The Art of Insolence

24 Sep 2008

Despite her varied accomplishments, it seems Nelly Kaplan remains largely unknown outside of France. No one has yet published a book-length account of her life in English; the few scholars who have written about Kaplan aren't even in agreement about the date of her birth! Wikipedia acknowledges that she exists but offers no information about her career, which has now lasted for more than half a century. You'll find her filmography on imdb.com, but don't bother looking up Kaplan at your local library: books like Manuell's International Encyclopedia of Film, Boussinot's L'Encyclopedie Du Cinema, and Cawkwell and Smith's World Encyclopedia of the Film all fail to mention her.

...Surrealist female filmmakers? There's an extremely short list, and Kaplan's possibly the only one on it who's ever made feature-length work (depending, perhaps, on whether Lena Wertmuller makes the cut). So, let's see, shouldn't Nelly Kaplan's name come up somewhere in Barbara Quart's Women Directors, E. Ann Kaplan's Women and Film, Rudolf Kuenzil's Dada and Surrealist Film, or Linda William's Figures of Desire? Somehow she is absent from these as well. English-speaking film scholars basically have two good options if they're looking for recent books that recognize Kaplan's significance: Michael Richardson's Surrealism and Cinema, and Penelope Rosemont's Surrealist Women. Rosemont's book contains some of Kaplan's essays (including one previously reprinted in Paul Hammond's The Shadow and its Shadow), excerpts from fictional work, and a short interview. Richardson's on the other hand spends a chapter fully scrutinizing Kaplan's Surrealist credentials while exploring the theme of "sexual revenge" evident in much of the filmmaker's work. Aside from these admirable efforts, the pickings are slim: you might dig up a couple overview essays (most notably Chris Holmlund's and Lenuta Giuki's), some scholarly reviews of some of her individual works (eg. Beverle Houston's 1979 piece in Film Quarterly) and a few scattered lines in various books (Annette Kuhn's Women's Pictures, Kevin Brownlow's Napoleon).

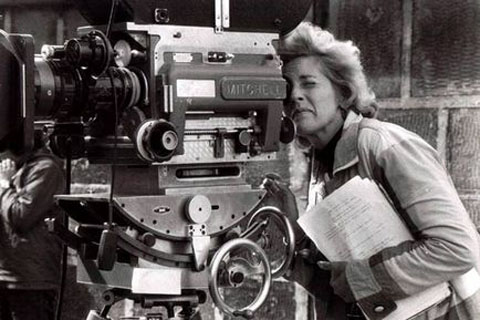

While Kaplan's greatest commercial success has been as a screenwriter for French TV movies such as Les Mouettes (1991) and Polly West Est de Retour (1993), her uniqueness and importance is more evident in what she's accomplished in the margins and the shadows of a (historically male-dominated) motion picture industry. Her own films, those few for which she has been able to find funding, have been variously misread, wrongly marketed, banned (as in the case of her mid-sixties documentary on Andre Masson), ignored (pulled out of circulation by those who have owned the rights), and now nearly forgotten. These days, Kaplan -- a true anomaly, whose work evades most categorization -- is likely to be discovered only by those rare seers who have what Lenuta Giuki calls a "taste for provocation." Bennadette Lafront, quoted by Chris Holmlund, points out, "[Kaplan's] personal chemistry is not of this world. her roots are with prophets, witches...."

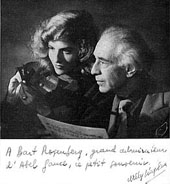

It was around 1953 when a teenaged Nelly Kaplan left (ran away from?) her hometown of Buenos Aires to move to France. She dropped out of school (where she may have been studying economics) and was apparently drawn to Paris due to the notion that the city had been built atop a temple for Isis! Having missed out on much European film (due to a lack of screenings of such material in Argentina during WWII), she was nonetheless very familiar with the work of Abel Gance. After being introduced to Gance himself (possibly at Cannes, possibly by Henry Langlois) in 1953, she was given her first real opportunity to work in the realm of film production, as his assistant. Gance's films at this point were not doing so well, his work perhaps now overshadowed by that of a younger generation of makers (25 years earlier he had been among France's top directors). Kaplan had good timing (according to Kevin Brownlow): she happened to arrive at Gance's side "just at the right time, giving him the spur of encouragement he so desperately needed." The two of them worked alongside one another for ten years.

It was around 1953 when a teenaged Nelly Kaplan left (ran away from?) her hometown of Buenos Aires to move to France. She dropped out of school (where she may have been studying economics) and was apparently drawn to Paris due to the notion that the city had been built atop a temple for Isis! Having missed out on much European film (due to a lack of screenings of such material in Argentina during WWII), she was nonetheless very familiar with the work of Abel Gance. After being introduced to Gance himself (possibly at Cannes, possibly by Henry Langlois) in 1953, she was given her first real opportunity to work in the realm of film production, as his assistant. Gance's films at this point were not doing so well, his work perhaps now overshadowed by that of a younger generation of makers (25 years earlier he had been among France's top directors). Kaplan had good timing (according to Kevin Brownlow): she happened to arrive at Gance's side "just at the right time, giving him the spur of encouragement he so desperately needed." The two of them worked alongside one another for ten years.

