THINKING BIG ON SMALL-GAUGE

FILM: MIKE KUCHAR STILL VOICE OF INDEPENDENCE

by Jack Stevenson

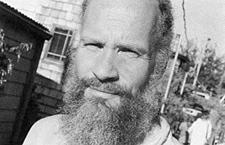

When Mike and George Kuchar first got their hands on an 8mm movie camera

in 1954 as 12 year old boys, no one really thought the format was suitable

for anything but  vacation

footage, yet since then no one in America has contributed more to the

craft and philosophy of personal film-making then the twin brothers from

the Bronx. In a culture of hype and careerism, where "size counts", its

not surprising, then, that gangly, self-effacing Mike Kuchar, the lesser

well known of the two, is not in any sense famous.

vacation

footage, yet since then no one in America has contributed more to the

craft and philosophy of personal film-making then the twin brothers from

the Bronx. In a culture of hype and careerism, where "size counts", its

not surprising, then, that gangly, self-effacing Mike Kuchar, the lesser

well known of the two, is not in any sense famous.

From THE WET DESTRUCTION OF THE ATLANTIC EMPIRE in 1954, the first of his co-produced 8mm home-movie melodramas, to his emergence as a key figure in the New York underground film scene of the sixties eleven years later, with SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS, to a string of subsequent personal and student productions and his current work today in video, Mike has always been a practitioner and advocate of film as a creative and affordable means of personal expression rather than as a product to be packaged for the masses.

To Mike Kuchar, each film exists as a separate entity unto itself, a culmination of the specific collaborative energies, talents, looks and ideas involved, the result of fugitive mixtures and situations which could never be duplicated or re-staged. He never saw film as a calling card or a stepping stone to a career. In the competitive class-structured world of film-making, full of elitism, snobbery, egotism and raw careerist ambition, Kuchar remains a disarmingly unpretentious, straight-forward and firmly grounded if occasionally volatile figure, playing neither the role of aggrieved rebel nor divinely principled purist - refusing even to join the hue and cry from the independent film community about the lack of funding and support for film-makers in America.

Mike and George ended their collaborative approach to movie making in 1965 when Mike phased himself out of their first 16mm work-in-progress, CORRUPTION OF THE DAMNED, to concentrate on a futuristic science-fiction fantasy which would turn out to be the 45-minute SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS, and which featured George in probably his finest acting appearance as Gianbeano, the evil prince.

A year later George completed HOLD ME WHILE I'M NAKED, an engaging,

impressionistic

rumination on life, love and loneliness in the Bronx which ran 15 minutes

and, like SINS, was shot in glorious 16mm color. These two films would

come to stand as their respective signature efforts and qualify as key

works in the canon of sixties American underground film-making.

impressionistic

rumination on life, love and loneliness in the Bronx which ran 15 minutes

and, like SINS, was shot in glorious 16mm color. These two films would

come to stand as their respective signature efforts and qualify as key

works in the canon of sixties American underground film-making.

Although their films would always display some stylistic similarity, reflective of their common love of fifties' Hollywood melodrama and their low-budget orientation, Mike dealt more with classical or Romanesque imagery that tended to have erotic under-currents, while George would go on to pioneer a form of personal film-making that relied heavily on first-person narration and his own presence in the frame - a style which he has honed in his prolific "video-diary" output of the last decade. Mike has always taken a more off-screen role in his own films, which are just as personal but in a different way, and tend on average to be longer than George's.

Mike's work would span a range of subjects and techniques and he never established a consistent trademark style like George. Even his two major works of the sixties, SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS and THE SECRET OF WENDEL SAMSON(1966), made only a year apart, are very different films. His output over the years was more sporadic and less prolific than his brother's, all of which helps to explain why George has a higher profile than Mike today. George's employment as a film teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute for almost thirty years now as also contributed to his somewhat broader recognition.

