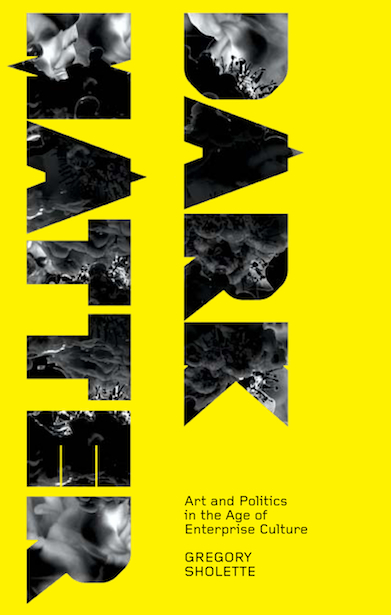

Finally, a history of collective precarity from a politicized artist. Author/writer Gregory Sholette, in the final paragraph of Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, at last clarifies the frequently cited metaphors of “zombies” and enormous digital casts, with which the likes of Annalee Newitz have been preoccupied in terms of popular culture, and most notably, the big-budget-extravaganza digital films of recent decades. He writes:

Finally, a history of collective precarity from a politicized artist. Author/writer Gregory Sholette, in the final paragraph of Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture, at last clarifies the frequently cited metaphors of “zombies” and enormous digital casts, with which the likes of Annalee Newitz have been preoccupied in terms of popular culture, and most notably, the big-budget-extravaganza digital films of recent decades. He writes:

We go on picking the rags, but every now and again, this other social [non] productivity appears to mobilize its own redundancy, seems to acknowledge that it is indeed just so much surplus—talent, labor, subjectivity, even sheer physical-genetic materiality—and in so doing frees itself from even attempting to be usefully productive for capitalism…, though all the while identifying itself with a far larger ocean of “dark matter,” that ungainly surfeit of seemingly useless actors and activity that the market views as waste, or perhaps at best as a raw, interchangeable resource for biometric information and crowdsourcing. The archive has split open. We are its dead capital. It is the dawn of the dead.

This blatant appeal to the use-value of our necrophilia, artistic waste, and the products of our labor and time runs throughout an historical text, alternately conscious of its own limitations and brilliantly pervasive in its political critique and arts research. Sholette devotes himself to describing the animation of a diverse selection of contemporary artists’ collectives and collective projects—American, European, South American, and “other”—for whom relationships, as cultural workers to the neo-liberal art world in the recent decades of the 21st century, have been a central concern. Among this history are crisp critical frameworks for understanding art and its positioning against what he calls “enterprise culture,” or the current era of marked precarity in which artists are force to live, which is also marked by “enforced creativity” imposed on all forms of labor.

Sholette, a New York-based artist, writer, and founding member of Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D: 1980–1988) and REPOhistory (1989–2000) is as engaged a political critic as he is an artist/activist. “Dark Matter” is a considerable art and activist history contributing an elegant read to what is already in print while paying homage to such luminaries as Lucy Lippard and Martha Rosler, lurching forward, afresh in its sharp critique of the neo-liberalization of daily life, and celebrating collective action in the “art world.”

Much published history around activist art falls into two camps: books on specific “identity politics” art from feminists, gays, Latinos, “etcetera” artists: David Roman’s Acts of Intervention: Performance, Gay Culture, and AIDS, for instance, and Street Art San Francisco: Mission Muralismo, by Annice Jacoby, for another; and movement-oriented art books highlighting one “outsider” art form—graffiti, stencil art and Occupy art, for instance, which bracket a specific local/global analysis; or art, comix, photography, music, and poetry “output” of a single movement. Then there are publications which recuperate material archives as political art history: posters, papers, ‘zines, and self-made/artists’ publications from collectives and groups. George Kaplan’s newly edited book, Power to the People! is a recent manifestation. Both publishing directions offer significant breadth of understanding to radical culture and political art. To understand what Sholette’s book has to offer readers—as a companion to these kinds of texts—is to reflect fully upon his politics around collectivized art in contrast to the “enterprise culture.” He frames his position within a discourse on surplus labor and “the invisible mass,” privileging the radical economy behind interventionist works as the basis of an era of art-making outside the mainstream. In other words, this book is about radical art now; not recuperated art, and it is about strains of art practice which would elsewise go unnoticed, particularly in the broad, totality of culture on which he writes.

