Nik Nerburn (born 1989, Bemidji, MN) is a research-based storyteller, experimental historian, filmmaker and archivist. He’s interested in essayistic interventions in archival materials to explore regional histories, focusing on stories that stand at the intersection of power, memory, nostalgia, and place. He’s now based in Atlanta, GA. His film, In The Shadow of Paul Bunyan, will be premiering at Other Cinema’s No-Thanks-Giving show on November 29th!

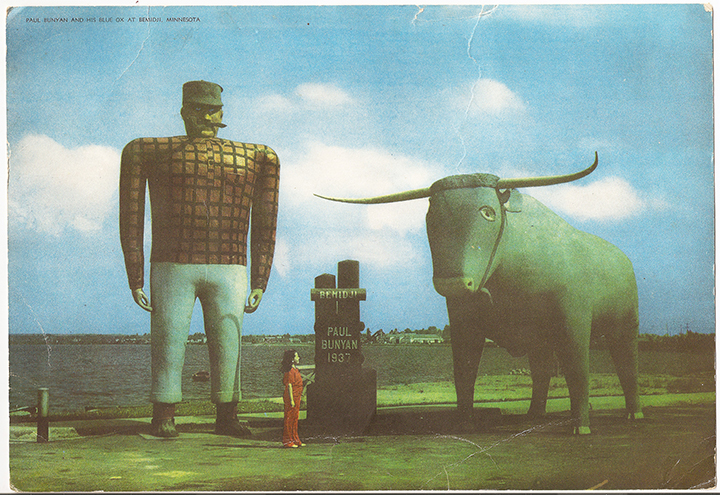

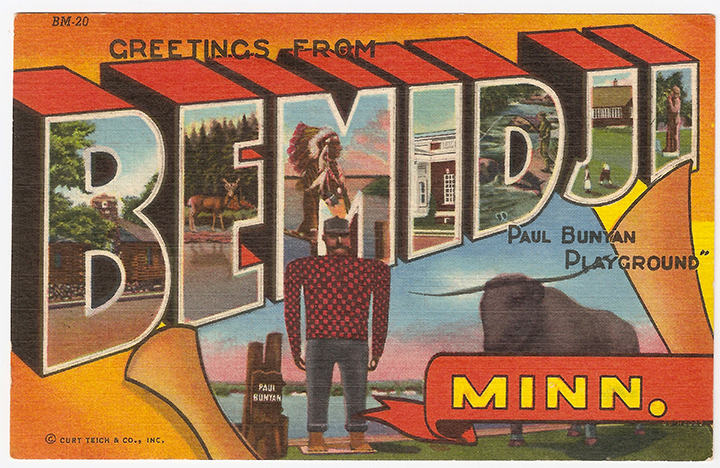

These artifacts are a few of the materials I’ve been collecting in my ongoing expanded multimedia explorations of the myth of Paul Bunyan. Paul Bunyan is commonly understood to be a folk character of the upper midwestern United States, where folks have devoted a considerable amount of our characteristic industrious energy to him and his image. Any traveler of Michigan, Wisconsin or Minnesota knows at least a few of the hulking idols that dot the highways and constellations of our small, struggling towns. He appears as statues, paintings, memorabilia, and a theme park, all of them possessing a rough-hewn folk quality that is at times equally charming and frighteningly uncanny.

I’ve been devoted to mercilessly running the story of Paul and Babe through my own interpretive sieve, fertilizing the folk symbols until they finally reveal an impression of the vernacular (and frigid) landscapes of my youth! The results are ongoing – check in at http://www.intheshadowofpaulbunyan.tumblr.com for more.

“Have you ever been to Bemidji, Minnesota? Well, lemme tell you about it, since I grew up here. If the whole city was ever buried under some radioactive ash, forever preserving one mundane moment of this sleepy settlement in the fossil record, that whoever’s lucky enough to dig us out, a million and one years from now, will most likely conclude that we worshipped Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox as gods.

Don’t believe me? Take a look around! Once you start to pay attention, you’ll see them everywhere.

On my first day in kindergarten, my first assignment was to draw a picture of Paul and Babe. And then, after that, a man dressed up as Paul Bunyan came in and told us all Ole and Lena jokes in the gym. You think I’m lying?”