While Mike has taught at various film schools on occasion, and has worked

steadily at The Millennium Film Workshop in NYC over the years, he never

secured the type of tenured refuge at a teaching institution that has supplied many of his compatriots from the sixties

with a steady paycheck and the accessibility to equipment that would facilitate

the continuance of their own work. Although the Kuchar name is fairly

well known in independent film circles, Mike never achieved the visibility

of fellow underground notables like Bruce Conner, Larry Jordon or James

Broughton - let alone the star status of the movement's top luminaries

like Warhol, Brakhage and Anger. His film work is not yet available on

video, and SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS, which stands as a classic of

American underground cinema, and which John Waters unfailingly credits

as a major influence - remains largely unseen and tenuously distributed.

Mike Kuchar is, by any measure, unjustly overlooked.

institution that has supplied many of his compatriots from the sixties

with a steady paycheck and the accessibility to equipment that would facilitate

the continuance of their own work. Although the Kuchar name is fairly

well known in independent film circles, Mike never achieved the visibility

of fellow underground notables like Bruce Conner, Larry Jordon or James

Broughton - let alone the star status of the movement's top luminaries

like Warhol, Brakhage and Anger. His film work is not yet available on

video, and SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS, which stands as a classic of

American underground cinema, and which John Waters unfailingly credits

as a major influence - remains largely unseen and tenuously distributed.

Mike Kuchar is, by any measure, unjustly overlooked.

On the other hand, he has stayed active over the years, working on his own films and occasionally as a cinematographer on other independent productions, usually in Europe. A gifted painter and illustrator since his teens, he's derived some income from story board work and contributed to a number of gay erotic comic books. Combined Kuchar Brothers retrospectives screen periodically in America at venues such as New York's Film Forum, where in July of 1999 their early S-8 films were presented. Mike also occasionally tours his films in Europe and presents his work at festivals there, his most recent appearance being in July of 1999 at the Curtas Metragens International Short Film Festival in Vila Do Conde, Portugal.

REFLECTIONS FROM A CINEMATIC CESSPOOL, recently published by Zanja Press in Berkeley (ISBN: 0-915906-34-1), with an introduction by John Waters, has given both Mike and George a forum on the printed page, and Mike's hilarious story about a star-crossed trip to the Himalayas to shoot a film is worth the purchase price alone.

For anyone interested in the milieu and the personalities of the sixties underground scene, or the ideas and principals on which it was based in its truest form, Mike is an insightful source of information.

He is still today "possessed" but not self-absorbed, passionate and perhaps impatient but not unduly sentimental or affected - a realist by necessity but still a confirmed day-dreamer. He is a survivor of sorts, but no fossil, a man who hasn't lost his hunger to create or his keen eye for the absurd moments and screwball imbroglios that come with the territory of lowbudget film-making.

Mike, just returned from Portugal to San Francisco's Mission District, where he shares a cheap walk-up flat with George, answered my written questions in neatly executed long hand with thoughtfulness and thoroughness.

You Were a key participant in the New York underground film scene of the sixties. Do you have any particular memories about your compatriots in that scene?

The "scene" in the sixties was stimulating. Artists, beatniks and other misfits were dropping their pencils and poetry-filled note pads and picking up movie cameras to experiment and express themselves with.

I knew a lot of them. Jack Smith, he was crazy; a tormented character

forced into the predicament of existence. Even his voice had the deep wailing tone of

a dirge. It always sounded as if he was mourning and moaning, and he was

subject to violent, temperamental mood swings. A poetic nut case whom

you wouldn't want to spend the night with alone.

predicament of existence. Even his voice had the deep wailing tone of

a dirge. It always sounded as if he was mourning and moaning, and he was

subject to violent, temperamental mood swings. A poetic nut case whom

you wouldn't want to spend the night with alone.

Gregory Markopolis...he was an inspiration. If there is such a notion as "Gay Pride" - he was it! You don't need to flaunt it when you've got the regal poise and golden ideals of this guy. He was memorable, an impeccable aristocrat who dined at the Auto-mat (an inexpensive, now extinct, cafeteria where you put nickels into a slot to receive plates of hot food from behind glass doors.) Had he lived in another age, Gregory would have been perfectly at home in a powdered wig and buckled shoes.

