Mermaids, Nazis, and Famous Monsters:

Cary Loren's '70s Super-8mm Michigan

10 Feb 2013

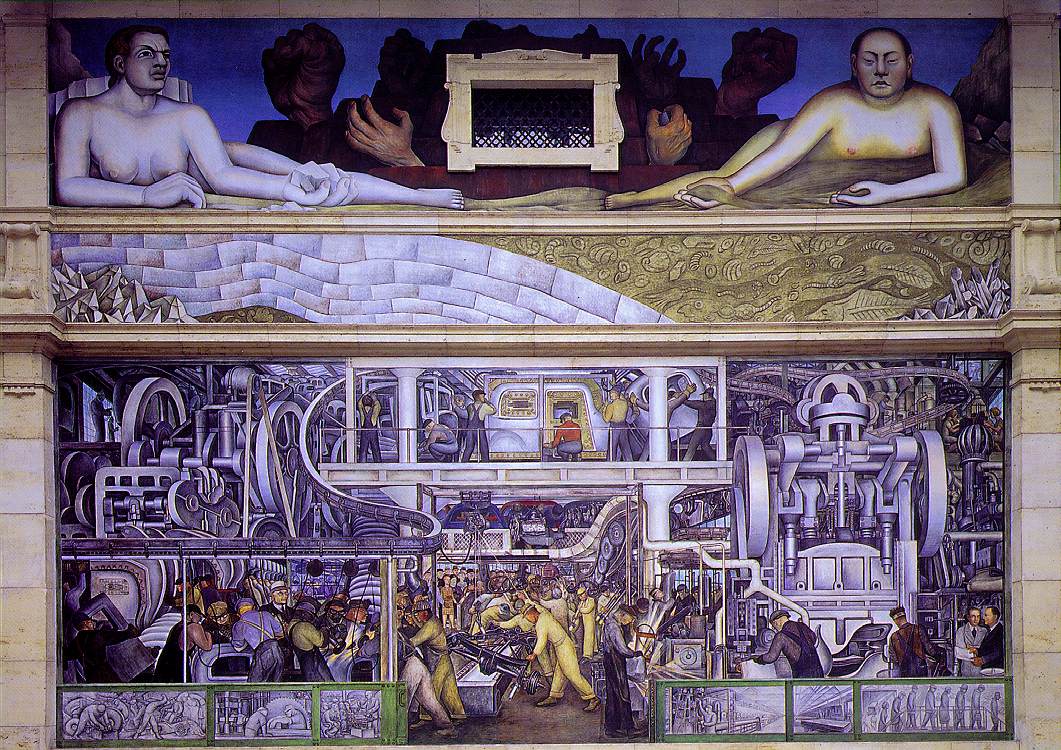

Diego Rivera’s 1933 Detroit Industry fresco cycle celebrates the multiracial assembly lines, various immigrants from northern and southern European stock, Mexicans, whites, and blacks recently transplanted from the American South. To this day, to understand Detroit, one needs to examine its ethnic strands, conflicts and interfaces. Southeastern Michigan’s Cary Loren, Berkley High School Class of 1973, was a young filmmaker in a Detroit suburb. He met his New York filmmaking idol Jack Smith, then moved to Ann Arbor. With various arty, dramatic friends, his Destroy All Monsters collaborators, he produced a series of films (collected in the anthology GROW LIVE MONSTERS) that juxtapose and superimpose skits, photos, and monster movies off the TV, atop jarring noise music. Loren brought an edgy big-city aesthetic to the mellow university town, with disturbing blood-and-guts imagery, and some artistic nudity. Smith’s flamboyant influence is evident on Loren’s mermaid movies, on the Jewish teenager’s odd take on the Holocaust. Almost four decades later, Loren’s latest cinema harmonizes with the aesthetic of African-American artists in Detroit.

