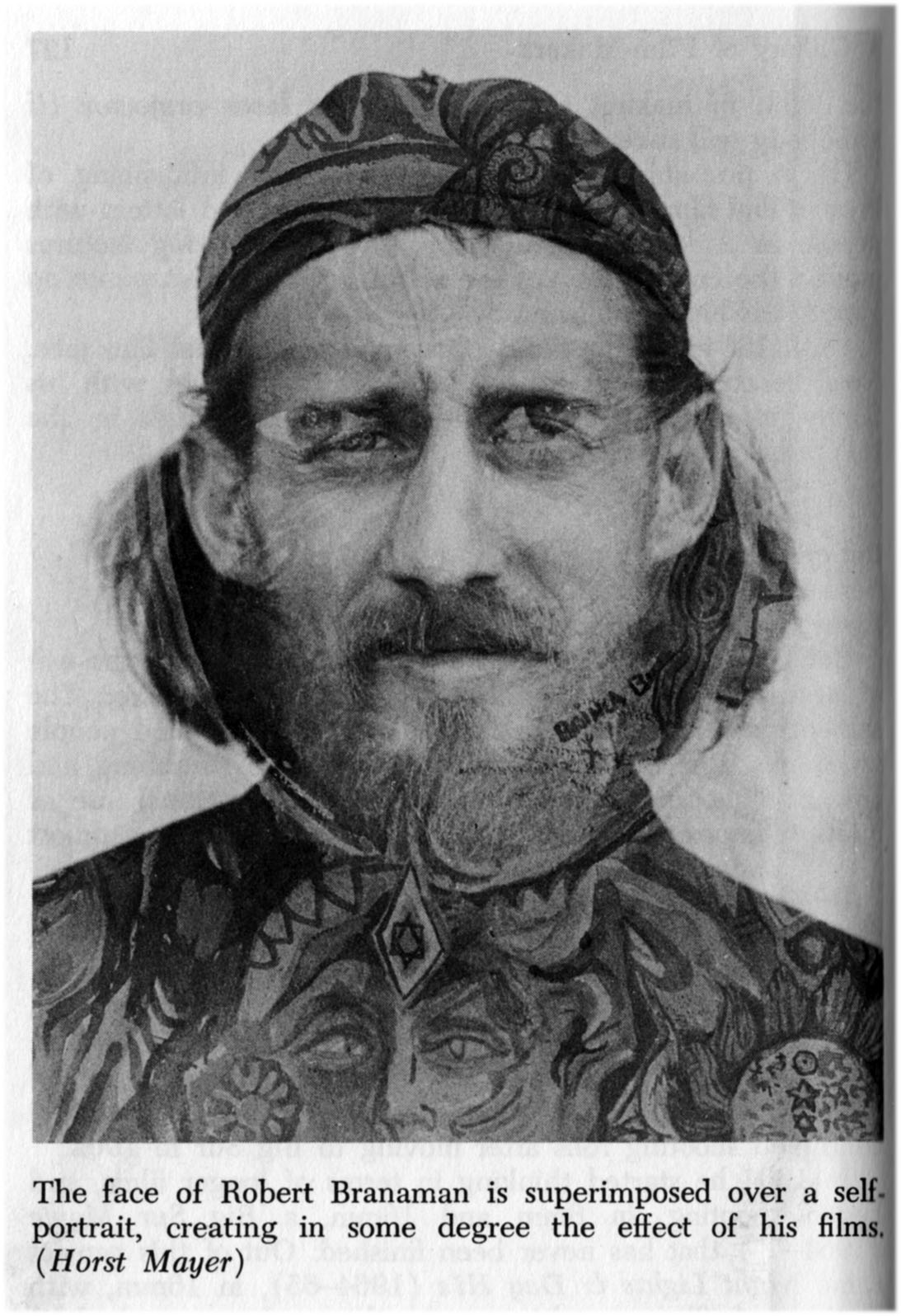

The Spring 2011 Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area series at Pacific Film Archive included both in its screenings and the accompanying exhibition catalogue the work of Robert Branaman, a Beat artist now nearly 80 years old. Still, the book had nothing really to say about Branaman’s work, other than his associations with Bruce Conner and Stan Brakhage. I propose to examine his work more closely to assess why he was included as an important Bay Area filmmaker.

The Spring 2011 Radical Light: Alternative Film and Video in the San Francisco Bay Area series at Pacific Film Archive included both in its screenings and the accompanying exhibition catalogue the work of Robert Branaman, a Beat artist now nearly 80 years old. Still, the book had nothing really to say about Branaman’s work, other than his associations with Bruce Conner and Stan Brakhage. I propose to examine his work more closely to assess why he was included as an important Bay Area filmmaker.

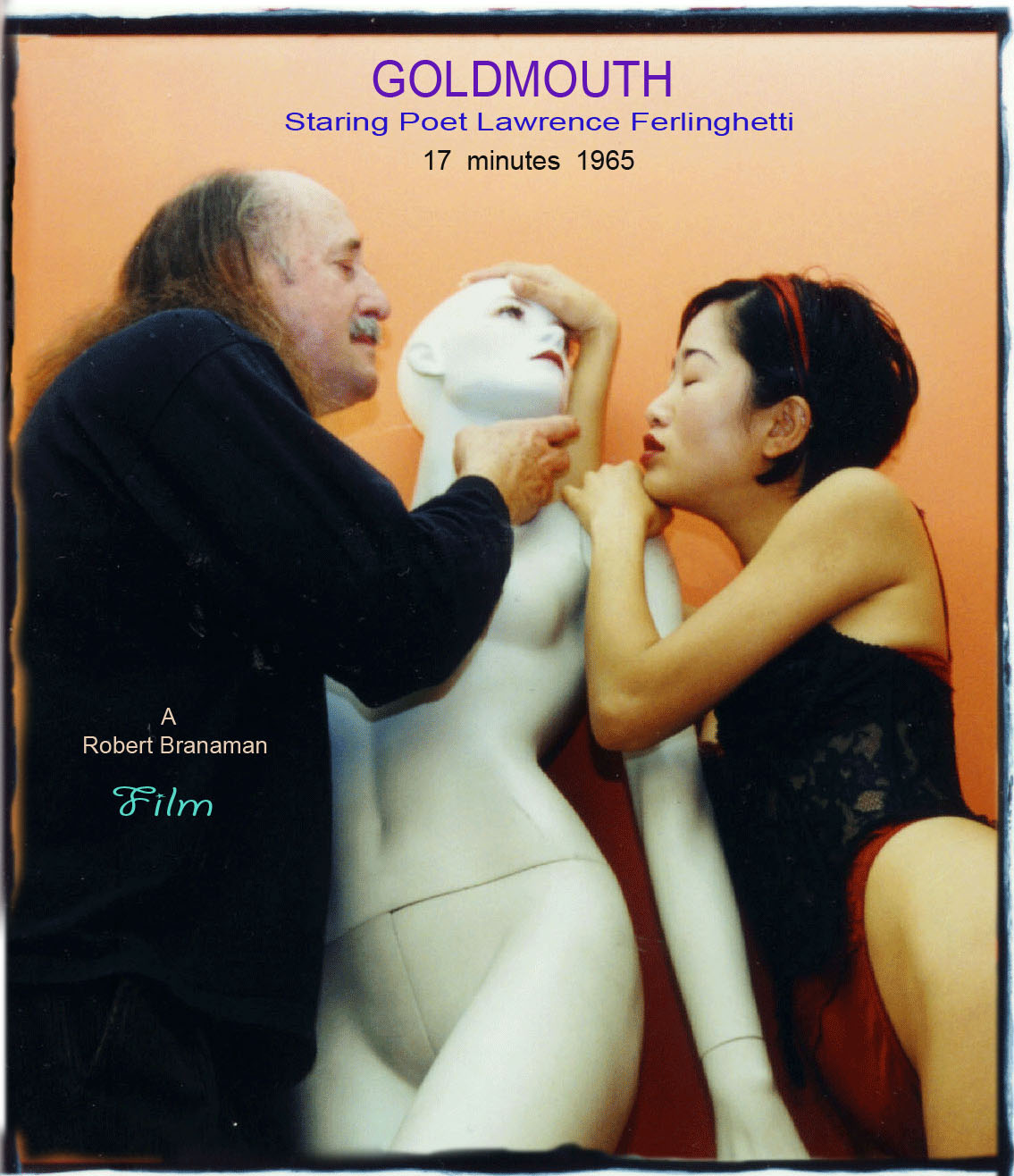

In a June 28, 2013 show of Robert Branaman’s films at Beyond Baroque (the St. Mark’s Place of Venice Beach, California), where Branaman is the visual-artist-in-residence, the line-up was as follows: Goldmouth, Burn, Karma, Burn, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, and Bygone Daz: From older films (60s & 70s). These were presented as projected DVDs. In a phone conversation with Branaman, who now lives in Santa Monica, I asked how much of this represented his body of film work. “Of the primo stuff? 20%. Of the total, about 100th.”