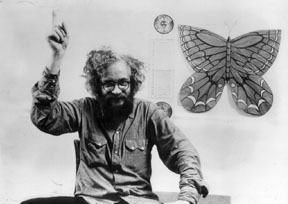

I remember you telling a story about Harry Smith hurling a brick through a plate-glass window in mid-Manhattan. Smith in fact seems to have undergone a revival of sorts - do you know anything about that?

There is a soft-cover book published about him and his working methods,

illustrated with lots of diagrams and photos. I don't have the book, but

I did get to see the  wreckage

that had once been Harry Smith, propped up by a young man, (probably a

devoted fan), volunteering as a nurse, who was escorting him down the

halls of a bohemian establishment. Old Harry's brain was by then pretty

well pickled in booze juice.

wreckage

that had once been Harry Smith, propped up by a young man, (probably a

devoted fan), volunteering as a nurse, who was escorting him down the

halls of a bohemian establishment. Old Harry's brain was by then pretty

well pickled in booze juice.

I remember once, following an 8mm show my brother and I had back in the sixties ... I had gone into the toilet of the theater to take a leak and someone else came in to do the same. "Where do you find all these people you cast for your films?" the guy standing next to me asked. It was Harry, and he seemed genuinely impressed by the population in my pictures.

The exchange we had in that tiled room was congenial, while outside in the lobby cocktails began to get distributed. I stayed a while to mingle in the lobby and then started for home. As I proceeded east on 57th street, crossing 5th Avenue, a lightweight middle aged man with long hair and thick lensed eyeglasses erupted into a berserk rampage against the "mighty establishment" that surrounded us. It was Mr. Smith, who picked up a brick from from a construction site and threw that brick through the show window of a fancy clothing store. Yes; the same Harry Smith who had spoken softly to me in the men's room had been transformed by the cocktails into "Mr. Hyde" - hell bent on destruction.

I left the scene of shattering glass and toppling mannequins before the cops arrived, and I think the Film-maker's Cooperative later bailed him out.

In the last years of his life, Harry ended up homeless and was taken in by Allen Ginsberg. Do you think America treats its Artists badly?

Harry's

condition didn't surprise me, though I didn't know Ginsberg took care

of him at the end (although Ginsberg was no stranger to the underground

film scene.) Allen Ginsberg was a fan of William Blake. He showed me the

illustrated volumes he had of Blake's on a shelf in his library. I don't

think America treats it's artists badly, its just indifferent toward them.

People are free to create - you just have to do it with your own resources.

Harry's

condition didn't surprise me, though I didn't know Ginsberg took care

of him at the end (although Ginsberg was no stranger to the underground

film scene.) Allen Ginsberg was a fan of William Blake. He showed me the

illustrated volumes he had of Blake's on a shelf in his library. I don't

think America treats it's artists badly, its just indifferent toward them.

People are free to create - you just have to do it with your own resources.

In the late sixties or early seventies, didn't you do an interview for Al Goldstein's SCREW Magazine? Did you meet Al? I didn't meet Al.

The interview was conducted by an intriguing woman named Renfu Neff, (or something like that). She had about her the glamour of an exotic, sophisticated super-model, and so my brother put her into one of his films, COLOR ME SHAMELESS, I believe. In one of those scenes where she was being man-handled by four gents in a movie theater restroom, my brother had stood up on the sink to get a better angle with his camera - the sink cracked under his weight, rupturing the water pipes into a hot and cold geyser that soaked everybody.

Film-maker Paul Morrissey was one of the key figures in the 60s underground scene - he's recently begun work on a movie that will "officially" adhere to the Dogma Principals established by Danish directors Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg. Simply by declaring his intention to do this he reaped a lot of publicity. Do you have an opinion about this much-hyped Dogma declaration, which calls for a cinema that rejects Hollywood processing and superficiality?

I've never heard of the Dogma Principal, but frankly, all movies are superficial representations of reality. The only thing that's "real" about them are the motives of the people who made them.