I. Watch-Me Teen Goes to Mr. Smith

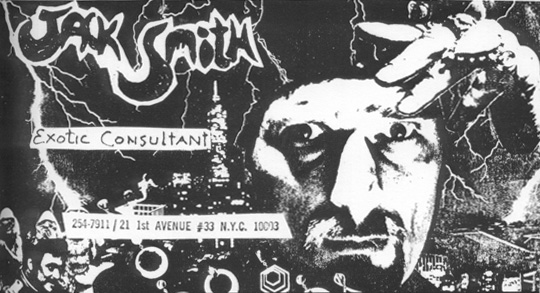

Loren has been open and loquacious about his work and influences, and in 2002 was guest editor for issue #13 of the online ‘zine, Blastitude. In an issue that also remembers Wallace Berman, Angus MacLise, and other creatives of the generation before his own, Loren provides fond reminiscence of the late Jack Smith. He discusses his films, and Smith’s mark upon them, in an interview with “Fuzz-O” Dolman.

In the 1960s there were numerous movie shows on Detroit television, hosted by Bill Kennedy, Rita Bell, and others. Monster movies especially inspired him.

Loren’s father loaned him a simple 8mm camera when the lad was about 12, but he got a Super 8mm at age 15, which he used well into the ‘70s. He showed his movies to teenage friends at marijuana-fueled parties, at a “Happening” held at his high school, and when living in Ann Arbor, at the University of Michigan’s 8mm festivals (co-organized by OtherZine contributor Gerry Fialka).

In the early ‘70s Loren gobbled up films like others might Goobers. He appreciated the intensity of silent films, Mélies and Von Stroheim, Dreyer, Lang and Murnau, Cocteau and Feuillade, later “underground” filmmakers Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, Robert Frank, Ron Rice, and animator Harry Smith. He was convinced that:

Loren appreciated both the lush vision of Federico Fellini ’s JULIET OF THE SPIRITS and the cheap, improvisational John Waters. He admired Andy Warhol too, for “deadpan, flat, and boring technique,” bad lighting, poor dubbing, miscues, rough edges “that had mesmerizing results.”

Yet Jack Smith—whose FLAMING CREATURES was shut down when it played in Ann Arbor in 1967—was Loren’s major inspiration, “the center of his film cosmos.” He read copies of Film Culture in the Detroit Public Library, and especially appreciated Smith ’s contributions to it.

Loren fondly recalls hitchhiking to New York, turning up at Smith’s apartment and the details of fussy, exotic sequined and bejeweled decoration therein, under colored lights, fabrics, masks, and stagey bric-a-brac. When cockroaches in the apartment got too disturbing, Smith and Loren would hunt the streets for discarded furniture and potential movie props. Smith set up a showing of Loren’s ELMO THE GEEK and SILVER-TINGED COFFINS OF VENUS to a respectful audience at Millennium Film Society. Loren carried his films there in a paper bag, which urban Smith advised was the best way to confuse potential muggers, as no one knows what you’re carrying in the bag. When technical problems loomed, Smith amiably told stories and filled the space while Loren recovered.

His ideas came along and knocked you out—his imagination was overflowing. He was one of the funniest and most dead-on perceptive people I’ve ever met.

Smith “added magic to everyday life.”

Feeling that further film study would be futile, weak, and ineffectual after his experience with Jack Smith, Loren nevertheless moved about 25 miles west, to the university-dominated town of Ann Arbor. There he gathered participants in nocturnal film and performance projects, often filmed and/or with films projected upon the stage and actors.

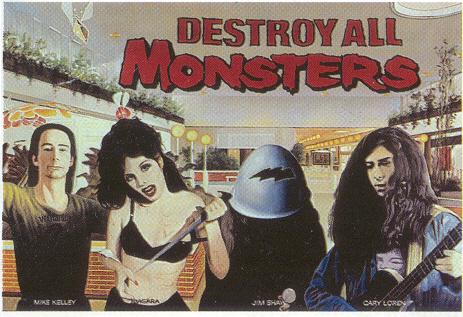

In the summer of 1974 Cary, his girlfriend Niagara, and University of Michigan College of Art and Design students Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw coalesced into Destroy All Monsters. They re-invigorated Ann Arbor’s own local teenage psychedelic scene, and got its psychedelic musicians and comics artists into elaborate costumes and cosmetics. This was less difficult than one might expect, for this was the height of the glam-rock era. As in Smith’s performances and films, scenery and scenario often self-destructed, signaling conclusion.

