Longtime OTHERZINE contributor David Cox will also be performing his latter-day operetta, Soviet Moon Fails about the doomed USSR lunar-landing on November 8th at Other Cinema!

Notes on Harun Farocki’s Bilder der Welt und Inschrift des Krieges (Images of the World and the Inscription of War), 1989.

“One must be as wary of images as of words. Images and words are woven into discourses, networks of meanings. My path is to go in search of a buried meaning, to clear the debris that clog the images.”

-Harun Farocki

Harun Farocki died this year. The world has lost a great film maker.

The Farocki film that had the greatest impact upon me was Images of the World, Inscriptions of War, made in 1989.

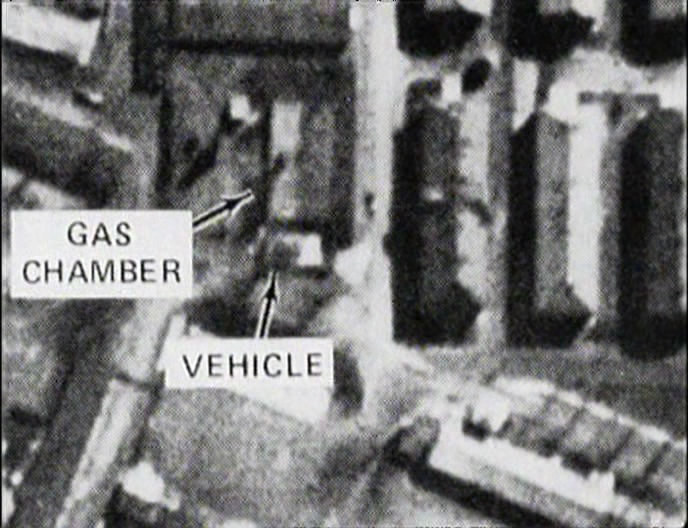

Taking WWII aerial photography as its central focus Images of the World, Inscriptions of War parallels the ideas in Paul Virilio’s book War and Cinema. In order to record the destructive power of their payloads, allied bombers were required to take photos of their targets. One such photo, taken on bombing approach of the Farben chemical plant (producer of poison gas Zyklon B used in the death camps) during a bombing raid, also unintentionally includes the nearby Auschwitz concentration camp. Decades after the event, the photo is finally analyzed in terms of being evidence of the actual camp, rather than evidence of the Farben target that was the photo’s initial purpose. Farocki’s narrator explains that the mid 1970s era CIA image analyst specialists who take on the job of labeling the newly identified aerial photo camp (not the original intended subject of the bombardier’s photo) are inspired by the then recent television show “Holocaust”. This titanic gap in history reveals the tragic and almost cosmic truth: the truth is hardest to grasp when the evidence is right before your eyes. Those image specialists in England, given the job of analyzing the photo during the war, were not given orders to look for a death camp, so never found, or even looked for one…

War and photography, Farocki argues, are linked by the need to classify and measure, but the way that an image is interpreted has everything to do with the context in which the image is placed at the time of interpretation. Just as John Berger’s “Ways of Seeing” drew attention to the importance of context for images such as landscape painting in relation to say advertising, Images of the World and the Inscription of War ‘draws bede’ on the ways in which official image production works both at the time it is done and as it changes over time to reflect new conditions.

