by Shelby Shaw

I began working in the film industry while studying film and video at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, renowned for its conceptual approach to art. In this way I was receiving both a DIY-underground and a mainstream understanding of what makes a film successful. When I moved back to Manhattan I was invited to interview just about everywhere my resume went: to distributors, producers, and sales companies alike. However, I was quickly unsettled by how perplexed each interviewer nearly always was when they would look at my CV and ask, “So why did you go to an art school to study film?” I wasn’t interested in the bloated egos of film school programs that churned out blockbuster-dreaming production crews. I went to an art school to learn art and I supplemented that education by interning with the art house film business on the side. The more I worked in film (sets, editing, corporate cubicles, red carpets) the more I felt I knew too much. I now find it hard to watch films without feeling conscious about how they are made for “general audience interest.” I much prefer, instead, idea-driven modes of video art which answer to no authorities and ultimately need to please no one. There is no [official] industry for experimental and avant-garde moving images; they are trials and appreciations, tests and decision-making processes. They are neither blockbusters nor bankruptcy flops. Experimental films are imperfect but, that’s why I find them so comforting.

A film is a unique record of committing an image to movement, even if static. Yet a movie is a unique construct of film which decades of improvised, then corporatized, Hollywood business models have committed to a rubric of narrow expectations for profit and entertainment, with little margin for error or bending the rules. The film business is an industry, and as with any industrial capital, the cogs work for the machine to produce the tried-and-true results that millions of box-office dollars can’t dispute economically.

But how is it that an art form has come to be committed to so many production constraints in the name of value?

The idea behind making a film, if you want it to make money, is to get picked up for distribution theatrically, on-demand, and sold through a retailer. Most features will try to run the festival circuit where distributors hungrily scour the screenings and negotiate deals while trying to avoid buying anything that ends up with a flop review. Sales agents will attend festivals to conduct business as usual selling titles to whole territories: the Middle East, South America, India, North America, Europe, etcetera. The films on the table are typically not finished, and sometimes not even shooting yet. When one major studio film from a popular adventure franchise with a young female lead, was up for sale at Cannes while still in pre-production, the distributor was showing crudely-animated footage of what one scene “would” look like, as a way to tease out sales. The budget for this film was $175 million and it would not be ready for release for another two years. Some territories, such as the Middle East, may require an amendment as part of a negotiated sale, like recutting an entire movie to adhere to censorship laws. Do not waste a territory’s time during sales, such as showing films with children protagonists to Japan where this is considered an unpopular trope and will not sell, according to business.

Anthology Film Archives remains an iconic Manhattan venue for new films and artists, but especially as a reliable space to screen historical and unsung experimental films and video artworks.

Rather than give their audiences unbound options, film sales agents and distributors tailor the choices in order to remove what they believe the people would not be interested in seeing, although sometimes a less-than-promising film that can be bought cheaply can be used as filler for quota. Box office numbers are reported for every week a film is playing at a theater, largely through theaters inputting their ticket sales into software or – as some prefer – calling or writing-in the numbers directly. Only the opening weekend numbers will determine whether a film was an economic success or a flop, though. What posits mainstream films as financial success stories is that they are a feedback loop between audience and options: what plays at the theater is what the people will pay to see, and the people will pay to see what is at the theater. Replace will with can and effectively the idea of rights turn to privilege.

The dog chasing its own tail is harmless in its passivity to not consider what is really happening.

Black and white films are considered risky to buy for the same reasons as subtitled films: the general (American) population is believed to be disinterested in putting forth an effort to comprehend, either by having to imagine color palettes or reading dialogue lines. A cast with no “big names” in it can be a red flag to investors, who don’t want to take a chance on supporting people who have not been proven to be audience favorites. For major films working with talent agencies, sometimes a package deal is setup in which the agency can provide an assortment of actors for various roles (Motion Picture Talent), and/or a director and screenwriter (Motion Picture Literary Talent). These package deals are unique to the agency’s client list, thereby limiting who can be considered for a film by barring the production from employing an unsigned talent or one signed to another agency. The choice to employ the best talents for a project becomes a political preference of which mediators you want to retain closely in your network.

The desk of an assistant for a half-dozen clients at one of the top-renowned talent agencies, located in Manhattan.

Once a film is picked up, the distributor handles marketing and advertising, publicity, and theatrical release dates. On-demand viewing services limit a film’s release: if a major on-demand network buys a film, they are the exclusive provider for the duration of the contract, which is why you would not be able to find that title simultaneously listed on, say, Netflix – until the network’s contract ends. Because of the popularity of on-demand viewing providers, a distributor may seek to change a film’s title from beginning with a letter towards the end of the alphabet to instead beginning towards the front of the alphabet so it appears at the top of a search field. Similarly, a title may be changed to fit within the character count of certain TV and on-demand platforms.

Publicists will pull press breaks wherever a film is mentioned, in any language, with a starred review, rated review, and don’t forget to sum up the tone. What’s a good quote to pull for a poster or the DVD cover? Whose byline is most popular that can be flashed in a press release? Consider the raves quoted on an ad for a film, and take note of how many are quoted in full sentences. Does it sound full of passionate awe for yet another masterpiece? Go find the source review and read the whole thing. A film needs only a few positive adjectives for good publicity, and an ellipsis will always be at home in a press quote. For critics attending every screening they can schedule, trying to get their opinion out first without being tainted by other critics’ voices, and trying to be quoted by a distributor across marketing materials, it can become difficult to weigh-in on when to spend or spare another word synonymous with good.