Loren’s filmmaking method involved “painting on frames, scratching on emulsion, using bleach, vegetable color dyes, magic markers, chemical toners, anything.” Unable to afford professional film-splicers, scotch tape and razor blades had to serve their function.

The layering of film is related to this processing, and [to] chance, you never know exactly what the effect will be. In one sense film is just background, like psychedelic light shows; they get into your mind and behave like a drug. They alter your mood, or they become like a fireplace, something to gaze into.

Loren and Smith also shared the motif of lobsters, something that helped endear the young Detroiter to the older Gotham denizen. A trip by Loren and Niagara and a couple other friends to Miami Beach generated the movie cycle TALES OF ATLANTIS: HORROR OF BEATNIK BEACH, THE MERMAID’S EGG, and KING NEPTUNE’S GARDEN. To watch these today, strung together on Loren’s GROW LIVE MONSTERS anthology, they view like a single movie with multiple scenes.

Jim Shaw constructed a fish-head mask for them, but didn’t join them on the trip. A mermaid (Niagara) emerges from the sea, and while lounging on the beach, is menaced by a Hitler-moustached lobster-clawed monster, played by Loren and Niagara’s school friend Robert (Bobby) Epstein. Another school friend, David Keeps, played a mad scientist in a checkerboard lab coat who attempted to steal the mermaid’s egg. People on the beach stroll by, look, but walk on.

In 2002 Loren recalled:

II. Death Camp for Cutie

THE NINTH DAY (1974–75) today looks like Loren’s most “political” or “serious” Super-8mm movie in the ‘70s; it ’s certainly his weirdest, most decadent, and problematic. Zechariah 7:5 notes the “9th Day of Av” or “Tisha Be-Av,”—“when you fasted and mourned in the fifth month and in the seventh”—is traditionally a day of fasting or mourning and remembrance of Israel’s sacred Temple burned to the ground. The 9th of Av is the date of the destruction of Solomon’s Temple by the Babylonians (587 BC), the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans (AD 70), and the day that the Roman army plowed Jerusalem with salt (AD 71). It was also the day Simeon Bar Kochba’s army was decimated (AD 135), England (1290) and Spain (1492) expelled all Jews, and World War I was declared (1914). Loren further associated the date with the Spanish Inquisition, Hitler signing orders for the Final Solution, and eventual arrival of the Messiah.

Loren had juxtaposed Niagara’s frightened beauty, a knife and (stage) blood earlier in YOU CAN’T KILL KILL, essentially a menacing music video accompanied by their own throbbing rock song. But that was just a cinema noir snippet, elegant violence of a type Niagara made effective use in her 1990s gangster moll paintings, when compared to the surreal anti-Semitic murder at the center of NINTH DAY.

The movie opens with Niagara painting a sign with the movie’s title in red paint. She picks up a heart-shaped candy box full of live mice. A young man holds a pineapple, his white face and long hair making him look like Roxy Music’s Brian Eno. Niagara’s violin bow is sharpened upon a spinning wheel. Pale-skinned, in a black dress, her long hair cascading, Niagara plays the melancholy violin (and her sawing notes appear on the film’s soundtrack, juxtaposed over ant-monster chirps from the 1950s sci-fi movie THEM). Then a knife is sharpened on that wheel by the scabby (heavily made-up) hand of a moustachioed guy with TV-screen glasses, who smiles wanly. Intercuts from PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE. Cut to the beardless whiteface. Vampira! Hitler, played by Bobby Epstein! More Niagara on violin!

A supine victim (played by Link Yaco)—“JEW” sign upon his skinny chest—is wounded, gory, but all red and white like an enticing birthday cake. Bits of him are sawn off with the knife, for the assembly to eat. Niagara takes a bit, licks lips, wipes her face; Hitler gorges himself, his eyes wide, while TV Eyes smiles, nibbling a bit of the victim decorously. Vampira advances. Are noodles standing in for viscera? Cut to a grotesque green corpse-head, perhaps a sculpture by Jim Shaw.