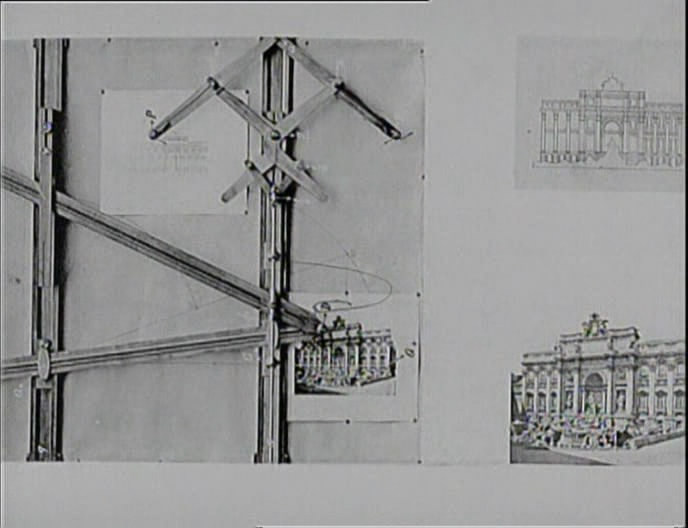

Farocki takes us back to the Renaissance to view the origins of the photographic mindset. He demonstrates Piero De La Francesca’s ability to mathematically ‘rotate’ and position the heads of his painted subjects the same way that contemporary 3D modelling programs do. He also looks at Albrecht Durer, whose seventeenth century illustrated books on perspective demonstrate how to draw subjects as if physical lines were converging on the eye through a hole in a fixed surface. This is arguably begins the idea of man-at-the-center-of-everything. Photography later only reinforced this privileged view, and implicit in this, Farocki would suggest, is the organizing logic of war.

There are, for instance, the 1960 pictures of traditionally clad Algerian women taken by a conscript in the then occupying French army, who has them remove their veils, something normally only done for the closest of family members in the most intimate of settings. The colonizer, the narrator says, must identify the colonized for the official records. A coffee table book is later published of the faces of these unveiled women. The controlling gaze of the occupation force uses photography to bend reality to its version of the world and how it should appear. It would not be too hard to imagine such a book emerging out of occupied regions of the Middle East today (are there any that are not?) published by a London or New York publishing house for middle class coffee tables.

Farocki shows us a photo taken by a German SS guard. It is an offhand snapshot image of a beautiful young Jewish woman as she walks, looking back over her left shoulder at the photographer at the Auschwitz death camp. Farocki’s narrator explains that the woman, for a brief moment in this act of gazing back, places herself briefly in the world of boulevards and busy city streets, as if the glance had come from the reflected gaze of say, a man in a window. Her captured gaze, perhaps an act sudden defiance in a setting that has been constructed deliberately to erase all such nuanced subtle individual identity.

Images of the World and the Inscription of War works with several dimensions at once, specifically through its examination of the multiple meanings of “Enlightenment”. A German meaning can suggest a police term to ‘throw light on the case”, or ‘clear up the case’. Airplanes during WWII would deploy lightening bombs to light up the ground below for photography. Cameras and guns and bombs were installed together on aircraft. Seeing preserved, bombs destroyed. Both actions occurred simultaneously at almost every scale on both sides.

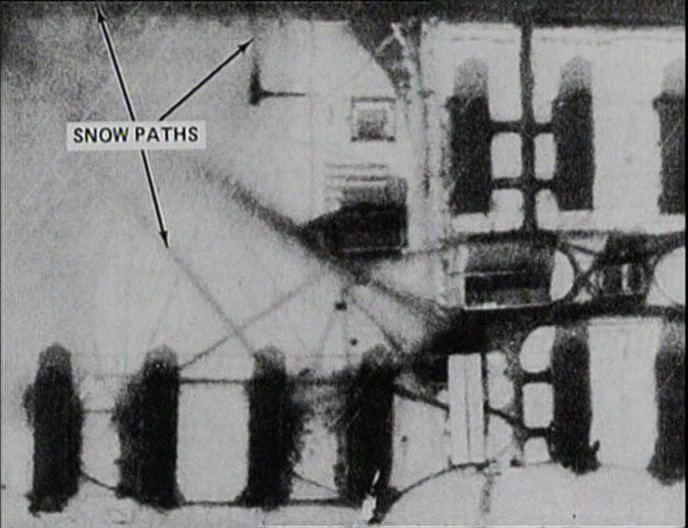

Camouflage tricks that the film reveals were used during war to disguise buildings, even whole city blocks. Real airstrips were made to look faded, fake ones were painted brightly to act as decoy targets. Whole stretches of land during war were disguised to protect factories and munitions works that lay beneath them. Factory roofs and sides were repainted to resemble apartment structures. Rivers and train tracks, (aides to enemy pilots), were covered with wood to mask them as obvious navigation points. Farocki juxtaposes this kind of architectural cosmetic treatment with a woman’s face being aggressively prepared by a make-up artist.

