Experimental Now!

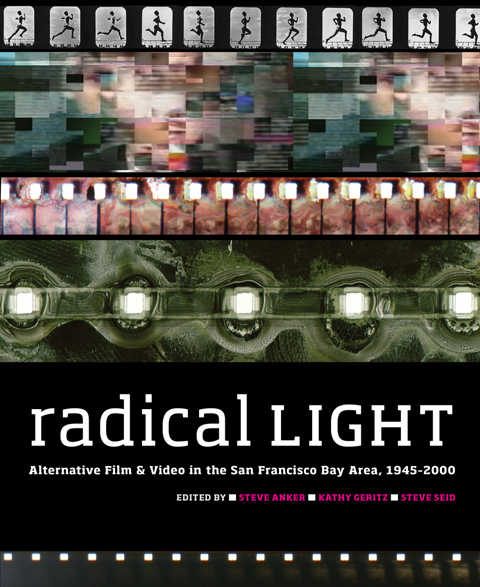

radical LIGHT--The Book

15 Feb 2011

'Garden of Earthly Delights', Stan Brakhage

Fantastic homegrown venues

Radical LIGHT: Alternative Film and Video in the Bay Area, 1945-2000, is the book document of the cultural development of remarkable moments in a remarkable film scene, the history of its political transitions, and its most important works, with much emphasis upon Canyon Cinema's early development as the off beat beginning of the extraordinary SF Cinematheque, then later as a collection and avant-garde distributor. radicalLIGHT is carefully conceived to express the many significant overlaps between curators, filmmakers and visual artists, film departments, film and art schools, and arts institutions which transformed the growth of Bay Area filmmaking to form and sustain 55 years of film exhibition, education, practice, and pleasure. radicalLIGHT also, marks a moment, the end of a particular era of filmmaking, and its beginnings, and breadth of national and international influence.

Super 8...

Of particular interest and worth, for this author, is the in depth knowledge of films made in super 8 technologies contained within this highly personal volume of essays. Super 8 died as a medium in the nineties, yet helped make film art possbile. Both film technologies, 16mm and super8, with their relative low-cost and portable formats,were the backbone of experimental film culture from 1940s to the 1970s, well into the eighties and early nineties. They are and have been rightly mourned for passing from our hands largely into the realm of archiving, and out of our audible and visible realm of enjoyment, along with the crackling sound of the 16ml projector. Once novel, accessible, state of the art tools: these technologies were easy to obtain, carry and remarkably inexpensive consumer items, and/or plentiful in professional and non-professional environments. Thus,they were used by amateurs and visual artists alike to make feature films or create the components of a live multiscreen projection event, where the precarity of the splice, the thrill of mixed projection, or the combination of performance and home-made films made the work special, fresh, and original.

Much space in radicalLIGHTis made for sweetly-remembered recollections and reiterations of the truest heartbeats in the scene--weekly backyard, basement, garage, or warehouse micro cinemas! (a term attributed, for its coining, to Rebecca Barten and David Sherman of Total Mobile Home.) Canyon Cinema, Other Cinema, No Nothing Cinema, and Total Mobile Home were the foundations of regularly-programmed, experimental film exhibitions, places where film enthusiasts were exposed regularly to dozens of amazing works, the milieu of makers, and the poetry of the cinematic community. Considerable ephemera and verbal evidence of these venues, plus mention of other less reknowned "movements", illustrate and color the text.

'10/65 Selbstverstümmelung' by Kurt Kren, part of Austrian Avant-garde cinema tour at Total Mobile Home

Enter Video

Some might suggest that video technology was to blame for the end of film as art, in the sense of the 'authority of the image' and positioning of originality. Video certainly contributed to the growth of easily reproducible experience, thus,changing how makers thought about what they were doing and the value of "screening". Video enabled both popular culture and mainstream media/television images to be utilized more readily, for instance, in experimental works and helped spark debates around copyright, control of media by corporate power and the invisibility of underrepresented communities in both art and news. Whereas, film as art, was to some extent a selfconscious attempt to create images outside of media culture, its makers now had to contend with the influx of borrowed and found images across the moving imagemaking spectrum.

Video Art and News

Video surpassed celluloid in terms of accessibility and affordability by quickly replacing 16mm in professional documentary news and field work from the 1960s onward. Most importantly, video did away with the expense and lag time of chemical processing, while meshing easily with television. For lay persons' and home movie making, video's affordability and convenience was surely superior to that of super 8 and from early on video was adopted by artists as a "documentary" tool in performance and conceptual art. The late Nam Jun Paik purchased a SONY Video Portapak in the mid sixties and broadcast himself from his Soho Manhattan loft. Lynn Hershman owned was given a video camera in 1966, "figured out how to use it", and taped whomever walked into her living room. [1] Wolf Vostell, the SI and Ant Farm fooled with domestic television formats in their work, and by the late sixties, video art installations began to appear, challenging conceptions of artmaking, an aspect of video work which has continued well into the 1970s, 1980s, and beyond.