Hitler’s head floats over PLAN 9’s Tor rising from his tomb, electronic video-studio effects enabling their co-existence onscreen. Niagara licks lips, fingers, clutches the candy box to her midsection. Loren, a swastika on his t-shirt and corpse makeup on face, drinks blood, spits it up all over himself, stabs the pineapple, beats himself on head with it, strangles himself. Video effects flash. A domestic room, Niagara enters kitchen, then is in the same basement as in CAN’T KILL KILL. Close-up of her smoking a cigarette, as if after sex, caressing her nipple.

Allusive but inconclusive, Loren called THE NINTH DAY his “explosion of negativity.” He explained that it’s a pantomime about Auschwitz’s “slave-labor musicians that would play as you came off the trains and entered the crematoriums,” not a “statement.”

Loren says he’d been reading magick and Kabbalah, and conceived of his appearance vomiting blood, strangling himself, and hitting himself on the head with a bomb-like pineapple (that he previously attacked with a knife) as a representation of “total annihilation.” The tiny white mice in the valentine heart are supposed to be a “symbol of light,” which vampiric Niagara threatens to eat.

For years the film seemed odd and creepy to this viewer, inexplicable in its Grand Guignol flippancy, for Jewish friends have said elders with concentration-camp tattoos and horrible memories in their community always reminded them that Nazism was no laughing matter; America’s first Holocaust memorial center was dedicated in a nearby Detroit suburb, West Bloomfield, in 1984. One struggles to put Loren’s THE NINTH DAY into context. Perhaps Abraham’s thwarted sacrifice of Isaac weighs in here somehow, or the Christian communion, where one Jew’s body and blood are ingested, is parodied. As Link Yaco was a local comics/SF writer, artist, editor and collector, Cary might have been trying (unsuccessfully, evidently) to kill his own young Man of the Book within. Susan Sontag—s essay “Fascinating Fascism,” in the New York Review of Books in 1975, acknowledged the near-pornographic appeal of Third Reich Regalia, and London Punks Cary’s age began wearing swastikas to upset the WWII generation. Or perhaps it’s really all only on THE NINTH DAY’s fabulous surface.

Around 2010, Los Angeles artist Joyce Lieberman began to post photographs on her Facebook pages of cheerful 1960s Jewish community events around Berkley and Huntington Woods, MI that included Purim holiday carnivals, with children costumed in foil crowns, headdresses, beads, and finery to represent ancient kings and queens. Cary Loren is one small, bespectacled boy in those photographs. So we begin our NINTH DAY recipe with that festive love of holiday dress-up. Mix in the formal conceits of monster and low-budget horror movies broadcast on Detroit television for the fascination of kids too. If you want an antidote or inoculation against an outrage like ILSA, SHE WOLF OF THE SS, viewed in the early ‘70s by Loren, then liberally spice your answer to it with the over-the-top camp performance style learned from Jack Smith. The end result is NINTH DAY’s fey and uniquely disturbing Hebrew School alumni Post-Hippie Nightmare. I wonder how the actors’ parents savored this Manson family early-bird buffet, its flesh and pineapple dishes.

III. River Rouge Reconciliation

Cary attended Eastern Michigan University off and on for about two years between 1974–78—which gave him access to film and video equipment, and graduated from Wayne State University in 1979. In 1982 he and his wife Colleen Kammer founded the Book Beat, a bookstore just outside of Detroit in the suburb Oak Park, not far from where they grew up; the store is distinguished for its inventory in Art and Photography, Judaica, Children’s Literature, and African-American Studies. In 1996, Loren produced two videos and CLEAR DAY and SHAKE A LIZARD TAIL, OR RUST-BELT RUMP. In the latter, African-American dancers in the 1960s are further aestheticized with sheets of color and special effects.

