by Marc Olmsted

Who could have foreseen the security camera’s Warholian static shot or robotic pan being absorbed as signifiers in commercial horror films? Michael Snow’s Wavelength could cease to make sense as a cerebral art joke in the future. Yasujiro Ozu’s Zen-like framing may evoke contemplation, but what if the image is already understood as banal and random by its viewers? Who might have imagined the repeated breaking of the “fourth wall” would cease to also break fiction’s spell as narrative “victims” now tell the audience what they fear will happen on self-recorded devices? The negative space of what is not seen on a smartphone becomes laden with chaotic potential. The far shot becomes more pregnant with meaning than the close-up in the context of a surveillance culture. It’s a world that increasingly finds more meaning in gazing at its own captured images than the direct physical experience that produced them. It’s a world where first person shooter video games not only infiltrate the narrative but further disassociate minds of some of its players in “waking life.” Even Charles Manson’s acid reprogramming becomes rivaled by virtual entertainment that can produce good soldiers or bad spree killers. In this article I will examine what tech and the awareness of tech has done to the narrative and what what we consider “reality.”

Regardless of one’s interest – whether underground or popular (or in my case, both) – it is hard for any cinephile not to be fascinated by the origins of film language. From the proscenium stage shots of Thomas Ince, he also introduced the first close-up as a novelty. D.W. Griffith cobbled together a sense of time and place and the beginnings of image as metaphor.

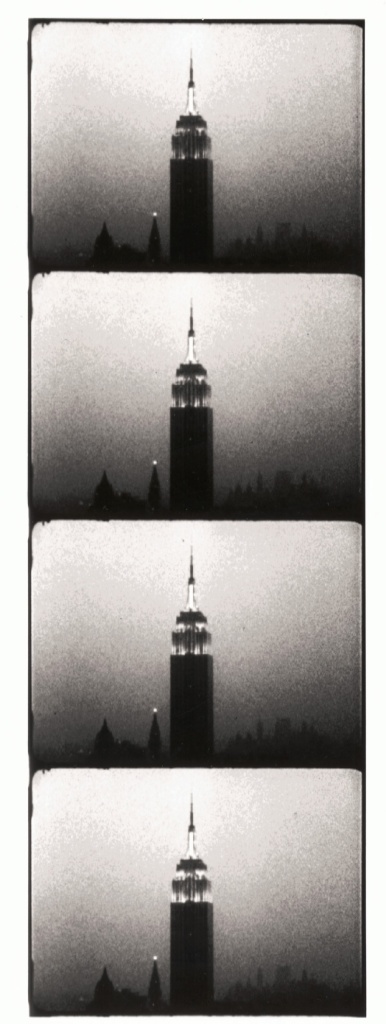

When Andy Warhol filmed the Empire State Building, he began playing with expectation and boredom. He is quoted as saying, “I like…boring things.” Whether the blank wall of the Zen student, or a static shot from the Factory, what is shared is the understanding that the boring is a mirror of one’s one mind, where art actually occurs.

Michael Snow’s Wavelength makes fun of the conventional narrative by staying in one space in “real” time, reminding us of how the entertainment of Hollywood bends experience so we are not subject to the comings and goings of our ordinary lives. In Hollywood, there is no waiting around. Ozu’s lingering shots of an empty room before and after someone enters assaulted a cardinal rule of the stage to never let that happen. But Ozu never pushed it as Warhol and Snow have.

With the advent of the cheap camcorder, the average citizen began to understand the basic syntax of what he had been formerly hypnotized by. So Hollywood sought other means to keep the money coming in – it appropriated this understanding. One of the first overt commercial examples is The Blair Witch Project, with the most iconic image being a misframed, poorly lit shot of an actress talking to the audience and telling them how scared she is. Alas, the idea is considerably better than the overall execution by directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez, with violations of its own established rules by clumsily cutting “in camera” in the same way old Hollywood would cut inside a supposedly static shot through a periscope or binoculars. It did establish the idea of “found footage” that seemed to convince some people in the same way Orson Welles’ “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast duped a small number.