Could you ever imagine yourself working in the Hollywood system? Is there any joy to be had from commercial cinema?

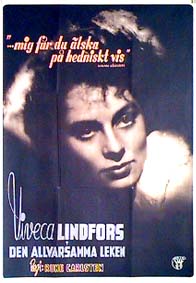

I don't have strong thoughts about working in Hollywood since I do make

my own movies. Let me tell you about the night I was invited to a dinner

sponsored by The American Film Institute. Seated next to me  that

evening was a dignified woman of dramatic stature - a lady who had been

romanced on the screen by Errol Flynn back in the thirties, and, who in

the eighties had attempted to decapitate a character played by George

C. Scott with a pair of hospital scissors. That actress, whom I've always

admired, was Viveca Lindfors (IN THE WAITING ROOM OF DEATH, BRAINSTORM,

I ACCUSE! THE DAMNED), a woman whose mere presence can elevate a crappie

flick into high class status. A conversation began between us which gained

momentum throughout the evening.

that

evening was a dignified woman of dramatic stature - a lady who had been

romanced on the screen by Errol Flynn back in the thirties, and, who in

the eighties had attempted to decapitate a character played by George

C. Scott with a pair of hospital scissors. That actress, whom I've always

admired, was Viveca Lindfors (IN THE WAITING ROOM OF DEATH, BRAINSTORM,

I ACCUSE! THE DAMNED), a woman whose mere presence can elevate a crappie

flick into high class status. A conversation began between us which gained

momentum throughout the evening.

Seems the grand lady was writing her own script and was considering using the students enrolled in her acting class at The School Of Visual Arts to act in it. To make her project feasible and affordable, she planned to use the schools 16mm camera and shoot in b&w. Now... excuse me! - but this is the same kind of "shit" I do!

Not once did she want to mention how it felt to be held in the arms of the guy who played Robin Hood for Warner Brothers, or how proud she was about playing a brain-dead patient wielding sharp shears in a sequel to the film that Linda Blair famously threw up in. We ended that memorable evening with an exchange of phone numbers as the vague prospect of me shooting her proposed production hung in the air.

She died a year later, but not before putting together her own one woman show somewhere in Greenwich Village. And somehow the idea of working in Hollywood doesn't fit anywhere in this story.

Was Catholicism a big influence on you? It seems underground cinema owes a lot to Catholicism, what with so many filmmakers trying to flush it out of their system.

My brother's brain got a bit disrupted by it, not mine. Temptation, Guilt and Redemption are themes that percolate the plots of his pictures.

... I do have a fascination for "Biblical Spectacles" - but my reasons are strictly visual. I enjoy seeing period costumes and hearing antiquated dialogue recited beneath sets that simulate polished marble. And all the bare legs that go with the times adds to the pleasure.

Bob Cowan was an active and flamboyant presence in the underground scene from early on. He acted in some of your films and also introduced you to your quintessential leading lady, a busty dance student from Queens, named Donna Kerness, (now living in San Antonio). How did you approach them as a director?

They

were both loyal troopers who I seldom "directed". I would just let them

improvise their roles and express themselves the way they saw fit for

the project, as in SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS. My philosophy was:

you start the ball rolling and everything falls into place creatively.

It was all spontaneous. The script to SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS was

being written on the spot and the ending to the picture evolved while

we were filming it. I couldn't get the ending right, so I took the whole

cast out to a restaurant, and after the meal, I knew it; the female robot

would give birth to a baby robot. The moral is, if you're ever stuck for

an answer, go out and eat well.

They

were both loyal troopers who I seldom "directed". I would just let them

improvise their roles and express themselves the way they saw fit for

the project, as in SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS. My philosophy was:

you start the ball rolling and everything falls into place creatively.

It was all spontaneous. The script to SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS was

being written on the spot and the ending to the picture evolved while

we were filming it. I couldn't get the ending right, so I took the whole

cast out to a restaurant, and after the meal, I knew it; the female robot

would give birth to a baby robot. The moral is, if you're ever stuck for

an answer, go out and eat well.

SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS was considered the "Camp Classic" of the sixties underground movement. I want to ask you about your relationship to the camp sensibility. Do you consider that film to be Camp? Camp was a sensibility that received its most publicized boost from the famous essay by Susan Sontag, "Notes On Camp" in 1964, but you seem to refer to the concept of Camp in a more geographical sense. Was Sontag's essay an influence on you?

I've never read "Notes On Camp". My own definition of the word is this: you pitch your tent (camera and crew) in an established theme-park. In the case of SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS we pitched our tent on sci-fi comic book territory and the Hollywood style of movie-making. Then you go on holiday with that established form, consciously accentuating the artificiality inherent in the styles and techniques they used to manipulate the audience. Thus the soundtrack music becomes loud and obvious, make-up is over-applied or blatantly mis-applied, and the actors are obviously "acting", or even better, they can't act at all! ... its a sort of vandalism, a form of good natured sabotage.

Were you influenced by any other Camp expressions of the day like

scopitone films,  pop

art or Maria Montez, for example?

pop

art or Maria Montez, for example?

COBRA WOMAN with Maria Montez, didn't intend to be "campy". It was a studio hack job, an assembly line product that turned out absurd, hence: humorous. "Camp" is a way of appreciating films that have just turned out wrong and are better for being so. The consciously flamboyant or "campy" stuff was done by James Whale, (THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN) and Charles Laughton (NIGHT OF THE HUNTER), both homosexuals, I think.

It seems to me that SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS was a natural progression of the kind of film you had been making since well into the fifties, and, comic books being an manifestation of Camp - well you always were a big comics book fan.

Some people are raised on the works that hang in museums - with me it was the bombastic paintings printed on the covers of science-fiction paperbacks, and the garish posters for horror movies that low-budget companies advertised as being shot in 3-D.

Do any specific comics illustrators immediately come to mind as inspirations?

Yes, Wallace Wood, who illustrated a lot of stories for E.C. "Weird Science" comic books when I was growing up in the fifties. At one point he was trying to raise money to publish an adult "Sword and Sorcery" fairy epic which he both wrote and drew, and anyone who sent him ten dollars would receive an original drawing of one of the characters in the story.

A year prior to this I had the opportunity to visit this gracious down-to-earth man when he lived and worked in a two room apartment on the far west side of Manhattan. Being an awestruck fan, I let him know what I thought and felt about his distinctive style. His work in those comic books had inspired in me a serious interest in illustrating, so I brought along a few examples of my pen-and-ink work to show him. He was particularly struck by the way I used dotted tone-sheets to form darkening shadows ominously poised behind characters. He later used this method in that epic fairy fantasy he was creating, which featured the Elf Kid he was later to send me in return for my ten buck donation, and which today I have hanging on my wall. I never imagined that I would give ideas to the "grand master of comic book thrills" who was himself an inspiration to me.

If you recall, Jonas Mekas wrote at one point that SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS was a better film than BARBARELLA, and implied that Roger Vadim might actually have swiped some ideas and scenes from SINS OF THE FLESHAPOIDS, which had previously played in Paris. Any comment?

You're

referring to the smoking finger tips in BARBARELLA, when the actors

hands touch in mock love-making, but I had sparks of lightning shooting

out of the fingers - not smoke - when the robots make love in SINS...

You're

referring to the smoking finger tips in BARBARELLA, when the actors

hands touch in mock love-making, but I had sparks of lightning shooting

out of the fingers - not smoke - when the robots make love in SINS...

Actually, anyone can steal from my movies because I neglect to copyright them, and if Vadim's screenwriters did lift ideas from my film, I can't understand why they would pass up on the idea of using comic book "thought bubbles" floating above the actors when they are required to think.

Mekas had great influence and a definite territory staked out in the underground, and a contentious relationship with other figures in the movement, like Amos Vogel. Were you ever in the "Jonas Mekas camp"? Do you ever see him today?

