Of all Edison’s creations, the kitten boxing gloves are the most marvelous. In the 1894 film Professor Welton’s Boxing Cats, two cats square off in a cat sized boxing ring and wield cat-sized boxing gloves. In the distance between the kitten boxers stands a human-sized human referee, who gives the competition a sense of scale and seriousness.

Taking place in the Black Maria Studio, this boxing match transposed the Edison Company’s perchance for animal violence from the literal stratum of elephant electrocution into the symbolic realm of the pet tournament. The Edison Company described this film as: “A glove contest between trained cats. A very comical and amusing subject, and is sure to create a great laugh” (Edison Films). This level of kitsch and humor would fit comfortably in contemporary forums such as Reddit and Imgur; one might describe the film as: “the first cat video ever.”

The magisterial referee in the middle is Professor Welton himself. Relying on sunlight the Black Maria was a more or less a modified green house and in this overhead lighting the Professor’s torso and body disappear. All that is known of the Professor and his doctorate is that he trains cats. In this tableau, he stands like the hidden figures of daguerreotypes that arrest their subject’s motion for the camera. He is like a disembodied Cheshire cat, because only his hands and head are revealed.

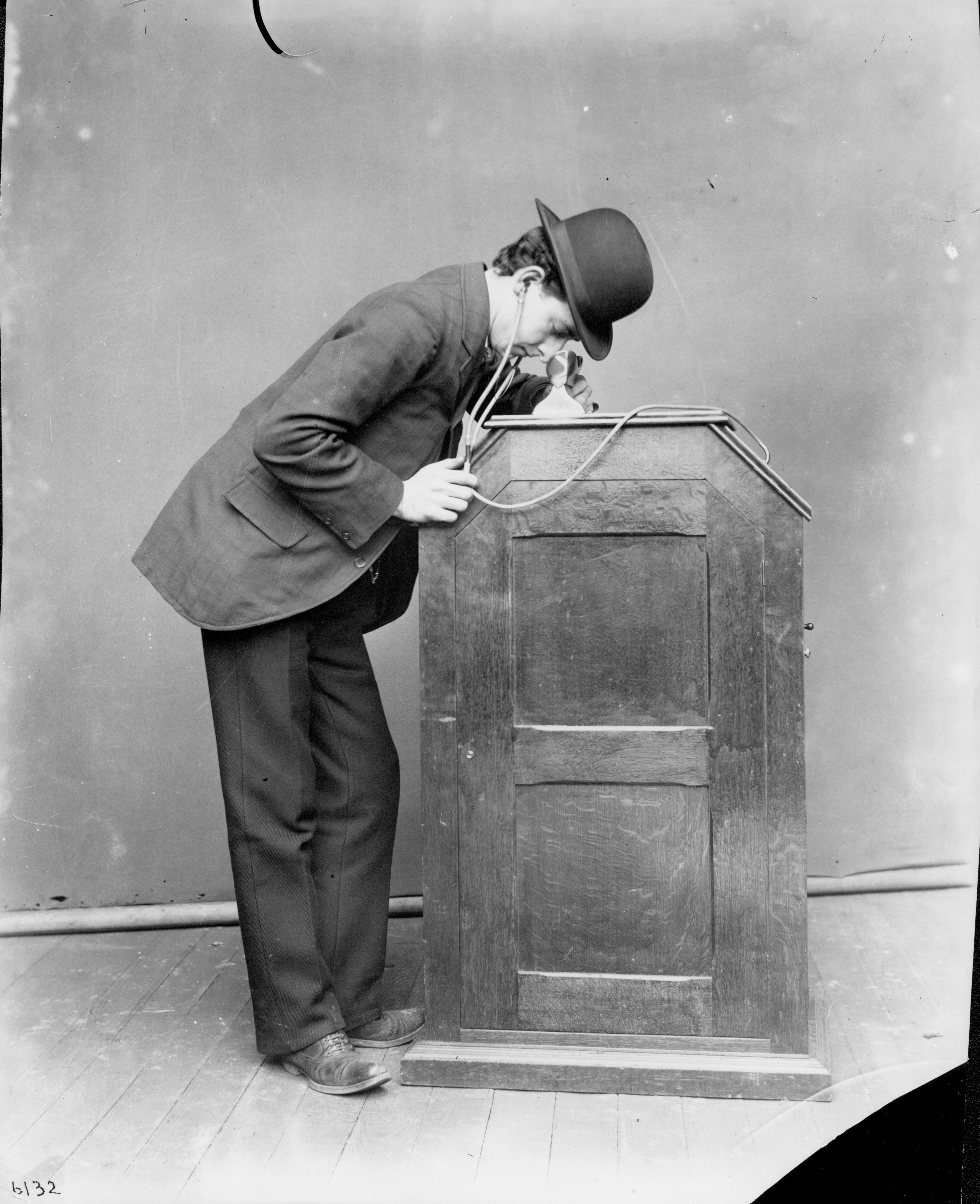

In addition to Boxing Cats dozens of short films were made at the Black Maria in the 1890’s. All bear the formal qualities of being a stationary shot, with few or no cuts and lasting only a minute or two. These films were shown in public parlors on the Edison Kinetoscope, a coin-operated device that preceded the theatrical projector. Each machine was only capable of showing one film at a time, on a loop. The Kinetescope was an elaboration on of Edward Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope, which was building on a host of other devices from the 19th century known as optical and philosophical toys. All of these proto-cinematic devices provided a viewing experience that was not public; but one that is individual, private and even intimate.

The 20th century sought to hide the projector in a booth, while the 19th century Kinetoscope placed the projector at center stage, in front of the spectator, and in fact hid the film. 19th century audiences were fascinated not only by the visual novelty of images in motion, but also the technology which made sync motion possible. This era of cinema is what film scholar Tom Gunning refers to as the Cinema of Attractions. A cinema sharing more with the spectacles of the amusement park or worlds fair then with the narrative tendencies of either literature or theatre. This spectacularist cinema dominated until 1907 when popular films began to harden into a narrative form we would recognize today. The Cinema of Attractions did not disappear completely though, but instead went underground, re-emerging in Avant Garde cinema and from time to time in feature films as “Spielberg-Lucas-Coppolla” cinema of effects (Gunning 61).”

Despite its popularity, the GIF is an anachronism of networked technology. It was developed in 1987 by CompuServe as a means to compress and transmit chunks of related images over private networks. In the early 1990’s, the World Wide Web became accessible to the general public it had tight bandwidth restrictions and was unable to display video or high resolution photographs. The animated GIF was used on early websites to display motion graphics and banner ads.

