In the following article, Huckleberry Lain questions the impacts of gentrification on cinema and the exhibition space. Leslie Dreyer will likewise confront gentrification through the elucidation and exhibition of documented resistances to this same process within our local community at Other Cinema’s Contested San Francisco screening and talk on April 26th, 2014!

For me, cinema died today. Not with any conversion or transition of our beloved images, but with the erasure of my first movie palace. The Park Theatre, in Menlo Park, California, was 66 years old when the property owner decided it should be flattened and turned into office buildings. That might not seem very old, but for California architecture, it is considerable given the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906.

The Park Theatre, just before its demolition.

Progress is haunting. Technology ostensibly advances to make things easier, cheaper, and more accessible, but leaves its impression as the absence of the socially valuable at the expense of bolstering the economically secure. To what extent and in what ways will we allow this insatiable progress to determine our lives? This question spun around my head eleven years ago when the Park first closed its doors as a cinema to the public. The specters of this question haunt me today.

Situations like this really make me wonder if the invisible decisions made in this moment of late capitalism are really in line with our values. When the pursuit of profit goes before culture, history and community, it seems that it loses purpose. The recirculation and amplification of capital has affected architecture rather differently than other arts; though, each form has of course in its own way seen the effects of commercial and corporate interest. With property, but more specifically, architecture, it is the owner that decides its fate, which certainly affects our lives directly not only as patrons, but as lovers of a space, as people who may very well have a shared history with a space (and often, even a greater share of this history than the owner themselves in urban areas). But at what point is a public sufficiently and rightly empowered to decide that a building is historically significant, preventing an owner from doing what s/he will? A building, like a painting, can be protected, but this involves an active city council, architectural experts, and an interested community. To what extent do these communities and institutions speak for the ownership imparted to the public through a collective remembering of that building? Property, a demarcation within abstracted geographical coordinates and likewise within a newly deterritorialized market, has unfortunately ironically surpassed the oft more historically significant architectures upon the property itself as a wellspring of capital. Finally, at what point does it become irresponsible to purchase something with no more personal investment than the money it could potentially generate? And at what point did such a decision become a cultural common sense?

The Dorothy Chandler Pavillion is only 50 years old, and yet, the Los Angeles Conservancy selected it as part of their Last Remaining Seats film series in honor of its historic significance. Menlo Park is its senior by sixteen years, and it left without a whisper. Eleven years ago, owner Howard Crittenden closed its doors; the protests against the closure, made by a few local residents and Landmark Theatres, were ignored. I had previously left for college to New York and later Los Angeles. Upon my return to the Bay Area, Mr. Crittenden decided to destroy the Park.

Previously, humankind’s constructions were made to outlive their makers as a way of demonstrating the cultural power and creation of that period. Now real estate developers are driven by profit, which is driven by current market trends. The very capital produced by the new ownership of property (space demarcated within a more general location) and the building on it immediately, burdens its owner with the responsibility to regain the capital invested in it. In a culture of greater and faster consumption of fads, landmarks, these places in which public historical significance is created, barely have a chance to find their true personalities before they are razed and forgotten. As James Brook carefully noted, “In a critique of the lamentable state of American cities, there can be no appeal to the nostalgia for lost traditions and ways of life; our appeal can be only to the future. This should not necessarily excite optimism.” (“Remarks on the Poetic Transformation of San Francisco”)

In this same essay on the development and short history of US cities, Brook describes a man named Nicholas Calas, a European writer who immigrated to New York City in the 1940’s. Having come from the old world, he couldn’t stop writing about the bizarre architectural hodgepodge that was the Big Apple, with an endlessly eclectic history grafted upon and within every building he saw. Calas believed that the poetry of a city could be found in the forgotten spaces and “flow” from one wondering place to the next. In this way, buildings and places develop their true character only after their initial purpose has waned. This is what I saw in the Park Theatre. After 50 years of movie goers, employees, accidents, violence and love. It was in the walls.

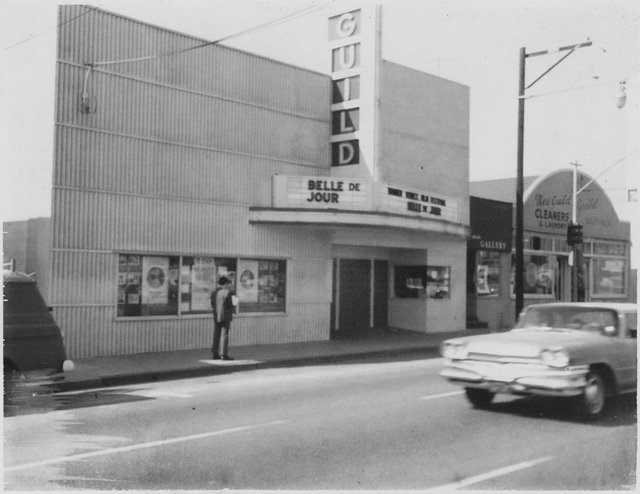

In an age where most people are regretting the slow fade out of the medium of celluloid film, for me, this overrated argument takes a back seat to my objections to the erasure of the elegant and classic movie palaces, which are now on the verge of extinction. Knowing that Mr. Crittenden is also the owner of the last remaining classic cinema palace in Menlo Park, the Guild (due to turn 90 in just about two years from now), will we be lamenting the destruction of that elegant construction in ten years time?

I have a 1899 postcard of the market square in my hometown.

In it, I can show you my grandparents’ house where I lived as a child, the church where I was baptized, where my grandfather and great grandfather were buried, I can show you the building where my favorite cafe was, the bookstore, the pharmacy, the cosmetics store and the bank. Well over 100 years old, this postcard has the ability to make me homesick because I recognize every building and have a story associated with it.

There are, of course, some things that are not on the postcard, like the busy street with hybrid cars, the fountains on the square and the artistic wicker fences overgrown with roses. Those are new developments, especially all the roses. It’s not that I want things to stay the same. There are modern businesses there now, people lead busy lives. My family is associated with a number of cities in Europe, but in most of them, unless they were demolished by war, I can tell you the same story. My family and my identity, for generations, has been “in these bricks” and I know I am home.

I live in San Jose now, and I recently took the history walk tour and sadly noticed that most of it is on plaques that say “here stood” and “original sight of”. There are Victorian houses here that would give San Francisco a run for it’s money, but a lot of them are falling apart, rotting, forgotten and soon they too, will be no more. The past is gone, this is a momentary city that I won’t be able to show my kids. I am not part of the change here. I am not tech savvy, I have gotten older and more nostalgic and the changing, greedy landscape is just one of the reminders that I don’t belong here. That’s why I am going back next year to a place that I know I can make a difference in.

But my difference won’t be in a new, temporary building, that will be gone with nothing to show for it in less than a generation. I want my change to be dusting off old walls and imprinting myself onto the layers of history that have been before me, so that my grandchildren can also look at these old postcards and think of me as well. I want to stand on my feet in a place where I don’t feel the ground slipping from underneath me because of someone else’s drive to make money. I’m sorry, California, the ground here is too unsteady to grow roots. And it’s not because of the earthquakes.

And please – please look at this website. It’s the Box of Ghosts project by the Buena Vista Neighborhood Association. http://www.bvnasj.org/SanJoseThenNow2.htm