by Gerry Fialka and Will Nediger

“But that a man in chains should shut his eyes, the world would explode.” – Octavio Paz

“But that the white eyelid of the screen reflect its proper light, the Universe would go up in flames.” – Luis Bunuel

Samuel Beckett’s Film, his only cinematic work, as well as the only film of the renowned theater director Alan Schneider, is concerned with the more sinister aspects of the camera eye. In it, an eyepatch-clad Buster Keaton is pursued by the camera (referred to in Beckett’s script simply as “E,” for eye) and tries in vain to escape its gaze.

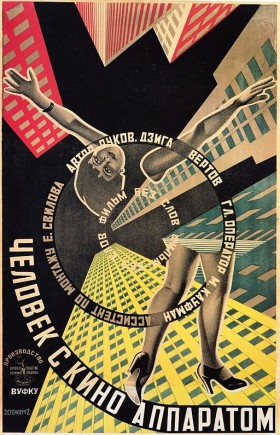

Ross Lipman’s adroit “experimental documentary” Notfilm dives deeply into the creation of Film. Though it includes its fair share of interviews, it’s not a typical talking-heads documentary. Lipman transcends the “essay film” genre with keen wit, stimulating new questions about the “fake fake” documentary form. He makes liberal use of clips from other films: Notfilm mashes and messes with moving image explosions, even sneaking in “Structural” cinema. He includes a pseudo-flicker film evoking the stroboscopic films of Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits. Lipman acts as a cinematic alchemist, interweaving clips from Keaton’s early two-reeler comedies with clips from Man With The Movie Camera by Dziga Vertov, whose brother, the cinematographer Boris Kaufman, worked on Film. In this way, Lipman creates a tertium quid (an unidentified third element caused by combining two known elements) from the raw material of film. He identifies Notfilm as a “kino-essay” which describes this third element.

In a reference to the close-up on an eye at the beginning of Film, Lipman includes the classic eye-slitting scene from Un Chien Andalou. Tellingly, he doesn’t show the entire clip, with liquid oozing out of the dead animal’s slit eyeball (which many viewers have assumed is a real human eyeball being slit). Why deny us the punch line? Notfilm is like Film itself, filled with jokes on the audience and hidden aspects the viewer must fill in. Film, after all, stars Buster Keaton, he of the iconic “Great Stone Face,” but his face is not even shown on screen until the end of the film.

Indeed, as Notfilm shows us, Keaton and Beckett make an odd pairing. Keaton once said “I don’t act anyway. The stuff is all injected as we go along. My pictures are made without script or written directions of any kind.” Beckett’s script for Film, on the other hand, reveals an enormously detailed vision. But, as Amos Vogel wrote in his book Film As A Subversive Art, “Words are not the best way to deal with a visual medium.” In the end, the finished product fell short of Beckett’s vision. Neither Beckett nor Schneider had made a film before, and they hardly consulted Keaton, who had decades of experience in film making. Maybe for that reason, Film has long been considered an interesting failure by most critics, and even by Beckett himself. But to quote Beckett: “Ever tried? Ever failed? No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” In a way, Beckett’s entire oeuvre is about the impossibility of success. If words can never truly capture a visual medium like film, then a film can never truly capture its creator’s vision; all you can do is fail better. Beckett never wrote another film, but perhaps he knew that one day, Lipman would “fail better” by creating this astonishing hybrid documentary.

Milestone (http://www.milestonefilms.com/) plans a DVD/BluRay release before the end of 2016, with a wealth of extras.

Gerry Fialka and Will Nediger are currently writing a book on the future of the history of avant-garde film.