In short, a filmography of Branaman’s work has yet to be accurately assembled, and some of his work that is still referenced, such as Ginsberg, has been lost. The original films are in 16mm and Super 8. One of his untitled Super-8 films was partially screened at PFA March 2, 2011 in conjunction with their “Radical Light” series.

The beginning of a documentary-in-progress, Who the Hell is Robert Ronnie Branaman?, by Guy Borges and Patrick Rosenkranz, is on YouTube. It is a fitting title. Known well by his contemporaries, Branaman’s own wild trajectory from alcoholism and addiction, to recovery fused with a near-cursed lack of self-promotional skills shoved him under the radar. (His good friend, Charles Plymell, suffers a similarly shocking lack of recognition, if for no other reason than his refusal to be his own publicist, even with an astounding novel like Last of the Moccasins.)

Allen Ginsberg wrote his Vietnam poem-critique “Wichita Vortex Sutra” in 1966, a collage of conversation and radio snippets from a portable tape recorder Bob Dylan gave him. Less known is that the term “Wichita Vortex” was a phrase Ginsberg heard from his friends Michael McClure, Bruce Conner, Charles Plymell and Robert Branaman, all who migrated to East and/or West Coasts from this strange Kansas center of America. For the most part, these figures also experimented outside of both the poetic and artistic disciplines they were often pigeon-holed in. Film, collage, stage plays, and photography exploded through the shifting paradigm of the 1950s/’60s Beat phenomenon.

In the late 1940s, Lee Streiff, a high school pal of Michael McClure and poet-printer David Haselwood, first transmitted this Vortex to the Beats. (Filmmaker Bruce Conner joined the Wichita High School East group in 12th grade.)

Streiff repeated a “Martian history” of some of Wichita’s “secret alien inhabitants,” which unsurprisingly included Streiff, his older brother and his friends, including a “vortex” that apparently pulled spacecraft to shipwrecked disaster. This idea was passed to McClure and McClure passed it to best friend Bruce Conner. They brought the mythos with them when they left Wichita behind, and in 1966, the Vortex was further hammered home in Wichita when Moody Connell’s Skidrow Beanery briefly became the Magic Theatre-Vortex Art Gallery. Branaman’s pal, writer Charles Plymell claimed he could actually feel the Vortex there! Weirdly, it even crops up in Native American legends of the area.

In 1987, Conner himself presented perhaps the first major documents of the movement’s history in a letter to Robert Melton at the Special Collections department of the University of Kansas library. Conner gets it mostly right, except he didn’t know the Exile of the Martians origin began much earlier than 1951 (1937, in fact—in a newsletter of Wichita’s high school sci-fi geeks), ending his letter with: “As Dorothy said—That’s the Vortex in Toto.”

As for Branaman…

I came to SF in the Spring and then again in the Summer of 1959…Charley [Plymell] came a few years later. Charley went to New York long before me…

Branaman’s numerous contributions and collaborations with William Burroughs, McClure, and Ginsberg now seem to be finally getting the cultural and historical place they deserve, helping to examine the larger multi-media aspect of the Wichita Vortex in its filtering of the American mind—deconstructing and reassembling its artifacts in ways that are now part of mainstream media culture. Ginsberg’s poem “Wichita Vortex Sutra” also can be seen as an extension of this same approach.

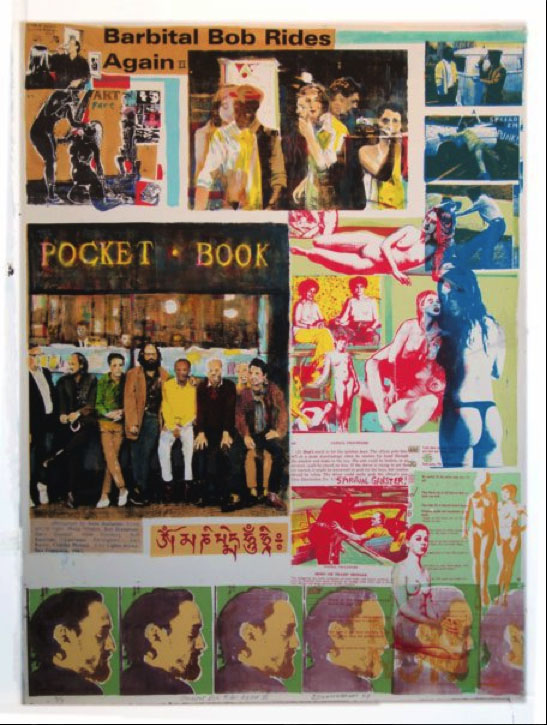

Enter Branaman’s garage in Santa Monica, California for some of these artifacts. Here is the continuing nova of Robert Branaman’s serigraphed text, paintings, and assemblages. He is still very active in his late 70s, this man Allen Ginsberg called “one of the most exquisite visionary artists in America.” Branaman’s running out of room. His assemblages are stacked like hubcaps. His paintings are piled together. His serigraphs lie on a work table—you might get one free if he feels like it. Branaman’s energy is exceptionally cheerful. He practices the Chinese energy work Qi Gong and is a longtime practitioner of Arica (Oscar Ichazo’s mystery school—see John Lily’s Center of the Cyclone for a good account) as well as a follower of Garchen Rinpoche, a Tibetan Buddhist master of high regard.

