Artist and midwestern art & digital media professor Mike Mosher has contributed pieces on the Ann Arbor Film Festival (#15), on George Manupelli (#17), on Annalee Newitz (#21), on Jimm Juback (#23), and on Cary Loren (#24) to OTHERZINE. He painted community murals in San Francisco’s Mission when he lived four blocks from Other Cinema in 1981-85.

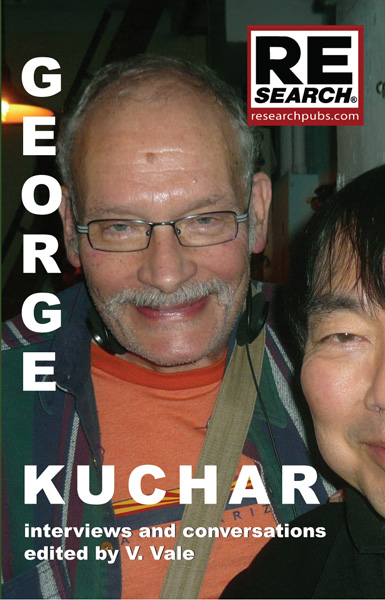

It was at Book Beat, the suburban Detroit bookstore co-owned by filmmaker Cary Loren that I was excited to see and buy the small paperback George Kuchar: Interviews and Conversations. Here’s George Kuchar, chatting amiably before his 2011 death with its editor V. Vale, or being talked about by his twin brother Mike, and by informed others.

It was at Book Beat, the suburban Detroit bookstore co-owned by filmmaker Cary Loren that I was excited to see and buy the small paperback George Kuchar: Interviews and Conversations. Here’s George Kuchar, chatting amiably before his 2011 death with its editor V. Vale, or being talked about by his twin brother Mike, and by informed others.

At Dartmouth College in the mid-1970s, a colleague and I lobbied to get the Kuchar brothers’ Sins of the Fleshapoids shown by the College Film Society. We were among the few there who appreciated Camp, the ethic of fey excess and put-on melodrama I had seen enliven often-amateurish offerings at the Ann Arbor Film Festival when I was in high school. In 1964, super-serious Susan Sontag wrote of Camp, “serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious. The essence of camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration. Camp sees everything in quotation marks. The ultimate camp statement is it’s good because it’s awful.” Meanwhile, many of my homeboys and homegirls in Michigan were, at that time, being made up and costumed to make Camp-infused movies with Loren, himself a devoted student of Flaming Creatures’ Jack Smith.

I arrived in San Francisco in the summer of 1978, just in time to lurk at the epicenter of Punk rock and art cultures on that coast, the SF Art Institute, where Kuchar taught 1971 to 2011. Nearby, I picked up Search and Destroy, the Punk tabloid edited and published by V. Vale and Andrea Juno. Whenever I walked down Sixteenth Street in the Mission in the early 1980s, I would invariably see George Kuchar. His student, collaborator, and lover Curt McDowell worked at the Roxie Cinema, a name I recognized since both George’s and Curt’s comic strips appeared in Arcade, the 1970s comix magazine co-edited by Robert Crumb and Art (“Maus”) Spiegelman, and which also often featured San Franciscan Bill Griffith’s “Zippy the Pinhead”, both of whom appeared in George’s movies. A certain wild, ad hoc and unrestrained aesthetic that might be called Kucharian ran wide and deep out here.

In the 1980s Juno and Vale turned their attention to quality paperback books from their REsearch Publications; their fine book on J. G. Ballard (1984) offered an excellent introduction to that author. Their Modern Primitives (1989) documented the world of tattoos and piercings a decade or more before those phenomena appeared at malls across the nation and the bodies of so many small-town teenagers. Juno and Vale’s publishing partnership broke up, and both Juno Books and Vale’s REsearch Publications continued to produce well-designed, interesting paperbacks. Vale has edited this affectionate pocket-sized George Kuchar volume.

The twins George and Mike Kuchar began their filmmaking in the 1950s with an 8 mm camera. They were taken to movies by their mother, as well as by her friend who liked foreign films, and got a 16mm camera in the early 1960s. George showed a humorous film about babies with birth defects from the soon-banned drug thalidomide at a New York 8mm club of elderly amateur filmmakers, and they gave him a bad review in their newsletter. George made Hold Me While I’m Naked in 1966, dubbing all the voices—male and female—himself, but was pleased to find synch sound equipment when he began teaching at the San Francisco Art Institute. When he saw Hold Me While I’m Naked at a luncheon put on by Red Grooms and art book publisher Harold Abrams, Andy Warhol suggested Kuchar go back to 8mm projects. Still, the movie came to be voted 52nd in the Village Voice Critics’ Poll of the 100 Best Movies of the 20th Century.

