James Fotopoulos: An Interview

by Brian Frye

(Click here for printer-friendly version)

Brian: So, to start with, how about some background information? How did you get into film?

James: I grew up in Norridge IL, which is right outside of O'Hare Airport. It's a strange area, mainly because of the airport and the amount of activity passing through it. Combine this with the forest preserves, the factories, the hotels, and the attempt to have some type of normal suburb right on the edge of it, and it creates nothing but corrupt activity and a strange negative energy that fills the air. The area is mostly populated by suffocatingly close working class family, which would destroy your ambition and dreams if you didn't have the will power to fight the "closeness" with force. In that type of situation the standard of what you can do with your life is set very, very low. And no one wants to deal with any outside challenges or criticisms. There is a great deal of fear and threat. Fear of being exposed. But as for filmmaking, I just grew into it for reasons I can't explain. I didn't one day say, "Here, this is what I'm gonna do." My father was very interested in movies, photography, and history so maybe it comes from there. He is also very organized. My mother was always interested creating things and artistic stuff. When I was a child - in grammar school - I was interested in the filmmaking process. You know, makeup and puppets, acting these out in front of a camera and those types of things. And I was interested in still photography, drawing, science, all that stuff. And it just seemed like film - all those things were a part of it. I was into stop-motion, the Harryhausen type. I didn't know what it was at the time, but I knew I guess insinctively that those interests were fragments of this larger meduim . So, when I got into high school the obsession intensified, and I started doing video work with the high school for their public annoucements.

B: So that's when you started making moving images, in high school?

J: Yeah, when I was a freshman.

B: And that was pretty mechanical stuff, or you could do whatever you wanted?

J: No, actually I got fired.

I went to a Catholic grammar school

and a Catholic high school - they

were

private schools - basically under

the assumption that you received a

better education in a private school.

Which is wrong because anything I

learned that was useful, I learned

myself. And when I was younger, my

family and teachers at school, considered

me a troublemaker and a person of

low intelligence and with little ability.

This I think was basically because

I had no interest in school and wished

to not participate in any of it. But

now I am very glad I attended those

schools, because of the religous element

that I was able understand early on.

But in that environment you couldn't

really say, "This is what I want to

do. I want to make films," because

that was the furthest thing from anybody's

mind. Which it still is to some extent.

Even with people writing about my

films and them screening and being

distributed, I'm still, in the eyes

of many, not a "real" filmmaker. The

response to my interest to film was

very negative from many people around

me. It was perceived as a phase and

still is by some of the same people.

But this was good because I think

it forced me to be very strong-willed,

very early on. I remember that at

that time I was interested in the

Super-8 my grandfather had - he had

all the equipment - so I was leaning

toward an interest in that. And then

when I got involved in the actual

school video things, the school would

say, you know, "We're gonna do a blood

drive. Who wants to make a video for

the blood drive?" And not that many

people were really into it, I was

the only guy. And then, I would collect

my friends, and do these things. And

then I started doing stuff, ah...

were

private schools - basically under

the assumption that you received a

better education in a private school.

Which is wrong because anything I

learned that was useful, I learned

myself. And when I was younger, my

family and teachers at school, considered

me a troublemaker and a person of

low intelligence and with little ability.

This I think was basically because

I had no interest in school and wished

to not participate in any of it. But

now I am very glad I attended those

schools, because of the religous element

that I was able understand early on.

But in that environment you couldn't

really say, "This is what I want to

do. I want to make films," because

that was the furthest thing from anybody's

mind. Which it still is to some extent.

Even with people writing about my

films and them screening and being

distributed, I'm still, in the eyes

of many, not a "real" filmmaker. The

response to my interest to film was

very negative from many people around

me. It was perceived as a phase and

still is by some of the same people.

But this was good because I think

it forced me to be very strong-willed,

very early on. I remember that at

that time I was interested in the

Super-8 my grandfather had - he had

all the equipment - so I was leaning

toward an interest in that. And then

when I got involved in the actual

school video things, the school would

say, you know, "We're gonna do a blood

drive. Who wants to make a video for

the blood drive?" And not that many

people were really into it, I was

the only guy. And then, I would collect

my friends, and do these things. And

then I started doing stuff, ah...

B: Well, what kind of tapes did you make for something like that?

J: There'd be - the blood drive would come up, and there would be people vomiting, it would be stuff like that. Someone would get shot, and there would be blood all over the place, and these type of things. I guess very childish, but never trying to shock the school. I never thought of it like that.

B: Yeah, I could see the school not being particularly thrilled with that.

J: Yeah, well, they were sort of confused for awhile, but there were two teachers and one in particular that actually supported me and thought that I "had something." He is the one that told me to go to Columbia. I just fell into that school. No one in my family was really willing to give any direction or make much of an effort, so I was on my own. I was told "you have to figure out what you want to do." I knew what I wanted to do, but had to keep quiet about it for a while and just "play around" with this film stuff. Filmmaking means maybe you'll do commericals, the counselors in high school thought. So I asked this teacher, and he said "Go to Columbia. It's a good school, there's no admissions test." So from sophmore on I didn't think about college because that was where I was going to go. And maybe it is different now, but this is 1991, 1992 and the independant film phenomenon - or lie - really hadn't hit too hard yet. In Chicago at least it hit after I was gone from Columbia. I believe their admissions exploded around 1996 or 1997 and then they started going digital. But anyway, back to the videos. I did one where I think a crippled guy was in a garbage can or something like that and a Physics teacher complained. And that's when they said, "You can't do this anymore." So I was fired. So I started making videos with my friends. We started incorporating them into class projects. We did one hour and a half video of Dante's Inferno. And they actually showed those at the school. But you learn pretty quickly. But this whole time I was thinking about film from a very techincal, psychological stand point. Like, "why in this film does that shot make me feel that way? and how do you do that?" or "there are only five people in this movie's crew and the whole thing was shot outside". And very quickly you realize that film is not video, not even close - but a totally different thing. It is too bad they can't co-exist and one doesn't have to replace the other, but as we know that is not how America works. They are not interchangeable, once you begin to break down film into that emotional and technical way. This was when I was a freshman or sophomore. When I was a sophomore I shot my first film. But I was basically trying to learn the tools and what they do.

B: So you were watching a lot of film then?

J: Well, yeah. And that was all part of the learning and growing and understanding the medium. Which is still the case today. Most of it was all pretty much out of necessity. Out of understanding what you're doing in a very practical way, to get things done. So that's how I started watching a lot of films. I was interested in certain things. My dad had the International Encyclopedia of Film. I've got it right over here. You know the book I'm talking about? You know, the blue one? A lot of the avant-garde stuff's in there. And I remember that I just read through it. It went into the tinting and toning type processes, all the silents, everything was in this book. And I read through this book sort of out of curiosity. What is going on? And that just snowballed. I started watching a lot of stuff at that time. Just to understand what the history is.

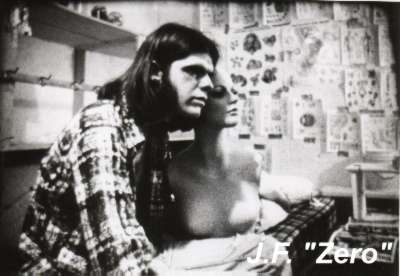

B: So your first feature was ZERO, right, but you made short films before that?

J: Yeah, I made four short films, on film.

B: In high school?

J: I made two in high school, and then I made two while I was at Columbia before I dropped out.

B: So did these first films grow out of the stuff you were seeing at the time?

J: No, I think with ZERO that was more the situation. But with those shorts I think the good thing is that I did all that when I was really young. So I had already developed an ability to organize things pretty well. Because when I would shoot these videos in high school, I would have to organize everybody, get everybody together and make them do it. And I became very good at that. Because I remember when I got into college I realized that I had - compared to the other students, I was able to pull things together quicker. And part of it was also very instinctive. I was able to just walk in and say, "This is where it goes, this is how its going to be," with a camera. And I noticed a lot of the other guys couldn't do that. I think a lot of that had to do with the fact that when I was 13 I was trying to do it. And the thing was, I was never playing around. Those videos when I was 13, I was dead serious about them. Even though looking back on them now they were probably ridiculous. But I was dead serious. This was not just me screwing off with a camera, this was real. So, even the earliest things were that way. I always acted very impulsively and instictively. And it was all very much that way. Each short was different. I remember the first short was just learning how to do things, understanding. The second was a refinement on that and with that I was very conscious of the lens and perspective, probally because of Lang's M. You know, "This lens does this, this does that." And that was done in the woods, because I grew up by a woodlands area. There were forest preserve areas by the airport. And then when I got into college I did the other one. The first one, it did well at the school. It was in that best of the year-end nonsense they do. That had the mannequin stuff in it, from ZERO. And then, the one I did after that was the sync-sound one. And by this time I did not agree with or abide by anything that they were telling me to do. I had already seen more films that any of the teachers and more importantly, shot more footage than any of them.

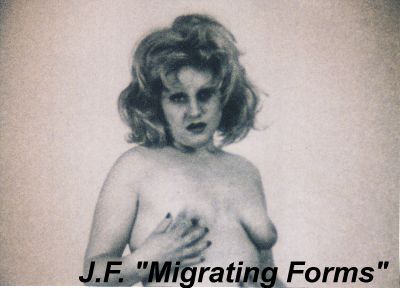

B: It's interesting that you were making these films while you were at Columbia, because especially ZERO and MIGRATING FORMS have a really distinctive stylistic quality, in terms of both the structure and this tension between a Warhol-esque documentary feeling and then these extremely distorted sequences. And I'm wondering where that came from.

J: I don't really know. I

mean, by MIGRATING FORMS, I was gone

from school. And ZERO, by the end

I was gone. The very beginning of

it I started there, but no one knew

about it, because there was so much

talk and very little productivity,

which I find embarassing. I was just

doing it outside. And I wasn't even

taking film classes. I was too fed

up even for that. I was taking a science

course, I think. Columbia was also

a complete joke. These teachers didn't

know anything. I meet teachers from

film schools all the time and I can't

believe it, I can't believe that some

of these students are taking out loans

or their parents are working two jobs,

so they can go to college and this

is what they get, and the students

don't know any better. Because the

"film world" is a very tricky and

sometimes evil place. Even at that

level. But I hadn't seen that much

experimental stuff at the time. The

majority of what I watched was studio

films. And then it was taking things

down to the very basic... ZERO came

very quickly. I wrote it out in a night.

I know now it was all serial-killer

stuff and all that, but I didn't think

of it like that. I just thought of

it very impulsively as, "What is the

extension of these types of emotions,"

and I guess it's fairly accurate in

that way. I just saw a mannequin in

a store window and the relationship

in the film came to me. And if I may

say so, there are very, very few films

I have ever seen that deal with that

subject matter properly. And sex crime,

pornography and things related are

a problem, mainly in America. I hear

people say: "We do not need any more

films about killers and hit men."

The answer to that is - you need films

that do it right. People have said

ZERO is juvenile - badly acted and

so on. The type of people in ZERO

are juvenile and their sexual obsession

with the forbidden is like a time

bomb. There is no healtly human interaction

with that behaviour. It is self destructive.

Some of them may be intelligent, but

not emotionally mature. So these people

are not reasonable, which an audience

wants. And this nightmarish existence

has to be translated into film. So

the film must mirror those emotions.

And in doing that it should be somewhat

unbearable, static, childish, externally

acted, repetitive, sterotypical, contradictory

and illogical. And in terms of "good"

and "bad" cinema, "bad" cinema is

closer to the sociopath's inner world.

People like to believe that yo can

rationalize this these actions and

behavior. But if you take your one

sexual and violent impluses and think

about from in where in the soul do

they emerge? What deep cave are they

coming from? What magic? And think

about the impluse of it, the power.

It is unexplainable in a clear cut

way. It can't be boiled down. So these

people are like out-of-control animals.

Their impluses are like time bombs,

in this quest to fillful these powerful

needs. I feel a lot of people don't

want to know that. But in terms of

the actual filming, I remember ZERO

was a learning experience, there was

an abundance of filters used, special-effects,

forced perspective, puppets, miniatures,

editing tricks. The printing was a

little insane. It was like an explosion.

This stuff was pouring out. There

was a lot of footage shot that wasn't

used. A lot of scenes that weren't

shot. But part of that was like -

you're in a situation where everyone

is telling you "you can't do all this

type of stuff." At Columbia I remember

a teacher heard I was doing this,

and he said, "It's a nice little exercise."

Because from what he saw of my shorts,

being sexual and the special make-up

and all that, to him I wasn't interested

in serious filmmaking. That type of

mentality of, "You can't do this."

So you have to develop the willpower

to do it. And that's part of the filmmaking

process, not just with the first film,

but every film. I remember with ZERO

a lot of it was making it as real

as it can be. Which I still try to

do with everything. Try to keep it

as close as I can to how things really

are. Not the lie of objectivity, which

doesn't exist or a consensus reality,

which changes, but the reality of

how we "percieve" the world.

quickly. I wrote it out in a night.

I know now it was all serial-killer

stuff and all that, but I didn't think

of it like that. I just thought of

it very impulsively as, "What is the

extension of these types of emotions,"

and I guess it's fairly accurate in

that way. I just saw a mannequin in

a store window and the relationship

in the film came to me. And if I may

say so, there are very, very few films

I have ever seen that deal with that

subject matter properly. And sex crime,

pornography and things related are

a problem, mainly in America. I hear

people say: "We do not need any more

films about killers and hit men."

The answer to that is - you need films

that do it right. People have said

ZERO is juvenile - badly acted and

so on. The type of people in ZERO

are juvenile and their sexual obsession

with the forbidden is like a time

bomb. There is no healtly human interaction

with that behaviour. It is self destructive.

Some of them may be intelligent, but

not emotionally mature. So these people

are not reasonable, which an audience

wants. And this nightmarish existence

has to be translated into film. So

the film must mirror those emotions.

And in doing that it should be somewhat

unbearable, static, childish, externally

acted, repetitive, sterotypical, contradictory

and illogical. And in terms of "good"

and "bad" cinema, "bad" cinema is

closer to the sociopath's inner world.

People like to believe that yo can

rationalize this these actions and

behavior. But if you take your one

sexual and violent impluses and think

about from in where in the soul do

they emerge? What deep cave are they

coming from? What magic? And think

about the impluse of it, the power.

It is unexplainable in a clear cut

way. It can't be boiled down. So these

people are like out-of-control animals.

Their impluses are like time bombs,

in this quest to fillful these powerful

needs. I feel a lot of people don't

want to know that. But in terms of

the actual filming, I remember ZERO

was a learning experience, there was

an abundance of filters used, special-effects,

forced perspective, puppets, miniatures,

editing tricks. The printing was a

little insane. It was like an explosion.

This stuff was pouring out. There

was a lot of footage shot that wasn't

used. A lot of scenes that weren't

shot. But part of that was like -

you're in a situation where everyone

is telling you "you can't do all this

type of stuff." At Columbia I remember

a teacher heard I was doing this,

and he said, "It's a nice little exercise."

Because from what he saw of my shorts,

being sexual and the special make-up

and all that, to him I wasn't interested

in serious filmmaking. That type of

mentality of, "You can't do this."

So you have to develop the willpower

to do it. And that's part of the filmmaking

process, not just with the first film,

but every film. I remember with ZERO

a lot of it was making it as real

as it can be. Which I still try to

do with everything. Try to keep it

as close as I can to how things really

are. Not the lie of objectivity, which

doesn't exist or a consensus reality,

which changes, but the reality of

how we "percieve" the world.

B: So was it based on something? I'm just wondering where the film came from, in terms of not just the story but also the aesthetic.

J: Yeah, I think it just sort

of came from trying to tell the truth

about those types of feelings. I think

I  had

ideas, like images of what I thought

things would be. I saw that basement

he lives in. I had seen it a long

time before. And the thing about it

is, pieces of ZERO are in those two

shorts I did. There are things that

are literally in them, like the caged

guy, the same actor, all those things.

And those feelings and images are

still there. So when the time came

to shoot it, I was translating that

into the film. Translating all of

these perceptions into the image/sound

language. Like saying, "I have these

tools that could do this and that,

and if I was in this world or parallel

worlds, how would that be in a film,

what would be the truth." And also

this is all in pursuit of a constant

pushing forward, an evolution of your

spirit. The religion of your life.

And with these tools comes a quest

to understand your relationship with

God and understand the world or worlds

we inhabit. I become very obsessive

over things and my imagination has

tendency to go into overdrive, so

I'm always trying to take all of this

chaos and control it with tools of

cinema. Like putting all this confusion

in a tunnel and contain it into something

positive. Because what you don't want

to happen is allow your imagination

to fall into depravity or laziness,

becasue that is easy to do. So your

job becomes willing your spirit and

imagination into this communication

with other people through film. People

allowing their imagination to dwell

in pornography, sexual activity and

drugs are all trying to do the same

thing I am with film: evolve to make

sense of life and understand our relationship

to God. But their way is a dead end.

Because it is easy and feels good

immediately and like anything, the

obsession is intense, but it cuts

them off from other people, from communication

with the collective, because the moral

structure of the world hasn't changed

and isn't going to anytime soon, as

long as we remain human beings, so

they remain on the outside. ZERO was

the beginning of my learning this.

But it is impossible to explain your

drive, obsession or abilities. You

can try to think about it, but you

can never understand it. It can never

be rationalized. Why images and sounds

pop into your head and why you're

compelled to make them into films,

the core of that is a mystery. I don't

think you can fully understand your

soul.

had

ideas, like images of what I thought

things would be. I saw that basement

he lives in. I had seen it a long

time before. And the thing about it

is, pieces of ZERO are in those two

shorts I did. There are things that

are literally in them, like the caged

guy, the same actor, all those things.

And those feelings and images are

still there. So when the time came

to shoot it, I was translating that

into the film. Translating all of

these perceptions into the image/sound

language. Like saying, "I have these

tools that could do this and that,

and if I was in this world or parallel

worlds, how would that be in a film,

what would be the truth." And also

this is all in pursuit of a constant

pushing forward, an evolution of your

spirit. The religion of your life.

And with these tools comes a quest

to understand your relationship with

God and understand the world or worlds

we inhabit. I become very obsessive

over things and my imagination has

tendency to go into overdrive, so

I'm always trying to take all of this

chaos and control it with tools of

cinema. Like putting all this confusion

in a tunnel and contain it into something

positive. Because what you don't want

to happen is allow your imagination

to fall into depravity or laziness,

becasue that is easy to do. So your

job becomes willing your spirit and

imagination into this communication

with other people through film. People

allowing their imagination to dwell

in pornography, sexual activity and

drugs are all trying to do the same

thing I am with film: evolve to make

sense of life and understand our relationship

to God. But their way is a dead end.

Because it is easy and feels good

immediately and like anything, the

obsession is intense, but it cuts

them off from other people, from communication

with the collective, because the moral

structure of the world hasn't changed

and isn't going to anytime soon, as

long as we remain human beings, so

they remain on the outside. ZERO was

the beginning of my learning this.

But it is impossible to explain your

drive, obsession or abilities. You

can try to think about it, but you

can never understand it. It can never

be rationalized. Why images and sounds

pop into your head and why you're

compelled to make them into films,

the core of that is a mystery. I don't

think you can fully understand your

soul.

B: Its interesting you say that, because in a way certain themes in ZERO especially, and I think MIGRATING FORMS as well, have this David Lynch feel to them, and yet the approach visually is totally different. It's got this concrete, immediate quality to the shooting. It doesn't have that otherworldly quality. It's very much in the world. Like this is actually happening. It's got a very documentary, very material feeling to what you're seeing.

J: All the stuff in the films comes from things that are around you or me. With MIGRATING FORMS, even more than ZERO, because ZERO was an outside thing. You knew the woods. You knew this industrial type basement. In ZERO you could say they came from very specific things that would happen. It's sort of like the idea of those things. The idea of a washroom. It's a private place.

B: And that was inflecting how you went about approaching the shooting of that scene then? The feeling of the space?

J: Well, the idea, which is

still an idea I have now, and I try

to adhere to, is to elevate everything

above what you're doing. You're elevating

everything to an artifice, by making

a combination of a very real physical,

concrete real object which is at the

same time artificial. By doing this,

it comes closer to our inner reality

or truth. Which film does better than

any other medium. You're taking all

of these very concrete things and

you're moving them into this inner

thing, technically, it is all done

techically, because these tools are

what is actually putting these things

up there in front of people to view.

This representation that we are all

part of this giant ball of energy

that is life. And each different tool,

will have a different effect on the

audience. It is a type of invention

or feeling or atmosphere of invention.

And I think - and I could be wrong,

but I believe - this is done in the

photography stage of the process.

It is when the camera is rolling that

this invention occurs. This aura can't

be created or "saved" later. In video,

what I believe as of now, it is done

in post. That could change for me

in the future. That is the only way

to elevate that medium into "invention"

or create that filter. Which isn't

a bad thing, just a different thing.

And that's what I was doing then,

although I couldn't articulate it.

Even in MIGRATING FORMS. The actual shooting

all comes down to being very practical.

It's supposed to be done here and

now. We have to get it done in two

days. Things build over a period of

months, and it's all very instinctual.

These pieces go together. What's important

is whether these shots fit together

or if these colors edited next to

each other make sense. For example,

a friend of mine was watching a short

film of mine and complaining that

certain shots of the film were "vagina"

references and I should cut them out.

Now many people have seen this film

and many of them have been women.

No one but him said this or even thought

this. When I explained why those shots

had to be there, why they could not

be pulled from the structure, for

many structural and textural reasons,

he just shook his head, as if that

didn't matter. But he is wrong, that

is all that matters. He projected

references onto the film from his

own personality and life history.

And that is something everyone is

going to do. You as a filmmaker can't

worry about that. It is not my problem.

You should respect your audience,

but you owe them nothing. Another

example is that someone once said

in MIGRATING FORMS that he didn't

like the film because the character

of the Man ignores the tumor on the

Woman's back. What if the Man in the

film doesn't know it is there? That

is not the logic the film creates.

Or in WALL understanding who is who

as the film progresses or trying to

hear every line of dialouge is not

the critical factor, but if the film

succeeds the dialouge and people become

an atmosphere and that feeling conveys

the meanings.That is how the film

makes sense. And people can project

any interpretation on to the film

they want, I hope they do. But that

type of thinking, that type of linear

logic, is not my interest. Because

that type of linear logic doesn't

exist in life. So the logic is the

placement or combination of the details

that create the world of the film.

Those details could be three frame

shots, shadows, lens, and so on. People

are also those details, so they too

are objects. Because the technical

stuff - whether it's video, film,

whatever - That's your representation

of your interior space. That's the

glue. So, when you're seeing the film,

it's inseperable from what you're

doing. Somebody asked me when I was

in Cleveland, "You talk a lot about

the technical stuff, what about the

content?" And I said, "There's no

difference. They're the same thing."

in MIGRATING FORMS. The actual shooting

all comes down to being very practical.

It's supposed to be done here and

now. We have to get it done in two

days. Things build over a period of

months, and it's all very instinctual.

These pieces go together. What's important

is whether these shots fit together

or if these colors edited next to

each other make sense. For example,

a friend of mine was watching a short

film of mine and complaining that

certain shots of the film were "vagina"

references and I should cut them out.

Now many people have seen this film

and many of them have been women.

No one but him said this or even thought

this. When I explained why those shots

had to be there, why they could not

be pulled from the structure, for

many structural and textural reasons,

he just shook his head, as if that

didn't matter. But he is wrong, that

is all that matters. He projected

references onto the film from his

own personality and life history.

And that is something everyone is

going to do. You as a filmmaker can't

worry about that. It is not my problem.

You should respect your audience,

but you owe them nothing. Another

example is that someone once said

in MIGRATING FORMS that he didn't

like the film because the character

of the Man ignores the tumor on the

Woman's back. What if the Man in the

film doesn't know it is there? That

is not the logic the film creates.

Or in WALL understanding who is who

as the film progresses or trying to

hear every line of dialouge is not

the critical factor, but if the film

succeeds the dialouge and people become

an atmosphere and that feeling conveys

the meanings.That is how the film

makes sense. And people can project

any interpretation on to the film

they want, I hope they do. But that

type of thinking, that type of linear

logic, is not my interest. Because

that type of linear logic doesn't

exist in life. So the logic is the

placement or combination of the details

that create the world of the film.

Those details could be three frame

shots, shadows, lens, and so on. People

are also those details, so they too

are objects. Because the technical

stuff - whether it's video, film,

whatever - That's your representation

of your interior space. That's the

glue. So, when you're seeing the film,

it's inseperable from what you're

doing. Somebody asked me when I was

in Cleveland, "You talk a lot about

the technical stuff, what about the

content?" And I said, "There's no

difference. They're the same thing."

B: One of the things that makes the films so compelling is that you don't really let this lurid subject matter overwhelm the filmmaking process. You describe the movies, and they sound as if its going to be one kind of experience, but the actual viewing is something very different. Every section of the film gets the same amount of weight. It's not like you've got a lot of throwaway and buildup, and then say "This is what I really want you to look at."

J: I think that serials from the 30's and exploitation films, horror films, and these types of cinema that are considered "low" are much closer to life. Because of the complete lack of anything that is rational and the brutality is closer to how we live. For example, I saw some lowly exploitation film recently where the hero and the heroine, bloodied and wounded from gun fire, blow up a truck in a desert with the bad guy in it. This is the end of the film. So, as this explosion is going on and they are falling to the ground arm in arm in slow motion they are making out. This may seem ridiculous, and the film was not good, but that scene most people would say "that's not realistic". But it may really be closer to life, because the rational has been stripped away and only the emotions exist. Things in my films that are considered lurid to me are never thought of that way. They are simply attempts to get close to the truth, and sometimes to get there you have to go throw some troubling things. And I again use the world I live in as my refernce point. Everything in the films is in the lives we live. Life can be very brutal. There is no need to avoid that. I don't think that art should make the viewer forget anything, but rather show people the hardness of life. And be honest about it. The films should not entertain you , but make you realize how how much potential your life has and that you could strive to accomplish great things, if you want to. Even the people in the films, they're all pieces of this giant puzzle. And all those little details matter. So if something is of a lurid nature it has to fit into the project, no differently than anything else. So the films are not just about these dark things; all elements are equal. All are part of this world. I'll be sleepless over edits. One shot will just drive me crazy for days. Every little part has to be right. Or as right as you can get it. People forget, they begin to think it's like life, where we don't pay attention to these things. But all of those little things are what make the work alive.

B: I'm interested in what you said about the people being like a piece in a puzzle. It resonates with the Chagnon film (THE AX FIGHT) that you showed at the RBMC. In a way, that whole films is about breaking down an event. Its an attempt to decipher a puzzle, as it were...

J: I think the thing that was most compelling about the Ax Fight was the idea of anthropology. The idea that we're all part of the same energy. Which I guess is there in ZERO as well. It's like the trees and all of these things are the same as we are. And they have to be given equal time. And that's not a negative, misanthropic view of people. If you take things down to the smallest particles, they're like the glue we exist in. Which is a very hopeful thing in terms of evolving.

B: That's interesting, because there is an ontological quality to all of your films. It reminds me in a way of how Bresson talks about directing. Without psychologizing. You pare things down so far. You have these extreme situations, and yet, you're not trying to present the interiour space of the characters. They're just events taking place, just like everything else. You don't try to explain them away or make sense of what they're doing.

J: The idea of the anthropologist was very strong. And that's in the studio films too. You can look at someone like Cagney - who the more I think about it, could be the best actor in the history of American films - and he existed as this thing, this block, this man, this image, and he knew it. And you don't have to go beyond that. I was talking to a guy last night about Keaton. If you look at his films - the ones that succeed - it's all action that's being filmed. It is completely kinetic things as well, which makes it come closer to a fusion of the medium and our evolving. You don't have to ask who this is, what's going on. You know. He's there and the action takes place. It's a very geometric thing. He's using these tools to explore and unearth, manipulate and record. So, I'm only filming action. I'm not filming what you're thinking. And you ask, how this relates to your own very basic existence. How is this occuring on an everyday level or in an everyday way, where I don't think about these things, because it's what I do? I don't think about a lot of what people ask me, because I'm just doing it. But I was also impressed with the idea, and I still am, and will do more with it in ESOPHAGUS. The idea of, Chagnon, going somewhere and studying something. Using these tools to try to understand things, to unearth information, to manipulate and record. He's very aware of what the tools are doing and how you can gain understanding with them. It's difficult to say, "Well, I'm going to eliminate actors." Because you can do it. You can go there, and translate it all through a camera. But to add people inside of that, you have to ask how people really act, as opposed to how movie acting is. And all these techniques and styles - avant-garde, narrative, acting and so on - are all part of the history we've made. So they need to be understood and used, and in using them, pushing forward into some type evolution of the soul.

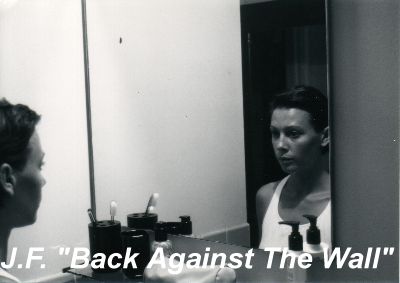

B: Maybe you could talk a little bit about your interaction with actors? In all of your films, but especially MIGRATING FORMS and BACK AGAINST THE WALL, I found myself asking, "Are these actors or non-actors?" It's hard to tell.

J: In BACK AGAINST THE WALL,

and even MIGRATING FORMS, a lot of

them had done a lot of work as actors. And my idea

was always to make it as close to

- there's all these different styles

of acting. And the more you think

about it, the more you start to think,

so what the hell is acting? It's the

same thing with photography. What

is supposed to be good photography?

I've heard two times in the last three

weeks that MIGRATING FORMS was badly

photographed. Someone said it was

shadowless. And someone else said

it was dark. That's not even worth

talking to people about, something

like that. I still have trouble understanding

what a good film is. With actors,

on a practical level, you have to

take each person individually, no

matter how many people you have. I

don't have auditions, usually I just

get to know them. You find out pretty

quickly if they're not on board, and

if so, you just lose them. In BACK

AGAINST THE WALL, the three leads

were originally all different, and

I replaced them. First, they have

to look right. They have to fit in

as a piece. They have to fit in as

an image. And the second thing is

how their voice sounds. Not necessarily

how they act, but how their voice

sounds. Then you can begin working

with them, on the basis of how their

personality is you can begin going

in and doing all this work with them.

Some need more, some less. And a lot

if it is, "Say this. More here." That

type of thing. "Sit down." To create

that blur, in between acting... in

BACK AGAINST THE WALL, when Levey

flips out it's very theatrical. But

then the rest of it is very down.

The party is acted totally differently.

And even the main girl - in the second

part her acting has changed. And that

was all very deliberate, to create

this glue of how people really might

act... How our perceptions of people

and space and objects are constantly

changing. Those perceptions change

within a blink and then we need to

assimilate these new images and actions.

When someone flips out, how do you

perceive that, if you're the person

doing it, or the person watching?

It's got to be really weird, like

a crazy thing, emotions all over.

How do you translate that into a film?

So there's always that attempt to

get the emotions of it and the atmosphere

as real as it can be, which sometimes

isn't what people think real acting

is supposed to be like. With MIGRATING

FORMS, each of those people you had

to treat differently. The main guy,

you knew he could only do this much,

that's what he was capable of, so

you worked with him in one way. The

girl internalized everything, was

more method, in a generic sense. So

that's how you worked with her, you

let her do that. The landlord was

a totally different type of actor,

he was a theater actor. So he was

this outside thing that could come

in and act very theatrically, because

he was an outside element. In WALL

it was an extension of that because

you have more actors. Debbie, who

played June in the film was a very

powerful image. Her performace is

a combination of her will power and

an understanding that she is also

an oject to be photographed and manipulated

my me. She very very interested in

everything technical and how that

was going to filter into what she

had to do. That what she was doing

was part of all these other things

that are on on the set and the filmmaking

process functions like an organism.

It's difficult to find actors like

that. The result is this strange hybrid

what we as a collective percieve as

good and bad movie acting, but that

hybrid is closer to inner truth.

lot of work as actors. And my idea

was always to make it as close to

- there's all these different styles

of acting. And the more you think

about it, the more you start to think,

so what the hell is acting? It's the

same thing with photography. What

is supposed to be good photography?

I've heard two times in the last three

weeks that MIGRATING FORMS was badly

photographed. Someone said it was

shadowless. And someone else said

it was dark. That's not even worth

talking to people about, something

like that. I still have trouble understanding

what a good film is. With actors,

on a practical level, you have to

take each person individually, no

matter how many people you have. I

don't have auditions, usually I just

get to know them. You find out pretty

quickly if they're not on board, and

if so, you just lose them. In BACK

AGAINST THE WALL, the three leads

were originally all different, and

I replaced them. First, they have

to look right. They have to fit in

as a piece. They have to fit in as

an image. And the second thing is

how their voice sounds. Not necessarily

how they act, but how their voice

sounds. Then you can begin working

with them, on the basis of how their

personality is you can begin going

in and doing all this work with them.

Some need more, some less. And a lot

if it is, "Say this. More here." That

type of thing. "Sit down." To create

that blur, in between acting... in

BACK AGAINST THE WALL, when Levey

flips out it's very theatrical. But

then the rest of it is very down.

The party is acted totally differently.

And even the main girl - in the second

part her acting has changed. And that

was all very deliberate, to create

this glue of how people really might

act... How our perceptions of people

and space and objects are constantly

changing. Those perceptions change

within a blink and then we need to

assimilate these new images and actions.

When someone flips out, how do you

perceive that, if you're the person

doing it, or the person watching?

It's got to be really weird, like

a crazy thing, emotions all over.

How do you translate that into a film?

So there's always that attempt to

get the emotions of it and the atmosphere

as real as it can be, which sometimes

isn't what people think real acting

is supposed to be like. With MIGRATING

FORMS, each of those people you had

to treat differently. The main guy,

you knew he could only do this much,

that's what he was capable of, so

you worked with him in one way. The

girl internalized everything, was

more method, in a generic sense. So

that's how you worked with her, you

let her do that. The landlord was

a totally different type of actor,

he was a theater actor. So he was

this outside thing that could come

in and act very theatrically, because

he was an outside element. In WALL

it was an extension of that because

you have more actors. Debbie, who

played June in the film was a very

powerful image. Her performace is

a combination of her will power and

an understanding that she is also

an oject to be photographed and manipulated

my me. She very very interested in

everything technical and how that

was going to filter into what she

had to do. That what she was doing

was part of all these other things

that are on on the set and the filmmaking

process functions like an organism.

It's difficult to find actors like

that. The result is this strange hybrid

what we as a collective percieve as

good and bad movie acting, but that

hybrid is closer to inner truth.

B: There were elements of MIGRATING FORMS that reminded me of both Andy Warhol's films, which people have probably mentioned, and also some on Chantal Akerman's films, specifically some of her early films, which had a very similar structure and sense of time, or time passing. Marking the passage of time through the repetition of similar sequences.

J: I still have never seen a Warhol film. Of Akerman's I've seen JE TU IL ELLE, but I can't remember if I saw it before or after making MIGRATING FORMS. The film I was watching was THE LONG VOYAGE HOME. And that was a way of communicating to the guy who was my camera operator what we were doing. He asked "What is it like?" And the atmosphere that popped into my head was THE LONG VOYAGE HOME. That was the thing that was closest in terms of grays and shadows. B: It's very common for people today to talk about post-modern directors and appropriating images, but when I see your films, I see parallels with other movies, but they don't ever feel like quotations. There are structural similarities, or sometimes even borrowed elements, but they are subordinated to the film.. It reminds you of something, but never feels like an obvious nod. I wouldn't even call them allusions so much as common approaches. J: You know I never even thought about half that stuff until someone wrote about it. Even with the makeup, which I was doing before ZERO, I just had this idea, and I had to do it.

B: It seems like a healthy form of allusion, rather than an appropriation You're making sense of certain precedents, while still keeping your distance.

J: I've never looked at someone's film and said, "Oh, I want to do that." Even people I admire, like Ford, I never said, "This is what I want to do." Even in ZERO, when I did the hand-tinted stuff, I hadn't even seen Brakhage's films yet. I had just seen silent things that were tinted, and the emotions of that made sense. You have to know about the history of film, you can't just ignore that. When I heard that in GLADIATOR they used all those polarizing filters, I wanted to go see what the hell was going down. So you want to know everything that's going on with this machine, this medium that's constantly changing. So you watch all of these films. If they creep into your work, I'm sure that happens to a lot of people

B: You write the screenplays for all of your own films?

J: Yeah.

B: So BACK AGAINST THE WALL, for instance, where did come from?

J: Well, BACK AGAINST THE WALL, that wasn't something that was sitting around. ESOPHAGUS, which I'm doing now, was a script before MIGRATING FORMS. And I couldn't get it together to pull it off. For every film you do, a whole bunch will fall through. When MIGRATING FORMS was in post, I wanted to do another film. And I tried to do this film THE NEST, then ESOPHAGUS, and another one called THROUGH THE WINDOW. WINDOW had a lot of similarities to BACK AGAINST THE WALL, the criminals and pornography and all. And is or could be if ever done a better film. I was trying to get that going, and it kept on falling apart. So, I was at a wake, and this guy was telling me, "Oh man, I have a great story, if you want to make a movie." You know, that type of nonsense you always hear, which in a way is putting you down. And it was the story of this guy who was a mechanic, and he had a friend who was a mechanic. And the guy was really intelligent, he had a very advanced comprehension. I believe what happened was he hit a guy at a stoplight or something and an argument started and he killed the other guy with a crowbar. He went to prison, and all of a sudden by coincidence, his friend was there, for a similar type of reason. And this guy read through the prision library and the two guys created a language they both communicated with. He told me the story and I was like, "Whatever, ok." But this idea made a lot of sense. These elements were playing around in combination with living in the city. Areas like Stone Park, near O'Hare and Cicero in Chicago, those areas of the city, which I always found intriguing. These very shady, red light areas where there are prositutes and all these strip clubs and fashion show bars. And there's always this undercurrent of violence in all these places, even in the clubs. The guys are drinking and the girls are around. It's very tense. Like in those little bars out by O'Hare, among the trees. And the nightclubs in the city. The way the people acting all trying to live the true American dream, which is that everyone warrents beging famous or genius.

B: Kind of lost parts of the city.

J: Yeah, lost parts where criminal behavior is going on. It's very stereotypical in one way. That does exist in a stereotypical way. And of couses these people and their behaviors are very influenced by movies and television, which feed back to that ball of energy, the glue of live, the throwing time into question and the pyschic exchange between people and object through out history. But then there's this more complex thing going on as well, this pursuit to save one's soul. And it sort of grew out of all of that.

B: In BACK AGAINST THE WALL, the guy just does what he does. There's no attempt to explain or prove his genius.

J: One of the problems is that we have these blinders on. We're always organizing everything, forming a facade, a way to deal with things. The more you get down to the smallest things, the more you realize how complex they are. And that's where understanding is. You have to be able to understand why we are, and how we're going to continue. Everyone's always trying to organize things, reduce them. There is no reason to explain. That is not where the truth is at. The truth come from how a film creates an enegry or atmosphere. And this makes the viewer active. And in that internal figuring out in combination with all experineces of your life you have brought to the film and the experinces you gain after, maybe the truth will emerge Don't get me wrong, that element of the film is important, but only what is there on the screen is necessary. Fragments of information that creates a larger world. And the more you learn about the world, the more you realize how little of it is understandable, how we are grappling with the same issues since the beginning of humans.

B: It's a rationalization. Like when someone makes a film about a serial killer, and you get the inner voice of the serial killer. Which just castrates it, because its really the filmmaker's inner voice. It's the filmmaker imagining what a crazy person is going to be thinking. And of course the filmmaker isn't crazy. So its a sane person's version of a crazy person, and all of the sudden you understand the motivation, and it makes sense. It's so dishonest.

J: Yeah, it is dishonest.

And it is part of the fear of the

idea that we are going to die. The

quest for  reason,

but with this comes a sense of meaningless

in life. So the idea is to prolong

life as long as possible and in doing

this we try to live in a "safe" world.

The war on smoking is an example and

this obsession with health. The way

digital effects are used in movies

is another example. It is a way to

not deal with the fact we are all

going to die someday. I'm not saying

that technology can't be put to some

use, but the basic ideology of simply

re-creating or re-building - not only

landscapes and fantastic creatures,

but human beings, artifacts of the

past, or actual interactions between

people and places, without trying

to shape it or push it into some type

of representation of the dream of

life - when boiled down is a way not

to deal with death. And this of course

is almost always the way it is used.

Not only in million dollar productions,

but in the avant-garde world as well.

It is a denial of the observed concrete

world that we inhabit. Because that

concrete world, which we all precieve

differently, in needed in audio/visual

to properly break through into the

parallel worlds. As is the same with

this obsession with nostalgia in not

just films today, but everything.

It is basically fear. Baby Boomers

fear they are growing old, and the

newer generations are living "virtual"

lives, so they have no real sense

of identity. All of these issues plague

the cinema, because audio/visual encompasses

it all. There are of course some great

films being made, but very, very few.

Maybe if I can keep making films long

enough or whatever film becomes in

the future, I might make some good

ones. In the films I've made, only

a few shots are any good. My palette

of tools is still very limited. You

want to create this organism of work,

that fuctions as a life. Some parts

make work and some parts may not,

some parts will be bad and some good.

But in that it mirror's one's life.

With something like BACK AGAINST THE

WALL, you have to say, "You know we

all have pieces of all of this." And

not only do we have pieces of these

people, we also have pieces of this

room, pieces of these shadows and

these sounds. Pieces of this big glue

that we all make up. If I look at

the room I'm in right now, and look

at the way it is set up, and I try

to understand why it's set this way

over the years I've lived here, it's

very difficult. I don't want to push

things under some larger umbrella,

of like "It doesn't matter who you

are, or what you are, or what orientation

you are, or anything. You fall under

this umbrella." The artifacts from

previous civilizations are what we

have to work with. And those need

to be pushed ahead, to be comprehended.

But to do that, you have to tear away

all of the rational things you've

set up. So there's that. Then you

have to remove this handed down type

of filmmaking- When I was in Arizona,

and these guys from AFI made this

film. The things was like ten minutes,

with crane shots. It was insane. Tom

Hanks's brother was in it.. And they're

up there just talking about how hard

it was, how defeated they were, about

the rain. And that's just handed down.

They're supposed to think that. They've

been given the filmmaker's badge of

problems. And that doesn't help anybody.

It doesn't have anything for others.

reason,

but with this comes a sense of meaningless

in life. So the idea is to prolong

life as long as possible and in doing

this we try to live in a "safe" world.

The war on smoking is an example and

this obsession with health. The way

digital effects are used in movies

is another example. It is a way to

not deal with the fact we are all

going to die someday. I'm not saying

that technology can't be put to some

use, but the basic ideology of simply

re-creating or re-building - not only

landscapes and fantastic creatures,

but human beings, artifacts of the

past, or actual interactions between

people and places, without trying

to shape it or push it into some type

of representation of the dream of

life - when boiled down is a way not

to deal with death. And this of course

is almost always the way it is used.

Not only in million dollar productions,

but in the avant-garde world as well.

It is a denial of the observed concrete

world that we inhabit. Because that

concrete world, which we all precieve

differently, in needed in audio/visual

to properly break through into the

parallel worlds. As is the same with

this obsession with nostalgia in not

just films today, but everything.

It is basically fear. Baby Boomers

fear they are growing old, and the

newer generations are living "virtual"

lives, so they have no real sense

of identity. All of these issues plague

the cinema, because audio/visual encompasses

it all. There are of course some great

films being made, but very, very few.

Maybe if I can keep making films long

enough or whatever film becomes in

the future, I might make some good

ones. In the films I've made, only

a few shots are any good. My palette

of tools is still very limited. You

want to create this organism of work,

that fuctions as a life. Some parts

make work and some parts may not,

some parts will be bad and some good.

But in that it mirror's one's life.

With something like BACK AGAINST THE

WALL, you have to say, "You know we

all have pieces of all of this." And

not only do we have pieces of these

people, we also have pieces of this

room, pieces of these shadows and

these sounds. Pieces of this big glue

that we all make up. If I look at

the room I'm in right now, and look

at the way it is set up, and I try

to understand why it's set this way

over the years I've lived here, it's

very difficult. I don't want to push

things under some larger umbrella,

of like "It doesn't matter who you

are, or what you are, or what orientation

you are, or anything. You fall under

this umbrella." The artifacts from

previous civilizations are what we

have to work with. And those need

to be pushed ahead, to be comprehended.

But to do that, you have to tear away

all of the rational things you've

set up. So there's that. Then you

have to remove this handed down type

of filmmaking- When I was in Arizona,

and these guys from AFI made this

film. The things was like ten minutes,

with crane shots. It was insane. Tom

Hanks's brother was in it.. And they're

up there just talking about how hard

it was, how defeated they were, about

the rain. And that's just handed down.

They're supposed to think that. They've

been given the filmmaker's badge of

problems. And that doesn't help anybody.

It doesn't have anything for others.

(Editor's Note: For more information on Mr. Fotopoulos , be sure to visit his website: http://www.fantasmainc.com/)