by Mike Mosher

Inspired by a book, this is going to be a sentimental journey, where I tip my hat to great ladies once near, and some far away, yet who memorably caressed me with print and cinema. Beyond my own scattershot appreciation of glowing Jewish women I once knew out West, I want to load aboard Renata Adler’s novel, Speedboat, three others, on another coast, involved in cinema: Pauline Kael, Susan Sontag, and Maya Deren.

In high school, my mother was horrified at the prospect of me dating Jewish women, and horrified when people thought our family was Jewish. To great comedic effect, the family of Ascher Moser—the name, different from ours, by a single letter—moved into the house next door, and my mom, through gritted teeth, fielded calls inviting her to join the Synagogue or women’s Israel-support organization Hadassah. Like Gregor Rezzori, who wrote, of several Jewish women central to his life in his ironically-titled Memoirs of an Anti-Semite (and, like Renata Adler’s writing, republished by New York Review Books), I’m unable to tell how much of the appeal of those women I knew was lust for the forbidden Other, and how much it was genuine admiration and passionate affection for their own individual virtues of intelligence, wide reading, artistic skills, shared political commitments, urbanity and urbane sophistication, now remembered fondly.

I like to believe it is primarily all about the latter virtues, the fact thatI was drawn to them. Many such Mission District women in the early 1980s were creative radical activists and many, as it turns out, were Jewish: active in the Mission’s anti-gentrification movement (yes, even 34 years ago), and participants in marches, street theater and other cultural projects against US intervention to support dictators in Central America, or by making murals to support the independent Polish workers’ movement, or local community arts. Their political work was important to the history of the City, and should be studied in greater depth. Among the women I met and cavorted with–with plenty of wine– one was ex-girlfriend of one of my favorite college professors. (It was as if his recommendation sped up the process of our coupling.) And another I met the first week of a new semester in graduate Painting study at San Francisco State. I think the beach front fog rolling on to campus makes bodies seek warm bodies). Another of these women friends turned me on to Walter Benjamin, loaned me albums by X and Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, and was an anti-gentrification “billboard correctionist”, culture jamming advertising slogans in the night air to make statements which would encourage ordinary people to rethink their lives. Much as Detroit rock critic Lester Bangs proclaimed “The ‘60s ended in 1973”, maybe I should consider the 1970s over and done with when I settled down in 1983 with my now wife.

But in the 1970s, the theories of cinéastes and Directors in France had influenced American universities to offer Film Studies, affirming film as a creative [independently funded] art form. This is the milieu that nurtured much of the San Francisco experimental scene, as well as other contributor’s like me such as Gerry Fialka. Fialka was greatly influenced by experimental film screened at the Ann Arbor Film Festival (AAFF), which in 1962, sprang from the long-running University of Michigan’s Cinema Guild, upon the inspiration of artist George Manupelli. There were weeks in my teenage years growing up in Michigan that I saw a film a night; rarely a first-run Hollywood production, and rarely in a traditional movie theater!

As a student at Dartmouth College I was on the Film Society board, studied with Director Joseph Losey, continued Super 8mm projects, caught foreign, innovative and eccentric new movies with friends in Boston, Cambridge and Manhattan. I occasionally found copies of the Sunday New York Times in the college’s Hopkins Center for the Arts, on quiet Sunday afternoons when I’d gone up there to noodle around on a fine grand piano the library owned. Unlike many of my classmates from the East Coast, the Times wasn’t often found in my household growing up. I remember reading Pauline Kael’s long New Yorker piece, later published as a best-selling book, about Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and screenwriter Joseph Manckiewicz’s under-appreciated role in the film’s success. Her article propelled that movie into the canon and the misused, misunderstood director (then alive, obese and appearing in wine commercials) into critical Valhalla.

Kael was a prominent New York film critic, though this Midwestern boy was skeptical of east coast media hegemonies telling us what to think. She championed Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 as harbinger of a new spirit in Hollywood following an era of irrelevant doldrums, the multi-vocal Nashville, and the sexually and emotionally frank Last Tango in Paris. She panned Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, claiming it was lauded for its interrogation of the Holocaust rather than any aesthetic strength, and this angered many.

