Jack Sargeant. Against Control. (Goteberg, Sweden: Eight Millimetres, 2015)

When a prominent cultural figure ceases operations on the mortal plane it is customary for them to relinquish earthly management of the artefacts that are attributed to them. The implications of this custom vary and are most significantly contingent on the prominence and position of the oeuvre in relation to the attentions of the various Reactionary Forces. Most simply, a “problematic” figure may be totally occluded, a relatively straightforward process where the figure’s prominence was originally sponsored by the self-same establishment. In other cases, where perhaps the figure has a significant clientele composed of autonomous individuals, the work may need to be repositioned via a process of selective emphasis, which may be achieved via the market, the academy, or a combination of factors, some of which I haven’t thought of yet.

William Burroughs was still alive when I first met Jack Sargeant, Brighton (UK), 1980s. Wherever Burroughs’ name surfaced in those days one of the main topics of discussion was the author’s ongoing mortality, which struck us as especially anomalous in those days when heroin and homosexuality were the preferred Official Folk Devils (conflated and promoted via the AIDS “epidemic” that was prominently visible there and then). Burroughs fans would often lay odds as to what we thought would happen to his work posthumously. The odds-on favourite was attempted (but probably failing) total occlusion, since at that stage Burroughs was merely an underground superstar and we had reckoned without future endorsements from Nirvana, U2 or Nike Corp. Looking back from where we are “now”, it’s hard to know exactly what the fuck happened when Burroughs eventually threw his six. Sure, the industry could easily shove him into the Pantheon with his novels branded as legitimate classics and widely taught in the academy, but something else went on in parallel, apparently unsponsored and largely autonomous. By the time of his death, Burroughs’ fans had founded a lively cottage industry in critical spin-offs. Burroughs himself had laid the theoretical groundwork for some of this in his own relations to the 1960s London underground, the late seventies punksplosion and post-punk industrial culture (which did not even have an overground analogue at that time). Here we should pause to salute James Grauerholz (Burroughs’ agent/manager) for his visionary application of Burroughs’ viral theories at a time when open source and free software philosophies were the province of a very select few.

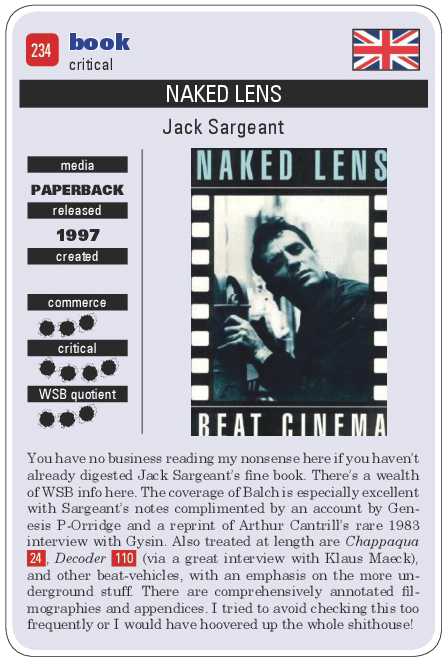

Probably the bestselling, in the UK at least, of these self-generated volumes was Jack Sargeant’s Naked Lens: Beat Cinema (London: Creation Books, 1997), which is still in print almost twenty years on. By the time of Burroughs’ centenary (2014) there was a veritable explosion of autonomous tomes, not discounting my own Even the Old Dude is Cool: William S. Burroughs on the Wheels of Steel and the Silver Screen (Ecclesfield: LedaTape Org, 2014) which I shall not mention further for fear of appearing gauche.

So now we have Jack’s new Burroughs book, a 100 page hardback from Eightmillimetre Press, based in Goteberg (Sweden). It’s a compilation of essays on aspects of Burroughs’ work written over the last five years or so, reworked, updated or expanded, for book publication. It comes complete with a short introduction by Michael Spann, whose own book William S. Burroughs’ Unforgettable Characters: Lola “La Chata” & Bernabé Jurado (Providence: Inkblot Publications, 2013), dealing with Burroughs’ Mexican years, is highly recommended.

Jack kicks off his book with “Fifty Years of Naked Lunch”, which elaborates the circumstances around the origination of WSB’s breakthrough novel. Obviously, most committed Burroughs fans will be familiar with at least some of this subject matter, but the piece succinctly pulls together the most salient aspects for a general audience. It betrays its origins as the text of a public lecture to the extent that Jack’s voice is almost audible in the writing, but this merely enhances its appeal for those who may already be acquainted.

Two pieces for Fortean Times follow on. “FT” is a phenomenally popular British monthly specialising in anomalous phenomena, and it would amaze me if WSB himself had not been an avid reader. The first piece is an introduction to the Dreamachine, a flicker machine for inducing altered states of consciousness. Drawing on Paul Cecil’s 1996 book Flickers: of the Dreamachine (Hove: CodeX, 1996), Jack’s short essay manages to pack in all the essential and interesting info. The other FT article is on Joujouka music, an ancient form native to the so-named village in the Ahl Srif mountains of northern Morocco. This music has a fascinating back story and is intimately tied to the development of the Dreamachine.

It’s very gratifying to have Jack’s essential piece from The Wire on Burroughs’ recording career here in book form, especially in this expanded version. This is out-and-out the best overview to this vast, often obscure, field. In the interests of full disclosure, I will here volunteer my sole trivial whinge about the book, in that the article is, forgivably, designed to be read as a piece and could have been better formatted to facilitate reference use.

The final essay in the book provides background on Burroughs’ own pantheon of mythological outlaw heroes. Given the short length of the piece, and the fact that it was drawn from a lecture, it would be unrealistic to expect more than a general overview of a theme that obviously awaits an imminent volume of its own. This brevity then comes as a relief as any (conventional) book-length work would necessarily assume its own self-interested political perspective.

Jack’s book joins a select few in the Burroughs canon that eschew the sensationalist aspects of his life that were principally the fruit of his actions. Here Jack focuses on the “secondary” characteristics of Burroughs’ oeuvre, drawing on his pre-occupations. The worn-out old balance of considered opinion barely rates a mention. This is especially pleasing to those of us who try to keep up with the Burroughs industry, of which Jack is erudite to the extent that his book offers new insights to even the most seasoned observer. The whole shebang is presented in a style that is so accessible it feels like you’re mainlining pure Burroughs facts direct in the cortex. Notwithstanding this, it’s probably fair to say that the book will offer most to the reader who is keen to investigate the substance of the oeuvre, or who wants the background to more fully understand terms and theories of Burroughs’ work. In this sense Against Control is effectively the polar opposite artefact to Cronenberg’s abysmal filmic effort that we shall not dignify by naming here. I can think no greater endorsement than that.

Strong

14 Feb 2014

—————–

Simon Strong is the North England co-ordinator for The LedaTape Organisation, and based in Melbourne, Australia. He is the author of several books including Even the Old Dude is Cool: William S. Burroughs on the Wheels of Steel and the Silver Screen. His new book, Unquiet Dreams: The Bestiary of Walerian Borowczyk is due imminently. A selection of his experimental films, including his WSB-inspired The The Naked Lunch and the Naked The Naked Lunch, are available via ubu.com.

http://www.ledatape.net/?author=Simon%20Strong

http://ubu.com/film/strong.html

—————————————-