“BEAUTIFUL TROUBLE: A Toolbox for Revolution”

Assembled by Andrew Boyd and David Oswald Mitchell

New York, London: O/R Books, 2013 (in several versions for the reader of today)

Reviewed by Molly Hankwitz

“Human salvation,” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. argued, “lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.”

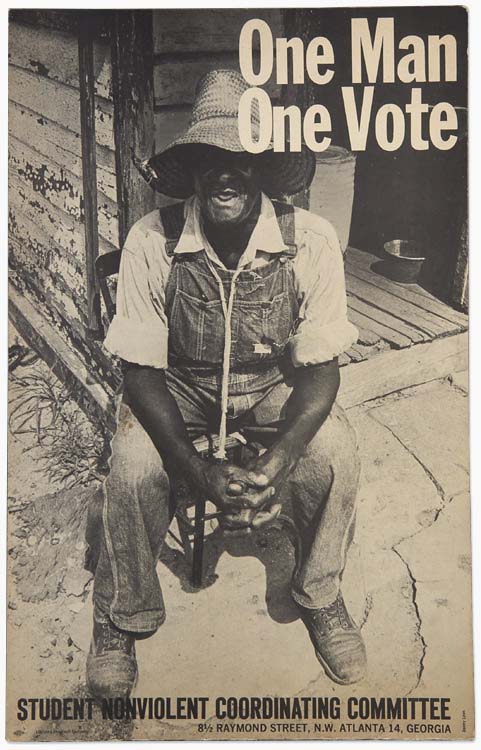

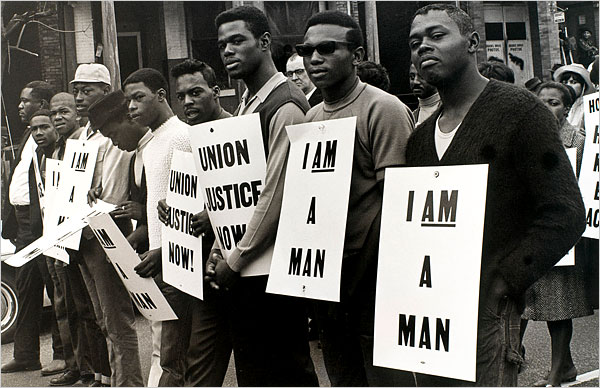

King’s protest culture—the culture of the non-violent Civil Rights movement—when examined in historical hindsight is a movement of songs, placards, banners, signs, people sitting-in, marching, chanting, and making speeches. The Civil Rights movement was about people building power against the racism afflicting African-American populations, about the dignity of the working poor and Labor itself. It was about the organized power of people to righteously commit to a cause and use a collection of strategies to produce their dream of racial equality. In this context, the Civil Rights movement utilized social “technologies” to act as conduits of information flows between themselves, their supporters and “the media”: music, word-of-mouth, “phone trees,” pamphlets, buttons, face to face meetings, print journalism, articles, the occasional mainstream radio (or even TV spot), and the free(r) press were but some of the means.

Old and New Tactics and Technologies in Media Activism

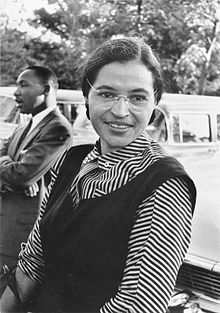

“Creative maladjustment” is a form of media activism, one could argue, if it brings about public commentary and social change. It could be used, in this way, to describe the work of black women who had been arrested for refusing to budge on public buses, including the well-known, Rosa Parks, who, though operating as a private citizen in her arrest, had been trained for activism at the Highlander Folk School, a center for political activism, in Tennessee. Parks’ action was supported by the powerful NAACP, contributed to the Montgomery bus boycott and eventually to the full legal desegregation of public buses.

When the participation of white college students or journalists in these protests lead to disappearance or death, northern newspapers and television news broadcasts started to report.

Large scale marches and violent riots reached newsrooms (and thus thousands of American homes via TV and radio broadcast) while an increasingly efficient long-distance post-war telephone system– seen specifically with the development of switchboards and handsets– laid the infrastructure for organizing and proliferating political resistance throughout the nation.

In the late 90’s and early 2000s, the anti-globalization movement was hot, but since has gradually decentralized and largely dissipated. Activist “burn out”, increasingly violent state response, well-armed, well-protected riot police, and a few deaths slowed what had been a strong and organized wave of political dissent from Jakarta (J8) onward.