Renata Adler and Pauline Kael were supposedly bitter rivals in New York. Adler’s review of Kael’s 1980 collection of film reviews When the Lights Go Down sneered:

“… it is, to my surprise…jarringly, piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless… an entirely new style of ad hominem brutality and intimidation… little more than an attempt, with an odd variant of flak advertising copy, to coerce, actually to force numb acquiescence, in the laying down of a remarkably trivial and authoritarian party line.”

But, Adler also reviewed European films; Buñuel’s Belle de Jour (1967) and Godard’s Weekend (1968). Her praise of the 1968 Yellow Submarine, “an animated meandering journey filled with puns and dry British humor, where psychedelic music videos take precedent over any linear story” now seems like a possible blueprint for her own upcoming fiction.

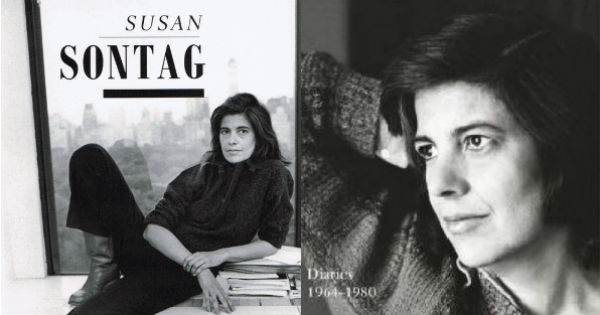

As a critic, Susan Sontag was edgier, her Warhol- and Jack Smlth-appreciating Notes On Camp establishing her reputation in the 1960s. In 1975 Losey reprinted for us Sontag’s “Fascinating Fascism”, the New York Review essay where she noted how the 1970s books of Leni Riefenstahl’s photographs of elegant African men had an aesthetic not all that different from the strength-, macho- and beauty-loving aesthetics behind Olympia, the 1936 Olympics documentary, when Riefenstahl was Adolf Hitler’s favorite Director. The essay later appeared in Sontag’s 1981 collection Under the Sign of Saturn, and this book’s title essay is Sontag’s long mash note to cinema enthusiast Walter Benjamin, who died in Europe when young American Sontag was five years old.

It was a Japanese girlfriend of mine, not a Jewish one, a Photography grad student, who gave me copies of Sontag’s (sadly, limp and un-engaging) fiction when she found them remaindered at a bookstore out in San Francisco’s avenues near where she lived. This same woman also accompanied me to the seven-hour showing of Hans-Jurgen Syberberg’s Our Hitler at the York Theatre repertory cinema. An appreciation of that film appears in Under the Sign of Saturn.

Author Photos

In the author photos on some of her book jackets, Sontag, in a turtleneck sweater, jeans and boots, gazed challengingly at the reader, incredibly intelligent and incredibly sexy. Though Susan Sontag had a lifelong attraction to women, and her Notes on Camp proved affection for or attention to one tragicomic gay aesthetic, her lesbianism was not generally known or publicized to the general public. In San Francisco’s Mission I lived half a block from a notable women’s bar Amelia’s, on Valencia Street (title of a book of lesbian punk adventures by Michelle Tea, 1999) and when I first came to S.F. and walked around its fascinating neighborhoods at all hours, returning home one night I glimpsed hulking figures on motorcycles massed outside a bar several blocks ahead. Thinking it too obvious if I crossed the street, I hoped the bikers wouldn’t hurl a beer can or punch at me as I walked by. I was relieved to find the behemoths were women, all of whom could’ve kicked my butt had I harassed them. But, I find such women are generally less driven by macho to pick a needless fight.