Farocki shows us police identikit systems in use in the mid-1980s (apart from everything else the film is a record of 1980s flight simulator technology, a kind of unwitting media archeological work to that end) that make use of photograph transparencies that scale up and down, upper head, middle nose and lower chin areas all separated out, the edges blurred. We view faces being made for us from infinite combinations. How radically such methods of human classification have ‘advanced’ since. After 9/11 and the concomitant Patriot act, the impulse to do so is as primitive as ever. Both the prison guard and police officer possess the base need to classify, organize and reduce the human subject to parts that can enter the database. It was as managerial then as now. Ghosts in the machine might today step in to recognize a gait or build a personality from metadata now, but such algorithms of the new aesthetic are not so much computers wanting to pass the Turing test to prove human, as to better fuse the banal world of database with non-database. Every manger and cop’s desire, perhaps?

Some memorable moments from the film:

- A Lufthansa flight simulator seen from outside as the massive cockpit is lifted and lowered by hydraulic ‘legs’ simulating the effect of pitch and yaw, jet sounds blaring.

- A fine art life drawing class is drawing a female nude model. The instructor explains. “You cannot draw and think at the same time”

- Close ups of the unintended allied aerial photo of Auschwitz. The female narrator lists the parts of the camp, joining the parts with the word ‘and’..

- A story about the failure of metal press shop whose artisanal methods of making steel cylinders finally ended in the 1980s with a lack of demand. The methods of spinning metal having remained the same since the earliest days of bell making. The parts left outside to rust. At the height of the war the firm had made the housings for searchlights to light up the bombers, which in turn dropped ‘flash’ bombs, to illuminate the ground for the cameras.

- Images of a wave-making test laboratory with the waves creating artificial surf. Presumably to test model boats.

- Identikit technology circa 1989. Strangely beautiful combination faces being made at random from various photos of strangers upper heads, middle nose and lower chin areas, each independently scalable. Reminds me of the microfiche machines pre-internet in libraries in the 1980s to view newspaper archives.

- Camouflaged aerial features of wartime landmarks, including dummy housing, dummy trees, dummy factories even, painted on top of actual structures.

- The whole theme of seeing, deception, decoys, makeup, perception, interpretation, how all this was so much in the center of cultural life in the mid-to-late 1980s and how postmodern thinking and art was expressed through the fracturing of images, sounds. Popular versions were hip-hop and cut-up culture.

- Early computer-generated battle simulations and flight simulators aimed at military contractors.

- Shots of enormous 1980s clunky-looking helicopter head-mounted display units worn by a pilot with a handlebar moustache, the footage accompanied by cheesy tradeshow voice-over, “Here we see that the pilot must clear the bridge.”

Images of the World and the Inscription of War explores the way that image analysis and image production are themselves part of a global worldview whose impulse is inherently one of control, management, organization along determinist, linear terms. Photography and manufacturing as well as concepts of labor – the reduction of people to pure components for use and replacement or destruction underpin modernity. Images join the other instruments that have framed the rise and fall of cities and civilizations. The digital acceleration of technology the world has seen since the film was made has only intensified the main points the film addresses.

The dialectical editing approach intercuts concepts such as camouflage with ‘makeup’. There is a relentless quality to the film as well. The process of analyzing images becomes the mindset that you as the audience member find yourself interpreting as well and in this way the film is strangely recursive. Like the main character in Antonioni’s “Blow Up”, we end up scrutinizing Images of the World and the Inscription of War for details that may or may not be there, just as the subjects of the film do, in their quest for details. The difference is the onscreen photo analysts who examine aerial reconnaissance photos for hidden tanks do so with the mindset of managerial specialists, and Farocki is inviting us to view his film through a kind of postmodern filter of self-reflexive uncanny doubt. By watching the film we cannot really take any image for granted any more. It is all a construction.

Goodbye Harun Farocki.

Rest in Peace.

Bilder der Welt und Inschrift des Krieges,

Images of the World and the Inscription of War

Director, Scriptwriter: Harun Farocki

Assistant Director, Researcher: Michael Trabitzsch

Cinematographer: Ingo Kratisch

Animation Camera: Irina Hoppe

Editor: Rosa Mercedes

Negative Cut: Elke Granke

Sound: Klaus Klingler mixing: Gerhard Jensen-Nelson

Narrator: Ulrike Grote

Production : Harun Farocki

Film production: Berlin-West, with financial

support from kulturellen Filmf�rderung

NRW producer: Harun Farocki

length: 75 min. format: 16mm, col., b/w,

1:1,37 first screening: 10.11.1988,

Duisburg (Duisburger Filmwoche)

1 comment for “Images of the World: Notes on Harun Farocki”