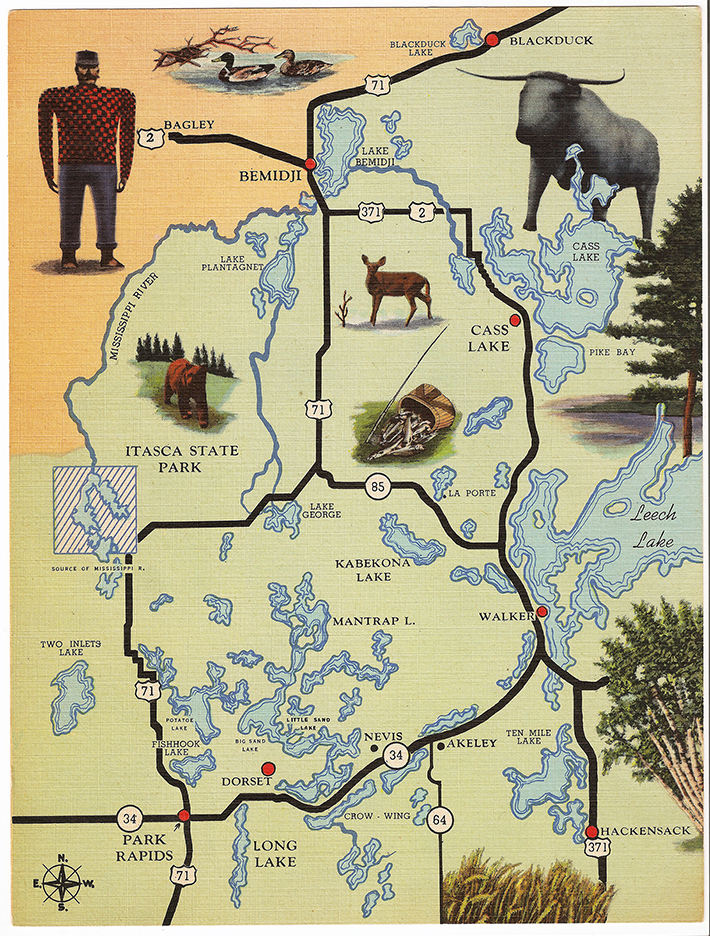

“Then, they told me that the reason Minnesota had so many lakes was because they’re all Paul Bunyan’s footprints. I remember looking at a map, not really believing that it was true, but I was a little shocked when I saw how much Lake Bemidji did kind of look like a footprint.

Yup, one day when you come visit, you’ll see what I mean.”

“Maybe you don’t know about Paul and Babe? Well, that’s fine. Not everyone does. But the story goes back a long ways, ya know. I guess you could say it started back in the olden days, when this place ya’ll call Minnesota was overflowing with French, Sioux, Winnebago and Ojibwe trappers. Back to the 1700s, when this place was a heck of a party! You know, some people say that Paul was French – but lemme tell you that that just ain’t the case! Cause you see, the loggers didn’t come til later – til this whole place had been carved and mapped by some pampered little Eastern hands, given a name and an outline on a map and settled with white people faster than Garrison Keiler can say Lake Woebegon. Oofdah!”

“Now, in Minnesota, we like things big. One day, when you come to visit, I’ll take ya around and show ya!”

The challenges presented to the filmmaker wishing to paint a portrait of pioneer Bemidji are varied, owing primarily to the fact that much of the visual record of Bemidji’s early years were lost to the trash heap. The 5×7 plate glass negatives from itinerant photographer Niels Hakkerup’s studio were left to rot in the alley behind his studio. Local historian Charles Vandersluis, who remembers handling the plate glass negatives in the alley with Hakkerup’s son, Bjorn, believes that they were tragically lost to the dump. Since the trash pile never reveals its secrets, we have little genuine documentary evidence of those formative frontier days. As such, I’ve chosen to use repurposed educational, industrial and popular films (along with some authentic archival oddities) to contextualize our regional obsession with the plaid patriarch, finding inspiration in the tradition of the great film collagists. Now, don’t worry – we’re still committed to documentary truth, verifiability and accountability. But collage, as an investigative documentary mode, turns out to be peculiarly well- suited for deconstructions of popular culture, regional myths and the history of representations.