George Romero turned his own attention to all manner of self-reflexive recording in his Diary of the Dead, but without the constraint that it was supposed to be “real.” Instead, it became a commentary of how such a zombie uprising would occur in our modern world – from home recording devices to security cameras. The film is a collage of these visuals within the usual narrative, both as a meditation on texture and a contemplation of such visuals as a crude extension and mutation of our nervous system – the second a worthy J.G. Ballard-like essay (itself a helpful key as to where to place Romero’s overall satire).

J.J. Abrams produced Matt Reeves’ Cloverfield and it returns to the constraints of a recording device, this time the cell phone, and the movie does stick to its own rules. It seems unnecessarily rigid, however, since only someone seeing it tripping might think that the Statue of Liberty is now gone. The CGI monster is still as obvious as stop-motion animation.

The Paranormal Activity movies (I guess there are five now, and they have already violated their own rules so thoroughly that I will only refer to the first three since I think that’s all I’ve seen – it’s kind of a big mush now) once more bring back the Blair Witch trope. Through security cameras, apparently cut together later by some enterprising outsider, we learn this strange and terrible saga of demonology (brrrr!) The first film by Oren Peli is better than Blair Witch, but not by all that much. Apparently Steven Spielberg suggested the end shot, which I won’t spoil here, but it may literally have made the film the hit it was (psst…it opens the trailer to Paranormal Activity 2).

By the second film, the director/writer had been replaced by Tod Williams, and the Michael Snow references (intentional? hard to say…) begin showing themselves. There are prolonged night shots of the the outside pool where a buoy floats. NOTHING happens. Yet the audience brings an enormous amount of dread to these images. It does require that you see the first one, apparently, as my wife just thought they were boring. That alone is interesting enough for me to write an article. The signifier had changed if you saw the first film.

By the third film in the series, another new director team (Henry Joost/Ariel Schulman) has the hero (male, natch) strap a security camera to a slowly back-and-forth turning of a plug-in fan in the living room (living? – not for long). Now we are in Snow country for sure. Back-and-Forth, or <—> as it is more correctly titled does this with a camera catching each side of a room of its extreme repetitive pan. (Of course, Snow, in the course of 50 minutes, begins to pan so fast that we see a stationary optical illusion – that doesn’t happen here.) Since modern directors are almost invariably film students, exposure to such films is highly likely. As further evidence, John Mayburry’s The Jacket (a sci fi time travel movie, the plot a sort of straightjacket La Jetée) ends with a shot that so resembles Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight, I waited to see it credited in the end titles. It wasn’t. In fact, this duplication of bits of dessicated moths taped to film stock turned out to be an “homage” by Mayburry, as I later tracked down in an interview.

This panning shot has the same dread-laden significance to an Paranormal innoculated audience. All the way to the left, nothing happens. All the way to the right, nothing happens. Over and over. Then finally, there’s some de-emphasized shadow. What’s especially weird is that we almost return to the origins of film with this completely stripped down language. No cutting, not close-up. No reaction shot. We are the reaction shot. The ads for the film become green night vision audience reactions.

The climax involves a security camera set in a bird’s eye surveillance cranny. The signifier of surveillance, distance and unclear image at a high angle, becomes its own syntax. It now suggests “reality,” even as it gives less satisfying information to us. Suspense is created by not being fully aware when something has changed in the shot until it is…oh no, too late!

I’ve seen the trailer for the fifth Paranormal Activity, and is obvious that to introduce something new, there has to be a camera that can record psychic phenomena. This is so fake and obvious even in the trailer (it looks like every cheap horror film effect since the invention of CGI), it would appear the franchise is finished. Some executive just didn’t get you can’t do that. The way Blair Witch or Paranormal Activity films work is that we already possess the means to record. If we can do it, it must be real. Right?

Movie clips: