind to a computer mainframe. Soon, the computer program takes on a life of its own and Max Headroom is born.

It’s important to remember that Max is computer-generated and when he’s not on screen, he’s surfing the airwaves as electronic data. His whole existence is transmissional, forever in the act of becoming.[1] Considering this, what would have happened to him in 2009, when the television signal he calls home switched from analog to a digital? Would he, too, make the transition, or would he be trapped in analog ruin for the rest of time?

Artist Rosa Menkman considers issues regarding the DTV switch in her piece, “The Collapse of PAL”, a live, televised, video performance which she staged on May 25th, 2010, utilizing the dying PAL signal. In this, the Angel of History reflects on the PAL signal and its demise. While it might be argued that the PAL signal is dead, Menkman maintains that it still exists, albeit as a trace imprinted upon new, better (digital) technologies.

The performance reflects on different significant aspects of the changing conditions of broadcasting. In the new DVB-T (digital terrestrial television) environment, the very transmission format of TV has changed, from symmetric analog to asymmetric data flows, encoded in the MPEG format and decoded through software implemented in everything from flat-screen TVs, set-top-boxes and PCs. ‘The cracking of LCD screens’…all is not smoothe in this world of digitally compressed TV. [2]

Like Menkman, I consider possible implications of the demise of an already dying technology. However, at the heart of my piece, it’s about Max, and the role he adopts in the relationship between the viewer and the moving image.

- Conjuring Max Headroom

Phantasm (noun)-1. an apparition or specter. 2. a creation of the imagination or fancy; fantasy. 3. a mental image or representation of a real object. 4.an illusory likeness of something.

Lately, as I consider the moving image, I often find myself returning to its intangibility. Moving images are visions. They are fleeting. While they can be profoundly compelling, they’re only traces. Video leaves no footprint.

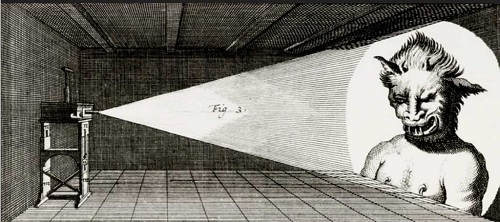

While some sightings of gods and spirits are thought to have been conjured by means of mirrors, camera obscura, or magic lantern projections, the technique for producing such images came to the forefront in a type of horror theater called “phantasmagoria” during the 18th and 19th centuries. By using magic lanterns to create scary images of skeletons, demons or ghosts, self-styled necromancers would summon spirits from hell, terrifying the audience. [3]

The magic lantern was an ideal mechanism to project these otherworldly illusions since the imagery it produced was not tangible. When standing in front of a painting or a sculpture, it is easy to approximate “where” the art happens. But with moving images, the answers are not so clear cut.

In her article, “The Voice In the Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space”[4], film theorist Mary Ann Doane describes the moving image as a heterogeneous entity comprised of sound and image. She describes a phantasmatic body – a unified presence made manifest through cinematic technology.

“ However, the body reconstituted by the technology and practices of the cinema is a phantasmatic body, which offers support as well as a point of identification for the subject addressed by the film.”(p.373-374).

The idea to portray Max as a phantasmatic entity seemed fitting in light of his transmissional nature. Max mimics us with a few trademarks of human existence, but the crucial difference between us is that Max is constantly engaged in the act of becoming- he will not die. Because of this, it seemed necessary to simultaneously erase and reinforce the borders between man and machine. As the unity of image and sound in film constitutes a body of its own, it made sense to highlight this phantasmatic nature of Max’s body.

- The Place Where Signification Intrudes

When considering “where” the moving image takes place (or in Doane’s case, where the phantasmatic body materializes), it becomes clear that cinema doesn’t need the black box, as much as the black box needs it. The power at the heart of the medium is not necessarily found in its nuts and bolts, but within the type of relationship it is able to establish with its viewer.

The implications of the viewer/cinema relationship are many times magnified in the case of Max Headroom. Film or video takes on meaning only when a human perceives, and injects part of him or herself into it. Nebulous electronic data surfing the airwaves off screen, Max depends on the television broadcast to give him form, but most importantly, he depends on the audience to give him significance.

Characters only take on the substance we lend them, and within this process, they are activated. As we watch Max, we infuse the hollow framework of his likeness with our viewpoint on the world around us, formed by our knowledge, memories, experiences, thoughts, opinions, etc. It is only when we project these aspects of ourselves onto Max that he is revived. Now that his show has been cancelled, Max roves the airwaves searching for his own meaning, only to realize that his is dependent on ours.

[1] Barry, Judith. “Eyestrain.” Public Fantasy: An Anthology of Critical Essays, Fictions and Project Descriptions. London: ICA, 1991. 116. Print.

[2] http://classic.rhizome.org/portfolios/artwork/54452/

[3] In the 17th century, Jesuit mathematician and physicist François d‘Aguilon describes how charlatans used phantasmagoria as a way to cheat the gullible out of their money. Inside a dark room, these self-proclaimed necromancers would raise the specters of the devil from hell for the audience to see. Usually, this was image of an assistant wearing a devil’s mask, who was then projected through a lens into the dark room.

[4] Doane, Mary Ann. “The Voice In the Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space.”Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. Comp. Marshall Cohen. Sixth ed. New York, N.Y. ; Oxford: Oxford UP, 1999. 373-85. Print.