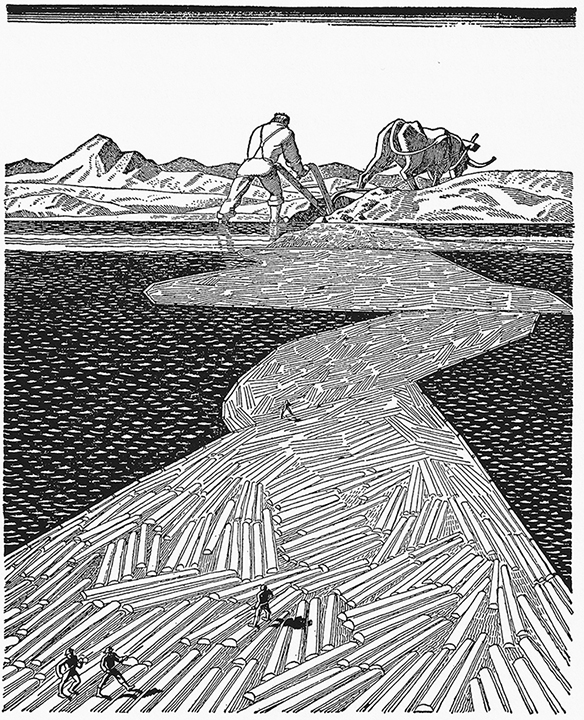

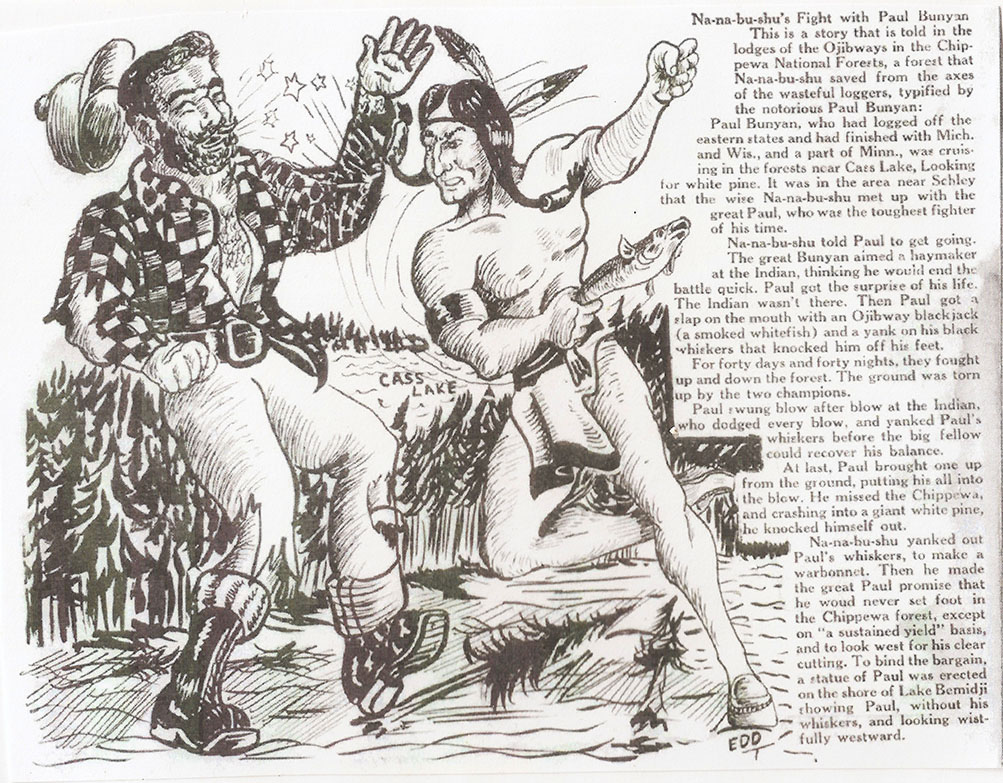

For one, certain historic patterns of problematic representations reveal themselves – native americans consistently being invoked through tiny bodies, ala Indian in the Cupboard or Disney’s horrifically racist Little Hiawatha cartoon. Collage makes it easy to illuminate this pattern, rather than spelling it out in media analytic terms. Secondly, the wildly fun dislocation that collage creates makes grappling with issues at the intersections of of race, class and gender much more palatable for your audience (not that palatability is our main concern). Finally, out of collage emerges a poetic veracity, vibrant in its lies and somber in its truths, that speaks directly to the audience who’s been raised on a heaping diet of tall tales. Like Paul’s mountain of flapjacks, there emerges a poetic truth from the mists of montage, one that speaks more accurately to the region than any image a sober recollection of facts and figures could forge!