Like the Kinetoscope and the Cinema of Attractions, the GIF emerged during an era of innovation and the invention of a new technology. The GIF was an experimental gesture towards the replication of motion using a new technology: the personal computer. Historically and formally, the GIF is similar to the proto-cinematic machines of 19th century in that it is a loop intended not for public exhibition, but for individual viewing. It also contains mostly static perspectives, few cuts, and seeks to titillate – not narrate.

The Dancing Baby was a 1996 Internet meme passed around through e-mail and list serves as an animated GIF. A pale, white, and hairless the baby writhes fluidly against an all black background. Circling with ease and precision, a spotlight illuminates its baby-fat in delicate chiaroscuro, echoing the overhead lighting of Edison’s Black Maria studio.

The Dancing Baby came from a Character Studio’s software product sample, of a diapered human baby dancing “Cha-Cha”. It was tweaked and repurposed by software designer and then LucasArts employee, Ron Lussier into its mature viral form. The Dancing Baby’s popularity peaked in its cameo appearance on the popular 1998 Fox Television series Ally Mcbeal. The baby visited McBeal in a hallucinatory fever dream, accompanied by a cover of “Hooked on a Feeling”; the baby was scripted to serve as a metaphor for McBeal’s desire to have a child. This episode predicted, in inverse, the circuit of citation that contemporary viral culture employs: that of reiterating and recycling popular culture in a new form online.

Today, the animated GIF is 26 years young. And although its existence precedes the Internet, we find ourselves in the midst of an animated GIF renaissance: the GIF is as ubiquitous as the hyperlink or JPEG image. But if the GIF is an out of date vestige of the early Internet, why is it so interesting to contemporary audiences? Nostalgia for the 90’s cannot alone explain its popularity.

The GIF’s novelty persists by the virtue of its deficiency. Because the GIF was invented for small bandwidth networks, it cannot accurately render color or smooth shapes. This produces an image that is heavily pixelated and brightly saturated. This condensation of representation reveals the picture’s condition of being, and this revelation of its image-ness breaks our suspension of disbelief in the reality and objectivity of the image. These glitches constantly remind us of the act of looking itself. Like the fulcrum of the Zoetrope or the Kinetoscope’s viewfinder, the glitch points our awareness towards the mechanics of the apparatus: the screen and its ability to feign motion. It is the technology, not the image that serves as proxy for the act of perception itself (hence the impulse to name a genre “philosophical toys”). This simulated condition between the still and the moving, along with the technology that makes it possible, is the source of fascination with the GIF.

In relation to the presentation of “that which fascinates”, the GIF bears historical similarities to the technologies of early cinema in that it is an exhibition format arising concurrently with new technological innovations – digital computing and mechanical reproduction respectively – which because of their newness are seen as novel and interesting in and of themselves. Tom Gunning holds that early cinema operated as “a way of presenting a series of views to an audience, fascinating because of their illusory power (whether the realistic illusion of motion offered to the first audiences by Lumiere, or the magical illusion concocted by Melies), and exoticism.”