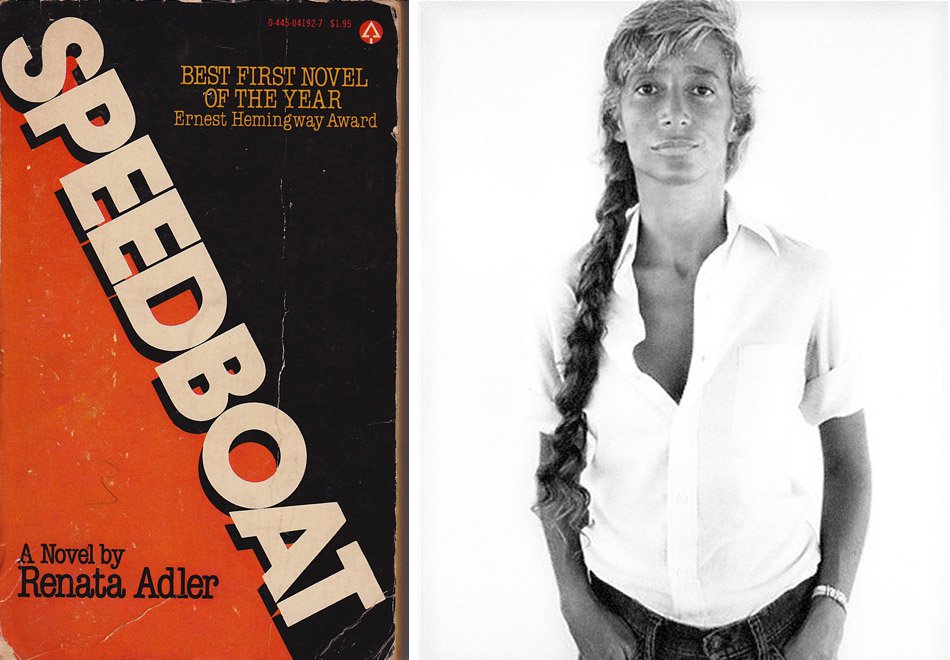

Until Adler’s Speedboat, I don’t believe I’ve ever before bought and read a book because the author’s photo on the back of the book looked, well, hot. I had read appreciative reviews upon the republication of her two novels Speedboat and Pitch Dark that praised her literary style. Bookforum’s review of the books also reproduced full page another photo of her from the 1970s by Richard Avedon, standing with a white shirt unbuttoned seductively just enough [to see some chest] which also stuck in my mind.

Films of the 1970s

Some films of the 1970s, shown in colleges in classes or festivals, were fast-moving and visually abstract, moving light and color and sound. Some were narrative in free-wheeling, ad hoc, innovatively humorous kinds of ways, like those of Jack Smith in New York, George Manupelli or San Francisco’s George Kuchar.Others were weirdly affect-less, whether products of Hollywood’s buckskin-fringed edge like Who is Harry Kellerman? or Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie. American students regularly consumed European offerings, like Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970s movies, despite the longeurs of The Passenger, or his earlier Zabriskie Point (spoiler alert: everything blows up at the end in slo-mo, over Pink Floyd’s “Careful With that Ax, Eugene”).

Adler’s novel (if it is truly that, and not merely a diary with names changed upon a lawyer’s insistence) Speedboat has a similar lack of affect, and stoned, let’s-just-see-what-happens feel and pace to it. Its short, episodic segments, someplace between epiphanies and mere reportage and description of a moment, are like short movie scenes, cutting from one place and time to another. Yet for this reader, they never cohere into a narrative arc; never lead up to something happening that we really care about.

The story line goes: A women breaks her back in a seemingly thoughtless speedboat accident in Italy on what was supposed to be a pleasurable outing, though she evidently gets medical attention promptly, gets flown back to the US, is presumably OK for we never hear of her again. The narrator has several different men appearing in her life, apartment or hotel, showing up in the night and staying for breakfast, but the only clue to any significant physical passion is when she’s living overseas with one and Italian village women, hearing her vomiting from food poisoning, assume she’s pregnant and say “Maybe now he’ll marry you.” Parties are attended, children make seemingly prescient comments, and quotidian events take place on New York streets or in offices. A lot of little things happen, all over the place, to all sorts of people, in between. BFD.

