by Karl Mendonca

While the intermission has long been phased out from cinemas in most parts of the world, the “samosa break” (as it is referred to in Bombay vernacular), is very much a routine and ongoing experience for audiences in India. For those unfamiliar with the concept, the mechanics are quite simple—about halfway through a film (be it a Bollywood, Tollywood or even Hollywood release) at a cliffhanger or crucial plot point, the theater lights turn back on, interstitial advertising is displayed on the screen and the audience can stretch their legs and visit the concession stand. So, when veteran Bollywood actor Aamir Khan declared a “no-intermission” exhibition contract for his film Dhobi Ghat in 2011, the debate that followed was to be well expected. This was the first time in the history of popular Indian cinema that a filmmaker, or any entity for that matter, had tried to disrupt this entrenched practice. On one hand Khan’s request garnered praise from fellow filmmakers and cultural critics in India who supported his argument for an uninterrupted, “pure” filmic experience. On the other, cinema owners (especially of the newer multiplexes) responded with vocal resistance, complaining mostly about lost revenues from food sales at concession stands. Although the fracas settled quickly with cinema proprietors ceding to Khan, the event calls attention to a surprising oversight in South Asian cinema studies—apart from Lalitha Gopalan’s Cinema of Interruptions (2009), the intermission itself is an entirely under-theorized subject of critical inquiry.

But what would a study of the intermission entail? To return to the image of the concession stand in the theater, the challenge is not just to critically examine the vast body of interstitial advertising projected during the break, but also follow the action out of the cinema hall, i.e., to think of cinema as infrastructure. Again, while there is a significant body of work on Indian cinema that has focused on the textuality of film to engage with a varied range of themes such as national identity (Chakravarty, 1993), spectatorship (Vasudevan, 2011) and urban history (Mazumdar, 2007), there has been scarce theoretical attention paid to the material aspects of film production, specifically its infrastructural underpinnings. Already, I have begun to use “infrastructure” in a general sense to refer to logistical aspects of distribution. Given the centrality of the term, it is important to provide a better definition. From the OED, we learn that infrastructure is etymologically composed of two parts: “infra” is a Latin prefix that has a dual meaning of both “below, underneath, beneath” or “within,” and “struct-” that in classical Latin was the past participle stem of “struere,” or to build (Sack, 2015). To conceive of cinema as infrastructure then, demands that equal attention is given to both the modes of signification proposed by the advertising forms as well as the underlying material conditions of labor, production and distribution.

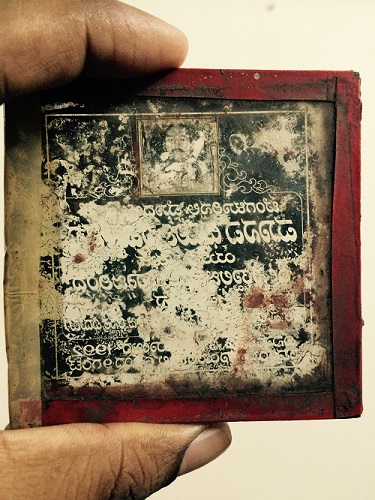

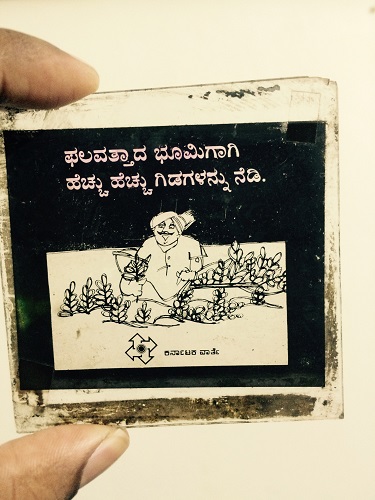

As working context for such an endeavor, this paper focuses on the Blaze Advertising network that held a monopoly on the distribution of cinema advertising across India from the 1960’s until the 1980’s. The network had its beginnings in Bombay in the 1950’s when journalist Mohan Bijlani and his busines partner Freni Variava founded Blaze, a print based magazine that covered news and events related to the popular Indian cinema industry. Building on the success of the magazine, the duo pioneered an innovation in Indian cinema advertising when they printed ads on the back of theater passes for the film Mughal-e-Azam (1960) at the Eros theater in Bombay. Blaze subsequently expanded on the types of cinema advertising to slides and films that were played during the intermission, establishing a monopoly on distribution across India in the process.

While Blaze Advertising provides a well-suited case study for the project outlined so far, their story takes an unexpected turn. In 1986, their monopoly was disrupted by the Government of India under the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act (1969). The 1980’s also saw a decline in the overall popularity of cinema in India, due in part to the aggressive growth of television programming and a boom in the number of households with television sets. Rather than continue to compete in cinema advertising, Blaze re-purposed their network as a domestic courier company (similar to FedEx) with a franchise based business model that exponentially increased their presence across India.

There is a final twist to the story of the Blaze network, that relates to the available (or lack of) archival materials and media forms. While there are a few privately held archives of the cinema advertising, the most substantial trace of the Blaze distribution network exists in the form of database logs that serve as the back end of the courier tracking website. An entire warehouse that stockpiled decades of advertising was recycled when the Blaze switched from cinema distribution to courier service. A bulk of the paper based records, including manifests, log books, exhibition certificates and receipts, used to track and manage both the cinema and courier distribution, were destroyed by heavy flooding that completely submerged a second company warehouse in 2005. It not without a sense of irony, that an electronic database will play a significant role in historicizing a part of cinema history in India that has left scant other artifacts.

My analysis is far from complete, but this is an opportune moment to pause and assess the critical ground gained from this rather peculiar case study. Firstly, even as the structural tradition in experimental cinema has long since made the labor of filmmaking visible and central to the work, the intermission alerts us to the hidden labor of infrastructure. The cinema screen serves as an interface (to use a new media term) or boundary object between the subjectivity of labor and the audience, both interpellated by the logic of distribution. Secondly, the remarkable transformation from cinema to courier distribution, takes us further away from the cinema hall, but puts the Blaze network (and Indian cinema!) at the center of ongoing discussions about the role of digital technology and governance in India. Over the last decade or so, initiatives such as the National Identity Card Plan and the Employment Guarantee Scheme are but a few examples of a range of ongoing initiatives where the implementation of electronic systems promise transparency, equitable distribution of government benefits, better governance and broader access to digital technologies towards the development and uplifting of minorities and disenfranchised groups. With its longitudinal lifespan, Blaze provides the ideal vantage point to understand how the logic of distribution operates within a longue durée of structural, political and economic transformation. And finally, by approaching both the network and region of South Asia, not as objects of study, but as sites of theoretical possibility the project is an opportunity to “provincialize cinema.” Put simply, how might the episteme of the area and Blaze Network change our understanding of cinema?

I was hanging out with Bob Basanich (sometime guitarist for Negativland and co-founder of the Olympia Film Ranch) when touring with my films in 1992. Bob was the among other things at the time, the 35mm projectionist at a Drive-In theater outside Olympia, Washington. During intermission he projected some excellent old 1950s “Intermission” and “Snack Time!” slides as well as others advertising long-defunct car dealerships and other local businesses that he’d found in the projection booth. He also screened a short film he’d made from the offcuts of 35mm he’d found lying around in the same booth.

All this in between the main show which was Alien 2 and Predator 2.

Shooting stars also appeared above the screen that night amidst the Douglas Firs…

DC