Video v. Film

Of course, as an image, the aesthetic quality of video was substantially different from that of film, and artists had to deal with it. It also had its own formats: Hi8, 8mm, SVHS. And as soon as artists could make and manage images more simply, much changed. Then, nonlinear editing started also shaping consciousness of film production. Toasters, Avids, and Media 100's presented makers with the specter of non-linearity as celluloid was transferred to video, digitized(compressing the VHS or SVHS), put through these systems, organized shot by shot, and edited and reedited endlessly without damage to sprockets! Goodbye flatbeds, splicers, and Steinbecks! Hello, After Effects, and USBs. Powerful laptops--the G3--reduced production hiccups from shifting platforms,(SCSI to firewire to USB connections, for instance), even more, with their early versions of Final Cut Pro, increasingly moveable and spacious storage, plus miniDV and digital video cameras!!!Whole new conditions arose which now changed how filmmakers worked with and thought about the image.

The book documents the artists' groups, artistic movements, film and video exhibition and distribution practices, film schools, publications, and media art centers that were central to the blossoming of avant-garde film and video in the Bay Area--Lawrence Rinder, BAM/PFA, Director

Segue

Now, of course, digital filmmaking has all but taken over. Entire schools are devoted to its teaching. While this educational and industry shift is discussed only in bits and pieces throughout radical: LIGHT it is an especially important one because new generations of filmmakers have learned to make film without touching a piece of film stock. Special light is thus cast upon departments such as San Francisco State's where hand processing is still taught, or where the work of scratch artists is still encouraged. The image is the enjoyment, no matter how it is made. Yet, in this recognizable transition towards digital filmmaking and new media imagemaking, Jim Campbell, Rebecca Bollinger, Lynn Hershman, Alan Rath, and other artists did much to create sophisticated meaning with which to communicate digital fine art and cinematic ideas. Special "focus" sections are devoted to their work.

The life of the scene moves it through time.

Enter Digital Media!

Almost as soon as personal computers became available, artists started doing something called "multimedia". Perhaps, not surprisingly, the mix of moving image and machine brought about attempts to mingle old skills such as the look of hand coloring and texturing with popular culture and this strange, new fangled, decentralized independence from older forms began not only to shape editing issues, but also to develop into a new set of aesthetic concerns. Making digital less than boring and sterile was at first difficult. Hypertext comic books by artists such as Mike Mosher bridged old, familiar forms and then new surfaces of multimedia. In other circles, personal narrative filmmaking gave rise to "digital storytelling" and then filmmakers discovered that HD looked almost better than film and nothing changed. Hybrids of video, web-based art, digital projection, and online practices merged with filmmaking and aesthetic techniques. After Effects became a tool of cut n paste, or cut out experimental animators.

Digital Archiving

But, beyond the dwindling requirement of tape or yards of celluloid and gobs of cash to make a feature, and beyond the relative low cost, was

another critical departure to which digital media has contributed:

the shift in archiving and storage of precious images and footage. Both DVDs and the Web, play a hand. The Internet Archive stores terrabytes of films for online access. For the indie maker or average consumer, it is simpler and easier to collect and store films if they are on DVD and with laptops, they are easily playable. The DVD thus fosters independent distribution and sharing of films while the necessity of owning the original lies with a film archive. Neat jackets can be designed, and liner notes, and tons of extra bits can be added to DVDs, making them highly desirable and collectable.

This is where film archiving has gone digitally. Brakhage's fly's wing now rests, in digital glue in a digital version, with the carbon residue lying elsewhere, one version, once made, while incredible film archives of originals, in cans, in cold storage, monumentalize a past of hand proceesing and hand coloring,labs, darkrooms and the trading and lugging of film cans.

A wonderful, multi-dimensional companion exhibition ran through Fall 2010 with curated programs in various Bay Area film venues: Artists' Television Access, Victoria Theatre, Pacific Film Archives, Berkeley Art Museum and SF Cinematheque,to accompany the publication of the book.

◊

Related links:

radicalLIGHT project

http://press.bampfa.berkeley.edu/radical/Underground Film Guide

http://www.ufilmguide.com/More on No Nothing Cinema

http://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=NO_NOTHING_CINEMA

References

[1]

Post to faces-list serve, Feb 19, 2011