Branaman’s stories begin and they are uniformly hilarious. He virtually knew all the Beats—except he only once saw Jack Kerouac, drunk, surrounded in a bar, and Branaman thought Jack wanted to be left alone. Other than that, he can tell you stories about anyone you bring up.

PFA in the Radical Light book mentioned that they restored Goldmouth without contacting Branaman, believing him dead. These days Branaman does get mail addressed to the Estate of Robert Branaman. Ironic for a man in way better shape than most of his Beat peers that are left standing, more so considering he’s lived a life far more self-immolating; now 30 years clean and sober.

According to An Introduction to the American Underground Film by Sheldon Renan (Dutton 1967), Branaman’s film work started in 1958 with 8mm color rolls before he left Wichita. He continued in San Francisco with Super-8 movies like the untitled print that PFA partially screened (most of his Super-8 work is untitled…good luck, filmographers!). After some projects made with Bruce Conner, he then considered 16mm and larger concepts.

Since the scope of this article can really only serve as an introduction to Branaman’s work, I think it would be best to examine the film PFA chose to restore, 1965’s Goldmouth, which Branaman agrees is seminal and focal to his film work. To further complicate a potential filmography, the DVD currently screened is 5 minutes longer than the original, because Branaman has tinkered with a converted VHS-to-digital version, and the VHS was made by somebody shooting a video off the movie screen. So the version of Goldmouth I’ve seen has a pulsing TV flicker, which frankly, has its own aesthetic success. Branaman repeats some sequences and slows them down in the digital version. The plot, in the sense that Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon has a plot, follows poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti gaining, losing, and gaining once again a gold face-mask. Sometimes the mask is lost to a naked woman who makes love to it. The word “Goldmouth” suggests a slick talker and a great cunnilingist. It also suggests the energy of what a “Goldmouth” might be, and how it exists independently of the person who may possess it, as in the conventional sense of falling in love with one’s own mental idea of how a targeted person can fulfill one’s yearning. But that idea exists independently until one actually has a relationship.

“Goldmouth” is that magnetizing principle that can come to us and leave for no reason we understand. Such sexual dynamics run throughout virtually all of Branaman’s work in whatever format he chooses to express himself, coming to rest in his more recent Tantric Buddhist images of ritualized sexual intercourse, or yabyum. The pun on the sexed-up James Bond film Goldfinger is all the more likely when one realizes the Bond film was released only a year before this film was shot and edited. Some sort of crude optical printing seemed to have been created by masking certain areas, with window-like superimpositions. Branaman told me he hole-punched the film and glued bits of other film to those holes. What was once both color and black-and-white stock takes on blue and sepia tones in Bob’s digital version, with occasional splashes of faded Kodachrome, and further techniques of painting and scratching on the film, as well as using ends of film with their markings to “repeat” some of the painting and scratches.

Branaman is primarily an artist, so he uses film in a painterly way. His serigraphs frequently use superimposition, panels within panels, and repetitions of image to the point of photocopy-like degeneration. HIs film work, particularly realized in Goldmouth, restates this.

Robert Branaman continues to make films. He wants very much to make a Jean-Luc Godard-style feature.

May we get to see it, along at least with that other previous “primo 20%” of his film work.

Editor’s Note: A studio visit and interview with Bob Branaman, including exquisite images of his art and studio, can be explored at In the Make: Studio Visits with West Coast Artists.

Dear Mr. Branaman,

Did you visit Santa Cruz, CA mid 1963 thru 1965 and if so, did you get to visit; the “Hip Pocket Bookstore”? or in 1968 (ish) the “Barn in Scotts Valley (near Santa Cruz). If yes to either one:

My name is Melyssa Demma (dtr of Peter Demma co’owner Hip Pocket) I am doing collectives of material for book writing of my life as as the daughter of one of the “beatnick or beat” era.

I’m 53 and it’s about time, dont ya think?

Thanks for your time given you received this note to you…