Kaplan's later intersection with the Surrealist movement in France is another major point of entry for understanding her influence (or, as it turns out, her obscurity). At first glance it may seem curious that Kaplan had anything to do with Paris Surrealists, after having been so close to Gance; one of the Surrealists' periodicals had famously advised the world to ignore Gance's films, recommending instead the work of: "Melies … Sennett … Christensen … Clouzot … Dickinson … Richter … Sternberg" and others. And interestingly, Luis Bunuel, when offered a job assisting Gance in 1928, basically told Gance to shove it!

Curiously, it's been suggested that Nelly Kaplan's marginality is due no less to her association with the established Gance than to her being linked to the far-out Surrealists. Gance's old-school approach to quality filmmaking was apparently just as unmarketable to the masses of a coca-cola-nized France as those subversive and esoteric "anti-classics" being offered up by Breton and Co. These two different apparent strikes against her, not to mention her general unwillingness to pander to the dictates of the industry's "art house" market with the films she's directed, give some indication of why her work has so rarely been screened or written about.

"To film our maddest dreams would be equivalent -- would it not -- to throwing the dice which will abolish chance, surrendering it to the the triumph of all revolts, of love without constraints..." Thus spoke Kaplan in one of her published pieces, entitled "Enough or Still More." It was supposedly by chance that she met one of the publishers of her work, Andre Breton (though it's worth noting she had somehow already previously crossed paths with his long-time associate Phillip Soupault). Kaplan would go on to enlist Mr. Breton to co-narrate her 1961 documentary about Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, part of a series of films about artists. Pablo Picasso would be the last artist to be portrayed in this series. He remained her loyal fan, and after seeing her later film A Very Curious Girl, the famed painter proclaimed it to be "insolence raised to the status of a fine art."

"To film our maddest dreams would be equivalent -- would it not -- to throwing the dice which will abolish chance, surrendering it to the the triumph of all revolts, of love without constraints..." Thus spoke Kaplan in one of her published pieces, entitled "Enough or Still More." It was supposedly by chance that she met one of the publishers of her work, Andre Breton (though it's worth noting she had somehow already previously crossed paths with his long-time associate Phillip Soupault). Kaplan would go on to enlist Mr. Breton to co-narrate her 1961 documentary about Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau, part of a series of films about artists. Pablo Picasso would be the last artist to be portrayed in this series. He remained her loyal fan, and after seeing her later film A Very Curious Girl, the famed painter proclaimed it to be "insolence raised to the status of a fine art."

It is both Kaplan's approach to film (which, as Michael Richardson notes, heavily valued collaboration) and the thematic content of her work, that appear to uphold Surrealist ideals quite loyally. But technically hers has remained without a capital "S" -- unlike famed animator Jan Svankmeyer, she has never formally joined the Surrealists. Her intersection with the movement has been entirely on her terms. One can't help but wonder, if she had joined, would she perhaps eventually have been expelled in the same fashion as Dali, Artaud, Desnos, et al?

By the way, who's to say how exactly one should divide off the Surrealists proper from those loosely tied to the movement or more distantly influenced by it? The word itself originally comes from Apollinaire, though it was Breton and friends who made it an institution. Chicagoans Franklin and Penelope Rosemont received Breton's blessing when they started an official American offshoot in the Sixties, but it is worth noting that by this point many observers and radicals the world over already considered the movement to be a thing of the past -- something that had perhaps been eclipsed by Existentialism, the Situationists, LSD mysticism, Deconstruction, or what have you.

Like the painter Joan Miro, Nelly Kaplan has remained Surrealism's intentional neighbor throughout -- persistently and subversively cultivating her individuality, regardless of the degree to which she has been found to be under the influence of any manifesto. Kaplan once summed it up as follows: "Painting and color, beauty and convulsion, cinema and surrealism - certain relationships are so so self-evident that we end up ... no longer perceiving them."

One historian, Stella Behar, has included Nelly Kaplan in her category of "neo-surrealists," which for her also includes Andre Pieyre de Mandiargue, Julien Gracq, Gerard Klein, Jacques Sternberg, and Roland Topor. Alejandro Jodoroswky (of whom Richardson takes note) is another which might be added to this list, and it is worth pointing out that Jodorowsky shares with Kaplan an interest in the Tarot; Jodoroswky's early 70s countercultural classic, The Holy Mountain, borrows much from the imagery and philosophy of the Marseille Tarot (Breton's favorite deck, by the way), while Nelly Kaplan makes overt references to cards such as the Hanged Man in her film Plaisir d' Amour.

Kaplan’s modus operandi (to again quote Michael Richardson) seems to entail a "vengeance against everything that is sordid in life." Kaplan herself (still alive by the way), has said that one "cannot -- indeed should not -- accept life as it is" and on at least one occasion has called for "eroticists" of the world to unite. From alchemy and insurrection to wilderness, magic, androgyny, and mad love -- these are Nelly Kaplan's obsessions and motifs; let future audiences, should they have the good fortune to stumble upon her, decide whether she's a Surrealist and whether it matters.

◊