The episodic STRANGE FRÜT PART 1: ROCK APOCRYPHA (1998) re-contextualizes the Detroit culture and its promulgators that Loren grew up amongst. Late-‘60s WABX radio personality Bob Rudnick reflects on the era, and Loren interviews ribald Soul songwriter Andre Williams, who wrote and recorded songs “Bacon Fat” and “Jail Bait.” In the video’s most novel and amusing segments, White Panther Party texts from 1968 to 1972, as well as a few Detroit children’s television routines, are read in deadpan sotto voce by late-1990s teenagers. It is arresting to watch youth in Goth trappings, in contrast to expected hippy freak garb, voicing these phrases, so rooted in their own time.STRANGE FRÜT was a commissioned project for the I Rip you, You Rip Me exhibition that celebrated Detroit culture—jazz poet-qua-White Panther Party Minister of Information John Sinclair was a participant—at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Destroy All Monsters’ contribution included banners commissioned for the show that Mike Kelley and Jim Shaw designed and had painted by Dutch professional sign painters. Two more banners were painted for the Detroit 300 show at the Detroit Institute of Art in 2003, one including images of Loren, Niagara, Kelley and Shaw around 1975, situated in the suburban Westland shopping mall. Though VHS copies of STRANGE FRÜT were available at the Book Beat a decade ago, following the sale of the banners and film to a Toronto collector, it appears the video is no longer generally available.

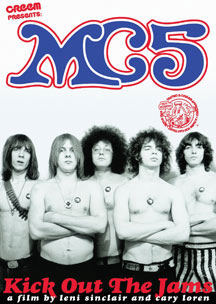

Following that, Loren produced the impressionistic MC5 KICK OUT THE JAMS with Leni Sinclair in 1999, setting his silent footage of the band to live recordings of comparable performances. He then produced limited-edition DVDs entitled THE CANDY GOLEM (2001), FANTOMASH (2002), FEAR FINDER (2002–03) and—in the musico-political tradition of the MC5—BANDS AGAINST BUSH: MONSTER ISLAND AND THTX (2003). In February and March 2010, Loren showed versions of a work-in-progress called BANZAI DETROIT in Berlin, Germany and Tilburg, the Netherlands.

As Michigan affirms its postindustrial (post-Fordist) reality, Loren resembles the Dakarois artists who made use of recycled materials after Structural Readjustment crippled the economy of artists in Senegal in the 1980s. He makes use of outtakes, old Super-8mm footage, ephemera, photos (there’s Francesca Palazzola! There’s Ben Miller! Their Japanese fans!), and various memorabilia of the Monsters post-1995 resurgence in the MONSTERS REDUX videos on the GROW LIVE MONSTERS DVD. Autobiography blossoms as montage and dynamic collage. A 2000 Destroy All Monsters exhibition and performance at Seattle CoCA was co-curated by Paul Remley, Professor and Middle English scholar at the University of Washington. Once an actor in Loren productions (then-longhaired Remley examines a woman’s leg with odd protruding-eyeball spectacles in Loren’s OVERSTIMULATED MOUTH OF HELL), Prof. Remley moderated a panel of Kelley, Shaw, and Loren on “Rust Belt Noise, Thrift Store Aesthetics, and the Globalization of Detroit Pop Culture.”

When teaching art students today about Destroy All Monsters, I emphasize that that while they were exemplary, they were not alone, for Ann Arbor in the ‘70s was a time of ubiquitous moviemaking, in Super 8mm and Sony video Portapak. Teenagers were constantly “making a movie,” even using that as an excuse when found doing something questionable where they weren’t supposed to be. Loren’s work can be compared with Ann Arbor’s Jimm Juback. Juback played music with Loren on occasion, though never collaborated on a film. There is a family-friendly silliness in Juback’s movies like DANIEL BOONE or THE GUY FROM ANOTHER PLANET (disclosure: this author was involved in both productions) or WHAT GOES UP (MUST COME DOWN), in contrast to the eroticism and violence in Cary Loren’s. Juback apes the forms of the small screen’s situation comedy, skits and vaudevillian shtick, yet while Loren peppers his print collages with TV and movie stars, his films mostly mix Kenneth Anger-style editing with Jack Smith mise-en-scène and stagecraft. Nevertheless, the sloppy, floppy ’70s Super-8mm spirit evinced by Juback and by Loren seemed present at the 2010 College Art Association conference in Chicago, IL, when Elliott Earls, Professor of Design at Cranbrook Institute in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, showed his 2007 movie, SARANAY MOTEL. This broad comedy, perhaps inspired by Eminem ’s “8 Mile”, is the story of the rise and fall of a grotesque white hillbilly rapper. One wonders to what degree Prof. Earls was aware of his southeastern Michigan predecessors.