He wrote enthusiastically about the 8mm films my brother and I made when we had that column in The Village Voice called Movie Journal, which has since been published in book form. I appreciate the publicity he gave our work but I'm not really close to the man, although I do see him around now and then at film shows, and we sometimes do business over the phone.

Do you consider that you were ever a part of any scene or movement? While you did live in San Francisco in the seventies, it doesn't seem that you were really part of that scene, of which Curt McDowell was a key figure and which was noted for its sex-and-drug excesses.

Curt

McDowell was a desperate "Party Boy". He was driven by insatiable needs

that ate him up alive before he got old. Oh, I've had my share of sex,

but wasn't interested in drugs - that was for the younger generation to

fool with.

Curt

McDowell was a desperate "Party Boy". He was driven by insatiable needs

that ate him up alive before he got old. Oh, I've had my share of sex,

but wasn't interested in drugs - that was for the younger generation to

fool with.

And in answer to your opening question; struggling with personal demons, domesticating unbridled urges and juggling and sorting out one's ideas within the technical framework of film, in order to express a personal vision, makes you a loner embarked on a private mission, and insulates and isolates you.

I'm aware of these "scenes" and "movements" only when what I've done while I've been secluded is discovered by the movers and shakers of these movements who decide to include it into their camp.

Do you think commercial film-making ever stole or appropriated from the underground?

Once I was asked to come to a swanky office to screen some of my movies to a small but select group of advertising representatives that coldly scrutinized them. I later saw a few of my ideas pop up in TV commercials, specifically one in which a fashion model wanders through fields of tall grass, as in my film, GREEN DESIRE, where I have a bare-chested, lanky kid doing it instead. He was visceral, but the female they had was a plastic "Barbie Doll", so I didn't care, but I promised myself that the next time I'm asked to lug my films over to an ad agency, I'll make sure they pay me a fee for doing it.

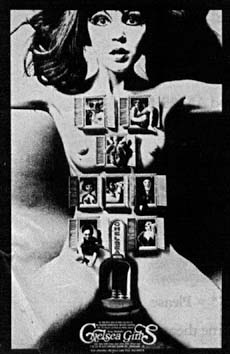

A technical question: didn't you project some of the first screenings

of Warhol's  double-screen

four hour classic from 1966, THE CHELSEA GIRLS? Did Warhol allow or encourage

the projectionist to improvise freely on sound and images changes, or

did he insist from the outset on giving specific guidelines?

double-screen

four hour classic from 1966, THE CHELSEA GIRLS? Did Warhol allow or encourage

the projectionist to improvise freely on sound and images changes, or

did he insist from the outset on giving specific guidelines?

Warhol was not the kind of person who "insisted" on anything, he always gave the impression of being detached and aloof.

Bob Cowan was the original projectionist for THE CHELSEA GIRLS, which premiered at a small theater in the basement of an office building on West 41st street in Manhattan. I was visiting with Bob up in the projection booth twenty minutes before the show when in walks Warhol with the cans of film fresh out of the lab. In a soft spoken but focused manner, Warhol suggested to Bob how the double tracks on the projectors should be orchestrated for the program. I left the booth as Bob jotted down Warhol's recommendations on a sheet of paper, and THE CHELSEA GIRLS began what was to be a long run at that theater.

I think the film was eventually blown up to 35MM for commercial release later on, and contained on one strip of 35mm film the split screen effect and sound change-overs without the need for two simultaneously running 16mm projectors.

THE CRAVEN SLUCK, from 1967, which I really love, (and which features Bob Cowan in drag) was a film that for some years you did not show. What was it that you did not like about that picture?

I had convinced myself that it was technically irresponsible and thematically shallow. You see, I was born at the end of August and branded with the sign of Virgo - I'm an insufferable perfectionist. All my films reflect me. When I see the results of what I've done with the camera, its like looking in a mirror that can become distorted by complexes I develop later on in life. Its like when you decide you are too fat or ugly or that you've talked to long on the psychiatric couch and self-loathing sets in and you start to hate yourself.

Yet I was cured of this phobia I had developed towards THE CRAVEN SLUCK when in 1996 I was invited to show it, among other films, at a number of festivals and cinemas in Europe in conjunction with the publication of your book, CAMP AMERICA. At the shows, after I timidly introduced myself and apologized for what was about to be projected, the lights went down and the screen lit up with that carefree thing I directed in my reckless youth, and suddenly all my fears dissipated - as delusions are apt to - when I realized the audience was having a hell of a good time watching it!

And while we're on the subject, I'm reminded of the time I was editing the original footage of that picture. I left the room to make a sandwich and my dog, Bocko (Star of TALES OF THE BRONX and MONGRELOID) got bored and decided to unravel a whole section of THE CRAVEN SLUCK off the reel so he could chew on it.

When I returned, I was horrified yet there was little else I could do but to eliminate what Bocko had mutilated. However this resulted in the realization later on that the movie actually worked better without those scenes, which goes to prove that there really is such a thing as "Divine Intervention".

You've said that once you paint or design a prop or a piece of background art for a film, you destroy it after the film is made because you do not wish it to exist apart from the film. Could you explain that a bit?

All that stuff was conceived to decorate another world. I don't want to own mementos looted from places where they belong and where they would be better off remaining. If they started crowding up the apartment space, I don't think I would care to see them on a screen. Movies, like memories, shouldn't be something you stumble over while on the way to the bathroom.

What are you up to these days? Do you have any new films or illustrations in the works?

I recently designed a tattoo for a fellow who plans to decorate his back with a caveman riding atop his pet Brontosaurus.

Regarding the distribution of your film work; apparently the New York Film-maker's Cooperative (175 Lexington Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016, 212-889-3820) is the only distributor of your prints in America.

Yes, they have the major films I did in the sixties. the newer ones are in a closet at home. I can usually only afford the cost of one print, so I tend to be possessive and hang onto it myself.

You've shot most of your recent work on video. Do you find the medium inferior, or even superior in some ways, perhaps, to film?

As far as mediums go, if it causes my images to move and make noise, I'll use it. And if it happens to be cheap, well, all the better! Look - my brother and I have always utilized what was considered despised and unprofessional material in our film making. We started our cock-eyed careers with the puny 8mm home movie film, and now we've come full circle back to that tiny width, only this time in video. When I was younger, I could handle 16mm equipment too, but today, not only can't I afford the outrageous price of it, I can't even lift up those metal things anymore!

In much of George's work he himself is present, a visual focus, but in your films you are almost never in the camera's eye. Do you think of yourself as more retiring, and better off behind the camera, or is it just a different approach to staging and composition? (I realize its rather pointless to compare you and George from a creative standpoint since you are different people and make different films, but being twin brothers and both film-makers, comparisons are inevitable.)

Since my films are all written, directed, lit, photographed and edited by me, they already reek enough of Mike Kuchar without the need to see the tall, balding man with the graying beard. And to tell you the truth, I prefer to distance myself from that man by representing his conflicts and desires with characters that don't physically resemble him...its less claustrophobic and easier for me to swallow that way.

Do you in any way resent the fact that George seems to have a higher public profile?

It bothers me that the scale that measures quality does not balance, and even though he's many pounds heavier than I, I'm the one who weights it down towards obscurity while his end rises up to popularity.

You've done some teaching - how do you like that? Do you find you get along easily with students?

Yes, but I get a bit uncomfortable around students who go into film-making as a stepping stone "career move" to make them rich and famous. First, you must have a love for it and be dedicated to exploring the medium. You must have a genuine interest in solving its mysteries so that you can effectively express yourself through it. Everything else that comes after is either luck or destiny.

Young people are being conditioned to pursue goals in the mega-establishment. They feel they should enter proudly into the groovy entertainment industry and make movies backed by corporations. OK...I'm living on poverty row for not selling my soul to the Devil because I've had a whiff of the mega-establishment, and man, the stench in those hellish pits made me run for the hills!