Press is an illusion of sincerity yielding respect.

Released in 2015, “Joy” is a fictionalized telling of Joy Mangano, who designed a self-wringing mop in 1990 and became wildly successful thanks to QVC airtime. Poster courtesy of 20th Century Fox.

If you think this is all handled by seasoned veterans of unbiased merit, don’t forget the departmental interns. One major Manhattan-based film marketing internship paid a $10-a-day stipend, where across the street the popular lunch spot sold salads for $12. Another major Manhattan film business paid hourly for a full-time internship in distribution, but at minimum wage with no overtime, no benefits, and no opportunity to stay on after the initial few months were up; later the corporate policy effected that interns must be current college students or within a year of having graduated. Other distributors, marketers, agencies, production companies, and festivals are often all-too-happy to offer an opportunity without pay, sometimes for school credit, but rarely do they have a coveted job to offer at the end of the tunnel.

It can be easy to make “a movie” as we understand it from consumerism’s perspective: audiences recognize the pacing of a film trailer, the glossy aesthetic of a high-definition camera, and the credit block at the bottom of a film poster or back of a DVD. These are details that signal a “legitimate” film. If it’s audience acceptance you’re after, or an audience at all, the key is to unpack the release strategies you are confronted with daily and begin to master the art of mimicry. The advertising has become uniform across subway ads, the sides of buses, highway billboards, and flipping through a magazine. Print ads are uniquely all the same and all failures: they showcase the most popular cast names and whichever recognizable actor is involved.

Did you know what Joy was about just by seeing the poster?

Alternative spaces, such as artist and activist collective The Sunview Luncheonette in Brooklyn, turn into DIY-programmed venues for screening series, video premieres, and general sharing of works new and old, found and original.

Video art and experimental films can become an acceptably finished piece with no middlemen. Whether shot on tape, digitally, or on physical film, artists’ moving image works are drastically less involved with business and less controlled by economic or social expectations than theatrically released films seeking distribution and profit. Art films can make money, as there are distributors who specifically work in this realm, but the difference between video art and a “feature movie” – whether a blockbuster studio franchise or debut indie trial – lies heavily in the art piece’s not needing to meet any requirements assumed by an audience. This includes, but is not limited to: not needing a plot, a script, a star-studded cast, the backing of a producer, or special effects.

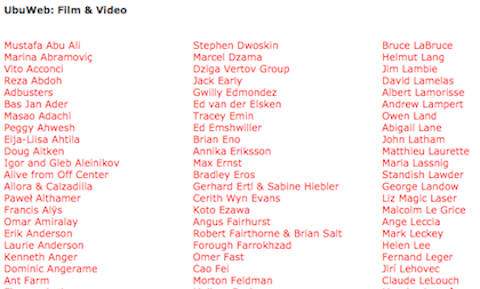

The most notable difference, and perhaps the most disheartening truth, is that video art and experimental films have fewer opportunities for exhibition. While art house distributors exist around the world (Electronic Arts Intermix in NYC, Re:Voir in Paris, LUX in London – to name only a few), a video artist may need to rely on a gallery’s representation (which would lead to being constrained to a gallery’s schedule of when and how a show goes up) or self-booking smaller theaters, which can be an expensive risk.

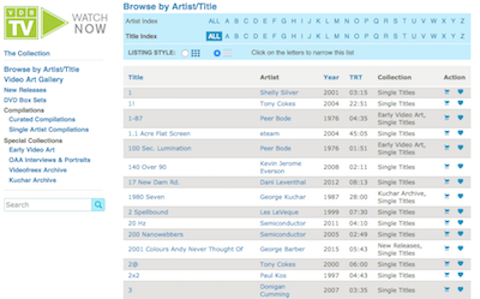

While some platforms exist online for anyone to view artists’ works (e.g., Ubu, Vimeo, Acre TV, ESP TV, Network Awesome), and even invite-only hosts that rely on user uploads of lesser-known and undistributed content (e.g., Karagarga), a curious person without this knowledge may be unable to gain access to a viewing link or public screening room. There is no Netflix, Amazon, Hulu, or other major online service specifically for on-demand video art. But this does not mean there is no demand for viewing video art.

The moving image is becoming a private artwork turned to chance encounter.

Video Data Bank, in Chicago, distributes artists’ moving image works and has small public-access screening rooms that can be reserved for in-house viewing.

Video art does not need a shooting script. It does not need to send revision after revision to the producers for approval. It does not need a story line or narrative arc. It does not need a talent package to sell box office tickets. It does not need to fit into any expectations, can be wholly explicit, or terribly tedious.

The rubric for art is what it isn’t on the other side of the spectrum, in the cage built of industry and regurgitating mimicry. To make the best machine, we must first update the cogs.

this is a really good rundown of the “machine” we as viewers inevitably subsist to. in this context it would be interesting to see how the algorithms or filtration of choice in online streaming (netflix, amazon prime, etc.) have changed over time, in which ways have they been channeled and for what purpose?