Rather then existing in service of the narrative or indulging in blind voyeurism:

“This is an exhibitionist cinema…. the recurring look at the camera by actors. This action, which is later perceived as spoiling the realistic illusion of the cinema, is here undertaken with brio, establishing contact with the audience. From comedians smirking at the camera, to the constant bowing and gesturing of the conjurors in magic films, this is a cinema that displays its visibility, willing to rupture a self enclosed fictional work for a chance to solicit the attention of the spectator (Gunning 57).”

Gunning goes on to describe “the early showmen exhibitors exerted a great deal of control over the shows they presented, actually re-editing the films they had purchased…” This remixing privileges the exhibitor over the producer and echoes the power that the blogger of today yields over mass media. The blogger appropriates scenes from pop culture to present the viewer something akin to a joke or trick. But, unlike the early cinematic innovations of the Lumiere’s Bro’s in France or the Edison Company, the GIF is not the product of well financed venture capitalists, but rather the product of the amateur.

Increasingly, the craft and production processes supporting analogue film use are being seen as antiquated and inefficient. Thirty-five millimeter film has been discontinued as the industry standard for theatrical projection and a host of technological changes are reshaping the way consumers experience the cinema. The boosters of virtual space have the tendency to dichotomize this transition from the analogue to the digital, focusing on grand narratives of progress and teleological views of innovations. This focus is on how the mediums of analogue photography and digital photography are different rather then how they are similar.

As a film artist working with 16mm and photochemical processes, my practice investigates media archeology and the history of the American West. My current series of installations entitled reAnimated GIF’s explores the innovations of Silicon Valley and the early cinematic experiments of the 19th century.

Through printing appropriated animated GIF’s onto black and white celluloid film, I am able to make physical loops out of them and with the projector displayed in the middle of the gallery, they mimic the exhibition and form of the Kinetoscope. This transposition layers the parallels and deviations in the seemingly asynchronous concepts: the materiality of 16mm film and the ephemerality of the Internet GIF.

GIF GIF GIF (reAnimated GIFS installation view) from Eric Stewart on Vimeo.

Multiple iterations of the GIF’s are projected on top of and next to each other on the wall while the projectors sit in the center of the room, like the early Kinetoscope. The projectors’ presence is hightened by the sound of the film moving through them. This sound, like the glitch or the film actors stolen glance at the camera, is likewise a revelatory stimulus calling us to the perceptual processes inherent in moving image projection– the philosophy in philosophical toys. Over time these loops degrade from the wear and tear of the projectors rollers and mechanical artifacts are inserted onto the surface of the image, where they commingle with the pixels and digital artifacts of the captured GIF.

Unlike the traditional photograph, the GIF is not a method of image capture, but instead a method of image iteration. It is a post-industrial image-making process that is inherently appropriative. Even if the source is not immediately recognizable, the GIF is a re-articulation of footage sourced from popular and viral culture in the specific form of an infinitely repeating loop. This re-iteration makes the GIF an image of a second order, and with appropriation at its core, the GIF is uniquely not quite a photograph and neither exactly a collage. It is instead a distinct hybrid which marks a deviation from both the analogue records of the past and the digital photographs of the present. The GIF is created expressly by the consumer of mainstream media for other consumers and disseminated over peer-to-peer networks. The phrase “peer to peer” is apt in describing networked connections because it refuses to acknowledge the traditional hierarchies of historical commodity networks and collapses the distinction between consumer and producer – making such concepts irrelevant.

Marcus Boon’s in his Digital Mana, describes Marcel Duchamp’s “readymades” and their relationship to industrialism and social/economic hierarchies:

“The ‘fetishized object’ in fact attains its power by being one of an infinite series and contains within it this trace of infinity. It is actually this trace of infinity, if one can speak of such a thing, which is desired and which fascinates, rather then the ‘thingness’ of the object.”

The banquet gave form to Victorian sensibilities of capital and power, while modernism manifestations were the department store, the skyscraper, and the vast expanse of the bridge. Whether agricultural or industrial, these monuments give form and order to the accumulation of capital. For Boon, it is the ready-made that reveals this rationale in miniature. For us, however, it is the GIF that can be thought of as a readymade of the Internet age, precisely because it is not an original creation of an author, but an appropriation from a network that embodies Duchamp’s readymades and the Cut-Ups and Dream Machine of Brian Gysin.

Somewhere between the still and the moving, between lowbrow kitsch and high brow experimentalism rests the GIF: a monument of immateriality and digital technology. The GIF and other new media are not, as virtual boosters would claim, the unique product of the digital era, but rather the reemergence and continuation of a form going back to 19th century entrepreneurs and 20th century experimentalists.

1 comment for “re/animating GIF’s”