The Talking Heads sang in New York, and David Byrne depicted in his movie True Stories, people leading supposedly normal lives which, when observed or commented upon, prove slightly weird and humorous, but Speedboat’s Renata Adler doesn’t really conjure up characters, only puzzlement. On second reading the book proved just as formless. I contrast it with the equally observant but more meaning-finding Joan Didion essays from the sixties, seventies, eighties, like Waiting for Morrison about grim rock band The Doors, the report prominent in my (and everybody’s) parents’ LIFE magazine, to later appear in her collection The White Album. Didion’s essays on the brutality of the war in Central America that became Salvador inspired my 1983 graduate show in Painting at San Francisco State.

Adler’s Writing, Deren’s Editing, and Pulpy Sexy Fiction

On my third reading of Speedboat that I began to appreciate it. The first 27-page chapter “Castling” appeared to have many small, short “scenes”, little cinematic set pieces: the diner-revelers, from the restaurant with the rat to the late-night streets; offices; summer camp in adolescence; colleges and apartments; then it all circles around to New York restaurants.

Might Adler’s fiction be compared to Maya Deren’s cinema? Deren, born Eleanora Derenkowskaia in the Ukraine to a family that fled its anti-semitism for Syracuse, NY, is quite ready to employ jump cuts between shots, create a rhythm that is not like the mainstream narrative movies of her day, but with Deren we don’t wonder what the subject matter is. While they might be multi-directional, purposely disorienting in movement and trajectory, in the dream imagery of Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) or dance leaps in A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945) Deren’s scenes don’t contradict each other, or diffuse a central point, as Adler’s tend to do on first reading. The millennial might comment OMG on Deren films, but WTF on Adler’s fiction.

Richard Avedon’s author photo for Speedboat, in (California? Long Island?) sunlight, with shadow licking the top of Adler’s nose and cheeks like a minor sunburn, caught and held my attention. I gazed at it, her self-contained, challenging expression as if I’d approached her sitting on a bar stool, the sunlight bounced up so the tops of her cheek, center of her nose in shadow, much like a photo a girl I had a painful crush upon in college sent to me from London of herself. I felt the mingling of literary and sensual pleasure probably much like that experienced by the female buyer of a 1990s bodice-ripping romance novel whose cover might have featured the buffed and shirtless male model Fabio. I don’t, to my knowledge, really know any woman who buys those Harlequin Romances, though the older sister (Diana Autin) of junior high heartthrob wrote some, I discovered. I read Jackie Collins’ Rock Star though I don’t remember any of it, but I guess that’s an entirely different genre. If I purchased Speedboat and read it in a fog of nostalgia—nostalgia for the cinema culture of the 1970s and early 1980s, for the San Francisco Mission back then, and for those intellectual Jewish women I dated there—my exasperation with its lack of sexiness here echoes that feeling I had when I was disappointed after reading Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids, of her days in Manhattan with roommate Robert Mapplethorpe.

Last Words on Renata

Somehow I had thought Renata Adler had died young, which only added to the romance of her myth. Adler is now in her seventies, enjoying the new interest in her work. I’ve since seen pictures of the author at the book’s 2006 reissue, a distinguished woman with a long silver braid of hair. In 2014, New York Review Books reprinted her journalism in a collection After the Tall Timber: Collected Nonfiction. The Speedboat paperback’s cover features a painting by abstract expressionist Helen Frankenthaler, whom I remember in Emile de Antonio’s 1970 documentary Painters Painting, well-dressed and pushing around dilute colors with a broom on large canvas on the floor while drinking cognac from a brandy snifter. Perhaps this may be a metaphor for Adler’s cool, detached and intuitive writing process too.

If I read this book under a bullheaded boyish misunderstanding; I wonder what engages readers of today with Renata Adler work, especially a new generation of female readers, besides perhaps the dispassionate observation and notation of urban life around her. Not Baudelaire, not Benjamin’s flaneur, but the role model of an equally independent flaneuse, is this Adler? When I bought Speedboat in Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor, the student-age woman at the cash register said “Oh, I love her, she’s so great!”, and another independent bookstore there called Nicola’s featured a long, impassioned hand-written staff recommendation beneath their display of this book. So approach and board Renata Adler’s Speedboat as you will, freighted with your expectations, or not.

Other reviews: