New Babylonians: Contemporary Visions of a Situationist City

A Review by David Cox

(Click here for printer-friendly version)

New Babylonians: Contemporary Visions of a Situationist City by Iain Borden (Editor), Sandy McCreery (Editor) Paperback - 112 pages (August 10, 2001)

John Wiley & Sons; ISBN: 0471499099

The

book is a unique combination of essays

and articles about the enduring influence

of the Situationist International

on contemporary ideas about urban

planning and architecture. I am happy

to see this publication, dovetailing

as it does with my own research interests

into electronically mediated urban

space. At $61, its price tag is high,

and it fits neatly into that category

of book which is part coffee-table,

part research document, part magazine

which the Architecture and Design

industries love to produce. These

documents are made to feel valuable,

and this one does.

The

book is a unique combination of essays

and articles about the enduring influence

of the Situationist International

on contemporary ideas about urban

planning and architecture. I am happy

to see this publication, dovetailing

as it does with my own research interests

into electronically mediated urban

space. At $61, its price tag is high,

and it fits neatly into that category

of book which is part coffee-table,

part research document, part magazine

which the Architecture and Design

industries love to produce. These

documents are made to feel valuable,

and this one does.

The work is a timely and excellently thought out text, which is likely to enter the growing canon of key texts on the subject. Arguably the most important of these is Simon Sadler's "The Situationist City" which spent the first chapter apologizing for being academic, before declaring itself so; hoping to pre-empt the protests of the pro-situationists out there. The situationists of course themselves hoped to pre-empt any criticism of their movement as just another 'ism' by declaring "there is no such thing as Situationism".

I was most impressed with the reprinting of the original "New Babylon: An Urbanism of the Future" article in the 1964 issue of Architectural Design by the genius architect and visionary Constant Nieuwenhuys. Constant's relentless and breathless exaltations to a world of free play and creativity are evocative and compelling:

The Homo Ludens of the future Scotty will not have to make art, for he will be able to creative in the practice of his life. He will be able to create life itself and shape it to correspond with still unknown needs that will emerge only after he has obtained complete freedom.

The

city proposal which Constant put forward

as the physical expression of his

utopia of free play bears striking

resemblance in parts to representations

of the Internet, (those mad tapered

spaghetti lines pouring out of cities

representing bandwidth and 'net traffic)

in books such as "Mapping Cyberspace".

Assembled using perspex and bike parts,

the models Constant built and the

diagrams for New Babylon reflect a

desire to see the future city as a

negotiable, plastic, ever changing

carnival of celebration. A kind of

leisure and good living festival which

never ends. Connecting wires and poles

suspend circular transparent layers,

connected by ramps and walkways. New

Babylon looks like a kind of organism

of tensile delicacy. In Constant's

own words:

The

city proposal which Constant put forward

as the physical expression of his

utopia of free play bears striking

resemblance in parts to representations

of the Internet, (those mad tapered

spaghetti lines pouring out of cities

representing bandwidth and 'net traffic)

in books such as "Mapping Cyberspace".

Assembled using perspex and bike parts,

the models Constant built and the

diagrams for New Babylon reflect a

desire to see the future city as a

negotiable, plastic, ever changing

carnival of celebration. A kind of

leisure and good living festival which

never ends. Connecting wires and poles

suspend circular transparent layers,

connected by ramps and walkways. New

Babylon looks like a kind of organism

of tensile delicacy. In Constant's

own words:

The unfunctional character of this playground-like construction makes any logical division of the inner spaces senseless. We should rather think of a quite chaotic arrangement of small and bigger spaces that are constantly assembled and dissembles by means of standardized mobile construction elements like walls, floors and staircases. Thus the social space can be adapted to the ever-changing needs of an every changing population as it passes through the sector system.

He could have been talking about the world wide web. He could have been talking about the types of structures which emerge out of the anti-globalisation movement - provisional, functional, short term, but dedicated to social change and emblematic of ongoing struggle with the creative spirit as its engine. .All those large street puppets, bikes and buses retrofitted with media equipment, independent media and ideas fueling a new type of city; post industrial, post capitalist, post work.

This is city as collage, also celebrated by the much less politically motivated Archigram group in the UK, key members of which now design massive architectural features for megaband stadium concerts. In our era of continuous connectivity and onion-skin-like layering of urban culture with invisible digital sheets of communication, the need to understand the city as a place beyond work and production would appear more an issue than ever.

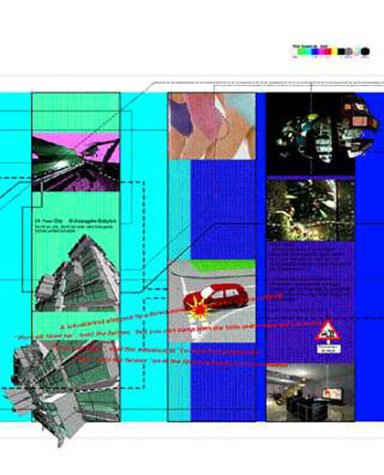

The

book features also some superb anti

capitalist collage by the General

Lighting and Power group, whose slick

mock-advertising images of soft focus

female forms in leotards and computer

graphics of office interiors and car

accidents are intersected every-which

-way by droll pseudo situationist

aphorisms such as:

The

book features also some superb anti

capitalist collage by the General

Lighting and Power group, whose slick

mock-advertising images of soft focus

female forms in leotards and computer

graphics of office interiors and car

accidents are intersected every-which

-way by droll pseudo situationist

aphorisms such as:

"Aerobics is necessary: progress implies it" ("I see you baby, shaking that ass")

and

"God is in the retailing"

This stuff reads like Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger with a laugh track. It helps if you know something about the spirit of the Situationists and their love of reverse engineering the information environment to fully understand the wicked humour of this section.

Of particular interest is an essay on the similarities between the Situationist's idea of the 'derive' (essentially navigating a city for purposes other than those officially ascribed) and the experience of using the internet. In a first class comparison between S.I.'s project for a work free society and the world wide web, Colin Fournier, architect and educator makes some keen observations. It turns out that many of the characteristics of the web mirror attributes the S.I. Considered prerequisite for their utopia: an ephemeral, negotiable type of city, where uses were determined by the population, surfing the web is like the idea of drifting or deriving through a city. Both the situationist city and the web share the qualities of flexibility, dynamism. They are naturally and in keeping with their design open to use for play and social experiment.

Another essay covers the 'repurposing' of Berlin into a zone for free wandering. A man distributes maps to a formerly divided area of Berlin, and encourages participants and passers by to follow prescribed pathways on these maps, despite the fact that often the lines to be followed are barred by walls, gardens and other impediments. This is the diary of an Abstract Tour Operator. Like the old Surrealist idea of using a map of one city to find one's way around another, this project fuses two cities, or rather the multiple cities of Berlin in the minds of all who live there. It grabs people off the street, gives them a map and tells them to get lost. Literally.

The byline reads:

Paralells can be drawn between the manoeuvres or guided walking tours executed by the artist Tim Brennan and the derives or drifts of the situationist project. Similarly Brennan seeks to raise consciousness and 'speak' to his participants thought his tours, which combine highlights of 'ideologically unselfconscious phenomena' with 'bodies of preexisting information'.

A chapter written by Charles Rice looks at the massive billboard signs which are proliferating in major cities, arguing that "these spatial fantasies effectively deliver identification with the disant and the unattainable" to quote the byline.

These imposing wall-signs literally occupy the sides of skyscrapers, and in most cases offer ways to reimagine the city as re-scaled 'events'. One example is the side of a New York building which has been turned into a vast bookshelf. I'm not sure I buy Rice's flip observations about "The Space of the Image" - they sound too much like apologia for the design principles behind what are essentially ugly big ads, refusing to be ignored. These billboards represent the symbolic penetration of corporate culture to the city level, and in re-scaling massive buildings, seem to indicate that the playfulness which the Situationists assumed would fall into the population's hands, is now firmly in those of global commerce no hence longer playful, just banal and obvious.

I

doubt SI themselves could have themselves

produced this book, it takes too historical

a view, and treats the movement of

Guy Debord and Constant and the others

way too much like a startlingly unlikely,

but welcome curiosity of history.

This said, the book does look vaguely

like something the SI might have released.

This is only relevant as the SI were

well known for their self-published

texts, such as Potlach and the Situationist

International. The book has the look

and feel of something being proposed,

like a call-to-action style activist

pamphlet on steroids. Part of me thinks

of it as just a bit too slick, too

overproduced, too radical chic. Debord

would probably have dismissed its

sensible well-designed Photoshop and

Illustrator layout as haplessly specialist.

Possibly even 'spectacular'. Then

again he could have read every page

front and back and put it up there

with all the other successes he and

his movement can claim for themselves.

I

doubt SI themselves could have themselves

produced this book, it takes too historical

a view, and treats the movement of

Guy Debord and Constant and the others

way too much like a startlingly unlikely,

but welcome curiosity of history.

This said, the book does look vaguely

like something the SI might have released.

This is only relevant as the SI were

well known for their self-published

texts, such as Potlach and the Situationist

International. The book has the look

and feel of something being proposed,

like a call-to-action style activist

pamphlet on steroids. Part of me thinks

of it as just a bit too slick, too

overproduced, too radical chic. Debord

would probably have dismissed its

sensible well-designed Photoshop and

Illustrator layout as haplessly specialist.

Possibly even 'spectacular'. Then

again he could have read every page

front and back and put it up there

with all the other successes he and

his movement can claim for themselves.

These issues matter less and less, as one realises that no matter how many glossy attractive and expensive books come out based on S.I. ideas 'revisited", the Situationist International has successfully avoided having been too neatly encapsulated in history and academicism. It will be a while yet, though hopefully not too long, before those in a position to do so implement anything like the vision of New Babylon and the type of Permanent Autonomous Zone it embodies. A permanent 'Burning Man' festival. A paradise for the nomadic, an oasis of free play and the free imagination, unshackled from the drudgery of contemporary capitalism.

These ideas get inside your head, like psychic Palmolive (you know you're soaking in it!) I've been picking this book up and reading it for days now. It has become an addition to my daily routine. I recommend it highly for anyone interested in Situationism, Utopia, or the idea of society where work, rules and authority are a thing of the past. And given the times we live in, is not that just about everyone these days?

David

Cox

Lecturer

in Digital Screen Production At Griffith

University

School of Film Media and Cultural

Studies

email: d.cox@mailbox.gu.edu.au

personal web site: http;//www.netspace.net.au/~dcox/dcox.html