George Kuchar celebrates the editing skill of Hitchcock, the ad hoc aesthetic of Roger Corman under budget constraints, both committed to movies that would bring in crowds and make money. He likes to improvise with his cast of non-actors. “You generally know when a movie’s over when you don’t want to shoot anymore—’I’ve had enough of this’—and then pull the plug. Then you take the footage and assemble it in a way.” Any way? Perhaps. Whatever. He points out the importance of lighting, lugging lights or high-wattage bulbs to shoot a scene in a student’s nearby house or apartment borrowed for the afternoon. Walter Gutman, a banker and fan of muscular women who had produced Robert Frank’s Pull My Daisy and The Sins of Jesus financed Kuchar’s first feature film Unstrap Me.

Much of what George Kuchar tells Vale, he has before said in an essay he wrote in the book Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area 1945-2000, edited by Steve Anker, Kathy Geritz, and Steve Seid, University of California Press, 2010. In that book, Kuchar wrote of his “movie factory” in an essay splattered with trash, garbage and excrement motifs to humbly describe his work at the San Francisco Art Institute. “Making films was a way for me to sidestep the physical and psychological angst inherent in that place”, and scheduling his filmmaking classes in the academic “boondocks” of Fridays proved “more like therapy sessions than anything else”, when making movies with students was an “adventure in terror with some moments of horror thrown in.” Kuchar was proud the class would “grind the productions out from start to finish” to create “expression on a shoestring budget”. With Destination Damnation in 1972, they realized that creative use of makeup and colored lighting could best stretch a $200 budget. The Devil’s Cleavage and The Carnal Bipeds (both 1973) were in color, and with I Married a Heathen (1974) they graduated to 16mm. In the 1980s, he and his class regularly produced two films a year, and explored the mini DV format to make them in the 1990s.

In that same volume, Vale wrote “Bay Area Punk Film/Videomaking and the Emergence of Alternative Gallery/Club Venues”, where he credited George Kuchar with “appropriated ‘Grand Guignol’ musical soundtracks” in the Art Institute’s context of collage and found footage, and employment of Punk band members as actors. Around that time, Jennifer M. Kroot made her documentary on the brothers, It Came From Kuchar.

George Kuchar: Interviews and Conversations contains an annotated filmography- valuable for academics- and benefits from its serious research. There are tales of battles with flawed work prints and faulty splicers, editing as adventure and discovery, nuts and bolts experiences that led to an aesthetic of radical simplicity, chance and kismet. The first time I read this book I found it a bit unsatisfying; it wasn’t the fun and extreme book I expected from the guy from REsearch. I looked for camp, wit, San Franciscan detail, a bit more outrage or racy stories. Or, maybe George was simply tamer in daily life, evincing the pragmatism necessary to teach film by involving students in the making of movies for decades. At its best, this book is infused with the same feeling you get watching Tim Burton’s movie ED WOOD, an infectious love of moviemaking that makes the reader want to put down the book and grab the camera. John Waters has acknowledged Kuchar’s inspiration to make his own movies.

So, Kuchar’s advice, in a nutshell, to filmmakers? “…The main idea is to be friendly, and not have anybody feel intimidated, and just have a loose atmosphere, and then people will open up! That’s the main idea, to get everybody working together…You also have to have a really good time because it’s hard labor; there’s moving lights around, and if you’re working in a studio, dealing with a lot of things, picking things up and putting things into motion. So if you can have fun while you’re doing it, then everybody feels relaxed, and everybody puts out on the screen what they can give most, while being relaxed.”

I’ll put Vale’s little book of Kuchar on my shelf next to James Broughton’s Seeing the Light (City Lights, 1977), another Bay Area filmmaker who taught at the Art Institute. That eccentric poet, activist and also celebrant of queer aesthetics, wrote his little philosophy book on his own self-discovery (“illumination”) through film and early encounters with inspiring Frank Baum’s Oz books. Friend of Dorothy, indeed. Both are testaments to their human-scale creativity, manifested in long, ever-youthful lives in alternative filmmaking.

George Kuchar: Interviews and Conversations

Edited by V. Vale

2013, RE/Search Publications, San Francisco

www.researchpubs.com

Reviewed by Mike Mosher