My own analysis of Paul activates the race, class and gender faultlines of the myth. In the stories passed down of Paul’s greatness, where do we see the history of native displacement ? Why does’t Paul ever tell use the story of the 1917 lumberjack strike, when lumberjacks across northern Minnesota shut down one of the largest lumber plants in the country? What role does Paul play in the construction of a colonial white masculinity, a tradition brought to Minnesota so long ago by the English colonists (who went to absurd lengths to impose a racial hierarchy on everyone the encountered, with themselves at the top, and the Ojibwe, Sioux and French underneath)?

Secret histories tend to be secret for a reason, and these counter-stories still remain in the shadow of the biggest story Minnesota tells about itself – the story of Paul Bunyan. He’s one- dimensional, and we like him that way. In our tradition of denying the complexity of the Minnesotan Paul Bunyan, we also carry on the tradition of denying a complexity within ourselves. And just because it’s a tradition doesn’t mean we should keep on doing it.

-Nik Nerburn, Atlanta, GA, 2014

I. A Folk-vertisement for the Ages

Like any good story, Paul Bunyan himself has his own creation myth. The Paul Bunyan story originated, folklorists think, in the upper great lakes region of the United States. He may have been based on a real person, but most likely he was a simple story told by seasoned loggers to tease and embarrass greenhorns. One school of thought holds that Paul may have his origins in the French Canadian War – Bon Jean being the French name of a large, skilled fighter, which we now know as Bunyan. The documentation, what little there is, is unclear.

What we can say is the modern origin of the Paul Bunyan myth began in 1922, when an aptly named William Laughead (pronounced log-head!) used Paul Bunyan as a mascot for his cousins’ new logging mill in Westwood, California. The Red River logging company had its humble beginnings in Akeley, Minnesota, which is now the home of a truly frightening Paul Bunyan statue and museum dedicated to him. Laughead had lived and worked in the lumbercamps of northern Minnesota, perhaps even near or in Bemidji, during the so-called ‘golden age’ of Minnesota logging from 1900 to 1908. He worked in various positions, which gave him an intimate knowledge of the slang and stories bandied around the camps – so the story goes. He collected various Paul Bunyan stories he knew into an advertising pamphlet called “The Marvelous Exploits of Paul Bunyan As Told In The Camps of the White Pine Lumberman For Generations During Which Time The Loggers Have Pioneered The Way Through The North Woods From Maine To California; Collected from Various Sources and Embellished for Publication” (as you can tell, he didn’t have an editor). In 1922, after three miserably puny publications (not unlike the one you’re now reading! Ha!), Laughead’s character took off beyond his wildest ambitions.

People from all over the United States were ordering copies of the pamphlet– not to shop for lumber, but to read the comics and look at the pictures! People were hysterical about Paul. Max Garenberg, writing in 1950 in The Journal of American Folklore, put it thusly:

Within a few months after its publication the entire edition of Io,ooo copies was exhausted, and a reprint of another 5,000 copies could not satisfy the requests of children, teachers, folklorists, statesmen, librarians, soldiers, and sailors-persons of all interests and walks of life-which inundated the company’s offices and are still perplexing its successors. Jimmy Roosevelt wrote Archie Walker what a kick his father got out of the book. A commissar of Soviet Russia was interested in the propaganda angle and wanted a copy for translation. Only recently a woman wrote the Paul Bunyan Lumber company, present owners of the Bunyan trade-mark, for a copy of the pamphlet, which she had received in Manchuria several years ago and was now worn out.”

Laughead is responsible for all the characters we know and associate with Paul – sidekicks with names like “Johny Inkslinger” and “Shot Gunderson”, “Chris Crosshaul” and “Sourdough Sam”. Laughead was also responsible for the invention of Paul’s most famous sidekick – Babe the Blue Ox, named so because Laughead recalled it was “such a funny name for such big animal”.

“Not a lot of people wonder about Paul. He’s kinda timeless, ya know? But Paul’s an immigrant, too. And it might be hard to hear, but he didn’t come with the lumberjacks. He came with the advertising men. Specifically, one man.”

II. The Ole and Lena Department of Landscape Studies

I was told the Paul Bunyan stories in school in a folksy tone, as if relayed by a grizzled lumberman across a campfire north of the continental divide. Paul stopped all the logjams by pulling the Mississippi river straight. He ate 10,000 flapjacks. His griddle was greased by little children with butter tied to their feet (in the original Laughead story, it was “greased by colored boys who skated over the surface with hams tied to their feet. They had to have colored boys to stand the heat”). He logged off North Dakota, stomping down all the stumps after he was done.