And aside from an OK paycheck that would bail me out of being broke, Film schools and Art Institutes can have sort of a stench too. The technical academies, or professionally orientated schools brainwash youngsters into obeying strict and extravagant procedural rules that dictate how movies are to be made, while the academic colleges and Art institutes function as asylums for institutionalized kids who get their creativity traumatized by pretentiously opinionated faculty members labeled "Artists" but who would be more correctly diagnosed as "Megalomaniacs", and who push an aesthetic agenda that promotes their own sense of self-importance. My advice: skip tuition and put the money into film production.

Didn't you recently direct a porno film? How did you find that experience?

I didn't "direct" it, (I'm not interested in graphic porn). I was asked to serve as cinematographer, and, like most of the jobs you loan yourself out for, it can be detrimental to your spiritual well being. You do it for the money at great personal cost, and if there is one important thing I've learned about working with so-called "Directors" of other films, its that they don't know what the fuck they are doing or how to do it!

You've also worked as cameraman on some pretty chaotic productions for other filmmakers - do you care to recall any particular horror stories, with or without mentioning names?

I'd prefer not to.

Would you describe your own temperament as placid or volatile? Have you ever "gone ballistic" on a film set or in a classroom?

No, never in a classroom where I am the instructor or on the set of one of my own pictures, but you've got to realize I've been making movies since I was eleven years old, so I don't and won't tolerate being a paid prisoner stuck on a confused set from 8 in the morning until 2 in the morning because the so-called "director" can't figure out how to shoot a ten minute scene. I'm too old for that. And how is it that these people receive huge financial grants to fumble with while I'm putting together movies with loose change?!

Yes, I have on occasion blown up on the launching pad, but with absolutely no regrets because it wasn't based on the sad fact that these people were unimaginative and didn't know their craft; it was because the problem made working conditions cruel, which gives to film-making a sour taste, and in my book that's a no no!

I recently saw one of George's videos where the two of you were all dressed up in suits and reclined in the back of a stretch limousine. It was for a John Waters' premiere I believe which he flew you both to Baltimore for. Do you occassionallly meet celebrities?

Yes, and I discover that some of them were fans of our work.

Do you feel your films can in any way be contextualized as "gay films"? Would you have any opinion, pro or con, about your work being screened at gay and lesbian festivals?

Well, I admit a lot of my film are campy (even the serious ones), and they do dish out generous portions of beefcake as dessert to complement the plots, which I suppose makes them eligible candidates. But film festivals that advertise specifics run the risk of becoming tourist traps.

My take on the whole matter is; if there's a "sticky" message to convey which has to it an insider's empathy that is open minded towards human behavior not generally accepted as being normal, then those informative insights should be slipped into a well-crafted and entertaining film unannounced so that it may go out to a more broad (and oh so "square") unsuspecting general public that won't have the chance to be scared off by labels sledge-hammed upon us by support groups.

I just wondered about the issue of context of exhibition. Where do your movies feel most at home? In a previous interview you mentioned that you feel most at home in these small theaters and back rooms with a few beat up couches and paint peeling off the walls.

Since my movies are technically small, they fit into basements that have been set up as alternative cinema clubs. I am also comfortable with store-front galleries and cozy backrooms in coffee houses that have film-night events. I once showed my films at a church in the East Village, and at a commune in San Francisco in the seventies. Because of their revered reputation, museums can be a bit overwhelming, but I certainly feel honored when those respected monuments to high culture put my movies on display so that impeccably attired patrons of the Arts can get splashed and soiled with the mud from my organic plots brewed on budgets that were dirt cheap. When you descend to gut level depths, all pretense in such a pretentious place of worships sinks and drowns.

THE END

(Jack Stevenson is a film writer, print collector and distributor living in Denmark since 1993. This year he has published books on drug and sex cinema (ADDICTED; THE MYTH & MENACE OF DRUGS IN FILM, by Creation Books, Uk, ISBN: 1840680237 and FLESHPOT: CINEMA'S SEXUAL MYTH MAKERS AND TABOO BREAKERS by critical Visions, UK, ISBN: 1900486121) and is currently working on a book about Lars von Trier.)