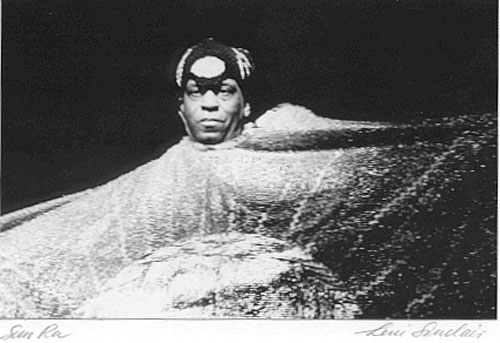

Both filmmakers Loren and Juback displayed a certain dandyism in their ‘70s work, and could be accused of avoiding contemporary political, social and especially racial issues that were so rending Detroit, and to a lesser degree, Ann Arbor. Yet Loren’s attentiveness to his black neighbors has grown over the years, as he manages the Book Beat bookstore at the city’s edge. In the Loren-edited Blastitude, Ben Schodt writes appreciatively of the “Astro-Black Mythology” of avant-jazzman Sun Ra, and Leni Sinclair’s photographs document Sun Ra’s splendor.

©Leni Sinclair

In 2012, Loren affirmed the biracial culture of Detroit when he collaborated with septuagenarian black artists Aaron Ibn Pori Potts, M. Saffell Gardner, and members of the Ogun Kcalb Gniw Spirit Collective on the Vision in a Cornfield installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Detroit (MOCAD). The idea originated with a weird car seen in the late 1990s by Loren and Mike Kelley when they went to investigate the site of a 1960s UFO sighting in rural Michigan. Besides wall decorations, including ‘70s collages from Destroy All Monsters Magazine that are agreeably similar to those of Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts, both Pitts and Loren display collected ephemera and bric-a-brac in big side-by-side vitrines. And on a screen cut into one wall, Loren contributed a video, which cycled in the gallery. Lore ’s characteristic DAM-style montage and video collage cuts between Mexican horror movies and Caribbean carnival dancers, Blacula and Rudy Ray Moore, a tree-monster and Isaac Hayes, BASQUIAT and Lando in Star Wars, and One String Sam at the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival, 1973. In a sequence as dense as his ‘70s multilayered mashups (though, alas, minus the antics of a youthful cast) Loren cheerfully mixes Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and Marlene Dietrich in tropical drag in “Blonde Venus”, Jamaican record producer Lee “Scratch” Perry, anthropological films from the West Indies and Africa, Jimi Hendrix, and other visually, sensually rich notations.

In Loren’s part of Vision in a Cornfield, the suburbs of Detroit (many built by Jewish developers whose children Loren knew) makes peace and harmony—or jazz harmolodics—with the city’s black aesthetic rooted in the other side of Woodward Avenue. As in every American city, ethnicity can spell destiny. And creativity. Link Yaco, who co-produced and filmed Juback’s THE BOY-GIRL WAR and played the sacrificial victim in Loren’s THE NINTH DAY, once parsed his Ann Arbor friends of the ‘70s into three (surprisingly) old-fashioned ethnic categories. There were terse, tight-lipped Germans, which included Destroy All Monsters musicians Ben and Larry Miller, and Loren actress Ingrid Good. There were jovial, laughing Catholics like the Slovak Juback, BOY-GIRL WAR actor Mark McNally, and—thanks, Link—this reviewer. And then, oy, there were Yaco’s fellow “neurotic” Jews, like his NINTH DAY cast mates. Cary Loren may have had conflicted moments in his youth when he was at war with himself, yet the creative artist Loren was definitely at his least neurotic when he was making his movies with his pals. When a camera was rolling (or in the editing process) he commanded his merry troupe with intuitive confidence, and flourished at his most dedicated, expansive, and expressive.

◊

Mike Mosher is Professor, Art/Communication & Digital Media at Saginaw Valley State University in Michigan. He has contributed to OtherZine, Bad Subjects, Leonardo Reviews, Smokebox, often on Michigan culture. He was a community muralist in San Francisco in the 1980s and did onscreen graphics in Silicon Valley in the 1990s. Mike’s own videos and films in Super-8mm and 16mm were shown at Artists’ Televsion Access gallery in 1996.