However, in Seattle in 1998, barriers of time and space were broken by media activists. Daily alternative cable television broadcasts in the United States of “The Battle for Seattle”, the Indymedia citizens’ journalism phenomenon, and ultimately, the stopping of the planned WTO meeting, meant that revolution had taken a new turn. The Internet, cable, and satellite technologies made a world of radical, non-corporate or commercial minded media innovation possible.

Where is Media Activism Now?

Today, we are inundated by the hyper-mediation of daily life. So persistent is the chaos of capitalist consumption that our efforts to access meaning are labyrinthine. In the urban centers of western capital, the Monoculture tries to colonize and define our Time. Yet, Occupiers have recently awakened the potentials for revolutionary mass culture from their dying embers. Occupy reframed solidarity and rejected both the unethical bank crimes of Bush era empire as well as the perpetuation of “just war.” Occupy also built online and offline communications networks and succeeded in drawing attention to the specificity of the confrontation, that being the means and methods of a transnational capitalist upper-most class thriving on the exploitation, control, and total surveillance of working-class populations.

We’re Here

BEAUTIFUL TROUBLE articulates the most recent tactics and strategies of The Occupy Decade. It adds to a reactivation of protest culture by offering a contemporary, accessible, and successful integration of revolutionary history and future potentials for political engagement. It is a righteous compendium, a desktop reference/handbook informed by historical struggle, trial and error, and tactical revolutions of the 21st century, from Egypt to Greece to Syria to Wall Street. This book is assembled like one giant collaborative blog or wiki, but in print, with an affordable e-book form and backpacker’s “pocket” paper edition. It is designed for distribution. It is philosophically “open” and eminently useful like a piece of good freeware. Readers can choose from quick tips and complete well-calculated strategies, or sit back and check out the brief and plucky “how-to’s” with theoretical input from 21st century revolutionaries. Pages are clearly laid out for photocopy machines, and so functions as “less a cookbook” than a “pattern language” for suggested action. [i]

In it are voices from labor movements, anti-war activism, queer activism, and others, collectively celebrating the victories and recent social history of the ‘anti-globalization’ and Occupy movements. Moreover, BEAUTIFUL TROUBLE aspires to the healthy, psychic energy that arises when failure is met with humor, and power is met with surprise, that moment when “pre-figurative intervention” is used “to give a glimpse of the Utopia we’re working for, to show how the world could be; to make such a world feel not just possible, but irresistible.” (p. 39, pocket edition).

BEAUTIFUL TROUBLE lays out the core tactics, principles and theoretical concepts that drive creative and utopian activism, providing analytical tools for change makers to learn from their own successes and failures. In the modules that follow, they map the DNA of these hybrid art/action methods, tease out the design principles that make these methods tick, as well as the theoretical concepts that inform them, and then show how all of these work together in a series of instructive case studies.

In its effort to make activist vocabulary less old-school and more contemporary, fun, and sexy, this book is a milestone of cultural dissent. The editors include a universe of interventions and tactics now required by us in order to combat technocratic social contro—from the antics of famous culture jammers, The Yes Men—to organizing principles of labor unions and street theater activists.

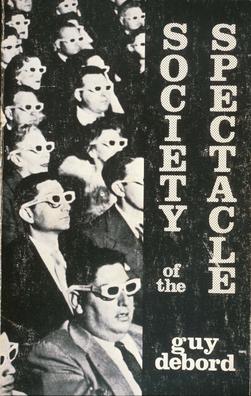

Cover of Debord’s famous pamphlet.

It offers serious organizers, wannabe pranksters and radical politicos a coherent aesthetic and plausible backdrop for revolutionary action. However, emphasis upon “the event” is troubling precisely because we are left without much discussion, if any, of how to reach and bring in –not simply those with the media power—but those for whom “empowerment” may yet to be realized, and for whom exclusion has become normalized.

Two very important questions remain: What exactly is the so-called Utopia “we’re working for” and who are “we”?

Notes:

[i] The originator of the concept of a pattern language, architect Christopher Alexander, introduces the concept thus: “… the elements of this language are entities called patterns. Each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.” Alexander first introduced the concept of pattern languages in his 1977 book A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, in which he sought to develop “a network of patterns that call upon one another” each providing “a perennial solution to a recurring problem within a building context.”

Links:

http://www.appliedautonomy.com/

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/21/arts/design/21civil.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0