I always thought of those stories as being cut from the same cloth as Ole and Lena jokes – the product of too much time spent working in the woods during long winters, yarns spun in the distant haze of an historic hallucination. From when someone who had spent too long in the frozen, barren, godless primordial misery of a Minnesota January and needed a small, sly joke to keep the spirits up. He was a shared past – a gentle giant from a golden age. Without him, we might pause, drop our characteristic optimism for a moment and ask the most dangerous question of all – why did our ancestors punish us by choosing to settle here? If Paul and those loggers could handle the cold, then dammit, so can we.

This is where we’re from, those stories seemed to say. Paul and Babe emerged from a world every bit as alive, plastic and metaphoric as Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Macondo. Understood through those stories, the Minnesotan landscape seemed to take on the qualities of a northwoods magical

realism, complete with rearranging forests, winters of blue snow, rivers that loggers can pick up and snap like a whip while people vacation in footprint shaped lakes. We retell the stories of the loggers to stay connected to our frontier past.

Except, of course, that there’s one problem. None of it is true. Folklorists who’ve studied the subject have found that in repeated interviews with lumber workers, very few had recall hearing any Paul Bunyan tales while working in the woods. For instance, in an interview with Roy and Gladys Snyder, who worked in logging camps between Grand Rapids and Bemidji in the 1930s and who married in 1937(the same year the infamous statue went up in Bemidji), neither of them had any recollection of any lumbermen telling any such tales. In nearly two dozen interviews with those who had a tie to northern Minnesota’s logging industry of the 1920’s or 30’s, one researcher found only one person who recalled hearing any Paul and Babe stories in the logging camps.

III. History as Leftovers

Mary Lethert Wingerd describes the Minnesota Centennial in 1958 in her book “North Country: The Making of Minnesota”.

“The themes of progress that the [centennial] pageantry celebrated and advertisers promoted could not help but make us proud of our North Star state, with its ten thousand lakes, progressive politics, renowned educational system, innovative businesses, unsullied natural resources, and enviable quality of life. All of this was true – but it was not the entire story. The heritage we honored that centennial year illuminated for the world a distinct regional identity that set us apart from other states and, at the same time, situated Minnesota in the larger American story. But heritage does not suffice as history. As scholar David Lowenthal points out, heritage is crafted to affirm what we wish to be true about ourselves, whereas history strives (albeit imperfectly) to discover the truth about the past. History, of course, is far more complex and problematic than heritage. History must come to terms with injustice and tragedy as well as achievement, asking hard questions that heritage, steeped in nostalgia, tends to ignore. None of this served the objectives of the centennial planners.”

Heritage is what we wish was true about ourselves. It’s the junk we sell in the gift shops, the historic plaques, the stories we tell to our kids, and of course, it’s the statues. History is really just a word for the leftovers. All the stuff that doesn’t fit in with the story we tell ourselves about where we came from.

It just makes me sad to think that sometimes the stories that don’t make the best statues are the most important ones to keep on telling.

IV. Here Lies Paul

Up north of Bemidji, if you know where to look, you can find Paul Bunyan’s grave.

It sits in a park off of the highway, next to a scruffy mural of Paul and Babe inside of a WPA era picnic shelter. The grave itself is an enormous lump with two white cedars standing at the foot. Between the cedars is a simple poem carved in stone.

Paul Bunyan Born 1794 Died 1899 Here lies Paul, And that’s all.

When I first read it, I was almost shocked at its characteristically Midwestern understated-ness.

Our pathetic attempt at mythologizing our history ends here, with a phony plaque at a roadside pull off. But yet, the hand-carved letters and the lovingly arranged stone masonry on which they rested on left me quivering with wistfulness. I can feel my memory of the hazy giant bubbling forth, equally hallucinated, recalled and dreamt in a spiraling panorama of unspoken desires and half-remembered tall tales. Can a memorial to a false giant really overwhelm me so, engulf me with such quaint melancholy? Here lies Paul, and that’s all.

“The real joke about Paul’s grave is that it’s not a real grave, of course. It’s a grassy lump made by a septic tank, which you see pretty often around here. I think it’s bad planning, because when any future archeologists try to dig it up and divine the source of our wonder and devotion to Paul Bunyan, they might be disappointed when they don’t find a body, but just a bunch of our poop.

Maybe it’ll add to the mystery. Or maybe by then, it’ll make perfect sense.”

1 comment for “In the Shadow of Paul Bunyan”