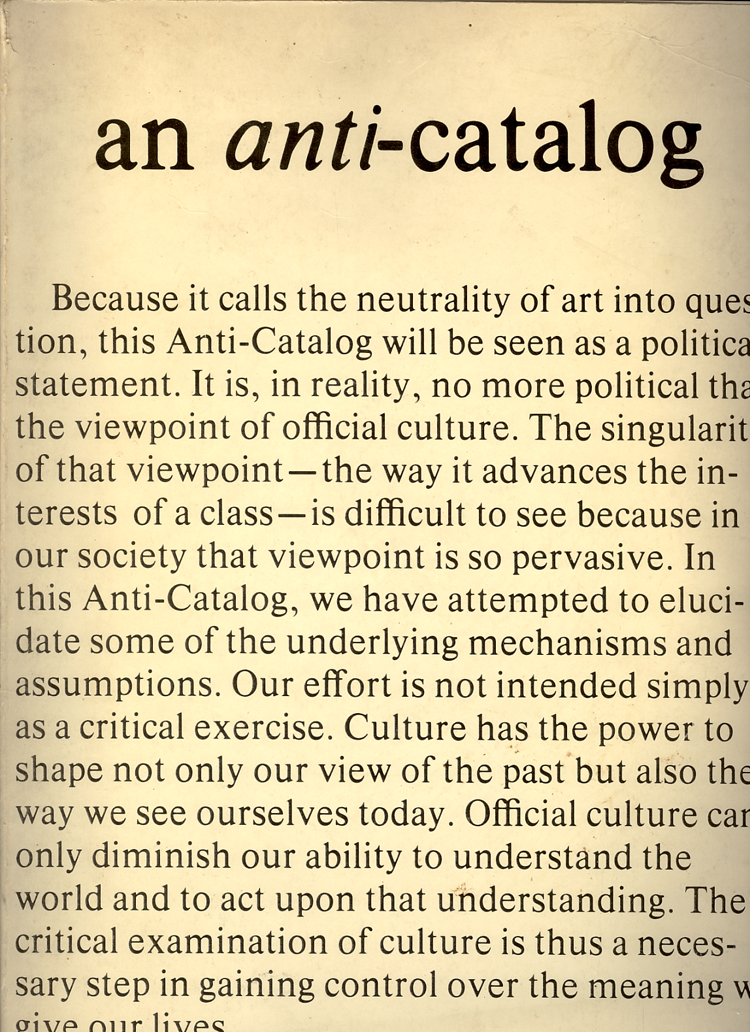

“an anti-catalog”: A Response to the exhibition “American Art,” Whitney Museum of American Art, 1976; collection of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller; 3rd Artists Meeting for Cultural change, 1977.

On one level Dark Matter is a critique of the “clipping out” of particular activist art for curatorial shows, that removes the work from its labor, and reduces it to a mere “institutional” appropriation. His discussion of “counter-institutional” interventions is a finely-tuned account of political-art production by contrast. Sholette makes the sophisticated argument that precarity, while not desired, is its own best motivator. Useless labor—cast out and obscured as a byproduct of neo-liberal capital—develops its own economy from which to persist, linking methods of making art as social production to itself as a product of its own circumstances, much like the aesthetics of Arte Povera or feminist rejection of art history, which presumed male-dominated creation, materials, and subjectivities of high art and reflected the politics of art processes, hierarchies, and so forth.

Sholette’s pursuit of these ideas is fresh, intelligent, particular, and funny. He asserts what he investigated in a previous book, Radical Social Production and the Missing Mass of the Contemporary Art World (Pluto Press, UK, 2009), in which he examined the “social production” of art and the transition from “modernity” (which presupposed public spheres and “masses”) to contemporary culture. His objective there was to locate the mass, strategically and politically, and to name its purpose in the capitalist and artistic imaginary. In “Dark Matter,” he looks again at “invisible” (or the missing) contemporary artistic work amidst today’s neoliberal appropriations culture, where its networked machine sucks up everything up for its own use. This is a central and important visualization of the current ground upon which politicized art stands. As “dark matter,” in contrast to that upon which light is shed, it has a certain material power. The “missing mass” imaginary of networked communications, creative industries, and immaterial culture is thus reassembled as a perceptible class of cultural workers. This is fantastic, like Bridle’s corollary imagery of virtual subjects wandering in as-yet-unbuilt architecture in his talks on “New Aesthetics.” Sholette points, in this assertion, to the manner by which the white electronic computerized screen blinds us to the material, and forces imaginaries upon us. This has not been stated so well by any other writer.

A Users Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life (with Nato Thompson for MassMoCA/MIT Press, 2004, 2006, 2008), as well as a special issue, “Whither Tactical Media?,” of the journal Third Text (co-edited by Sholette with theorist Gene Ray) deal with some of these ideas as well. Dark Matter is a comprehensive guidebook to collectivized, politicized art in contemporary times.

www.gregorysholette.com

www.darkmatterarchives.net

NEED a copy of this. I’m especially curious to see what Sholette has to say about where usefully politicized art begins, what form it might take, and the form of the impression neoliberal appropriations culture leaves upon this “invisible” contemporary artistic work in question– in other words, how might politicized art, despite (or perhaps due to) its invisibility effectively react to such an appropriations culture, especially in a world in which appropriations culture inevitably intervenes? Can’t wait to read further!