by Faith Arazi

I first came across Kathryn Ramey’s Experimental Filmmaking: Break the Machine (Focal Press, 2015) a couple months ago, when an old professor of mine forwarded me a pirated copy. Up until this point, my understanding of experimental film has been rather informal, as there is some required reading I have yet to get around to. My knowledge of experimental film has grown from sensational oral histories, volunteering at shows, mentors, borrowed books, and internet forums. I sense my involvement with experimental film has just begun, counting an arrival to Artists Television Access at just little over a year and half ago as the christening date. If there is any reason as to why I have been compelled to stick around, it’s not because of the money or the outcome, it’s because of the community. This idea is what remains central to Ramey’s text.

I first came across Kathryn Ramey’s Experimental Filmmaking: Break the Machine (Focal Press, 2015) a couple months ago, when an old professor of mine forwarded me a pirated copy. Up until this point, my understanding of experimental film has been rather informal, as there is some required reading I have yet to get around to. My knowledge of experimental film has grown from sensational oral histories, volunteering at shows, mentors, borrowed books, and internet forums. I sense my involvement with experimental film has just begun, counting an arrival to Artists Television Access at just little over a year and half ago as the christening date. If there is any reason as to why I have been compelled to stick around, it’s not because of the money or the outcome, it’s because of the community. This idea is what remains central to Ramey’s text.

The arrival of Break the Machine comes with a sense of relief. Though experimental film may feel like a personal and intimate form once acquainted with, I imagine the discovery for most of us comes by way of unexpected revelation. The debate on how to evolve a form that accomplishes both autonomy and accessibility is ongoing, though for now it still remains largely un-institutionalized. Oddly enough, spending time with this text jogs memories of nebulous but formative experiences, perhaps irrelevant when discussing a textbook. However, a favorite memory of a smug professor reviewing my portfolio comes to mind, “You like Avant Garde? Yeah, I went through that phase. Maya Deren, right? Doesn’t make any money”. These sort of suggestions inspired within me a shrewd defensiveness on behalf of an innate interest for experimental film. It felt similar to a sentiment attributed to that of a conservative parent patronizing teenage ambitions. For a time I wondered, What makes the form legitimate? Is it even a form that seeks or requires validation? Is it a form that thrives because of its absence of need for institutional validation?

My initial excitement about the book stemmed from the notion that the production of an instructive textbook on experimental film in academia would prove wrong many educators and peers I’d encountered in a BFA program that placed most of its ideological faith in narrative and commercial filmmaking! What greater justification for legitimacy could there be for a subject than to be concretized in a textbook? Certainly history, math, physics, and narrative film all have textbooks, consequently they are subjects that are understood to be legitimate and worth studying. This quite petty ambition,realize, reveals my age. Once I calmed down from this lingering, youthful angst, I felt that “proving them wrong” was not the author’s intention.

I got down to reading. Break the Machine is structured in a way that any chapter can be accessed independently of each other in any order. I actually used it as a manual myself in the last month while making new work in a crunch. The book is an extensive centralized resource combining practical how-to’s and various theoretical interpretations. In the words of the author, Break the Machine is:

“a thinly veiled ethnography in the sense that it springs from interviews and participant observation and field writing conducted over half my life in the community of which I am a part.” (Ramey 2016)

What would one expect a textbook on experimental filmmaking to have? A chapter on cameraless filmmaking? Instruction on the JK Optical Printer? Hand processing? Ramey covers every bit of depth for each of these processes, with straight-from-the-source recipes by the likes Brian L. Frye and Polly Phenolly. The text exceeds expectations in taking on this encyclopedic nature with substantial chapters, for instance, one on how to make and customize your own optical printer, with Matt McWilliams providing his own open source code for building a sequencer. It is also truly DIY with Robert Schaller sharing his process for making fresh and unexposed stock, several recipes for eco-friendly processing at home, and sections in how to take glitch and data mashing into your own hands. Discussion of the handcrafted form is also contemplated from the perspective of its potential for venues in a gallery/museum installation or performative art.

What is particularly intriguing about Ramey’s exploration of DIY film making in neighboring genres is her brief acknowledgement of commodified art, a contrasting philosophy to DIY film which aspires to being independent of monetary value and accessible to the community. Hence, the debate on how to evolve a form that accomplishes both autonomy and accessibility is ongoing.

Theory and philosophy in Breaking the Machine also avoids academic pretentiousness, abandoning an objective and authoritative voice. Ideas as to why we make films, for whom, and for what impact comes from discussion with a wide range of makers. The initial question that Ramey asks of each subject is how they identify themselves: As an artist? Filmmaker? Professor? Curator? Scientist? The answer always varies, making difficult to put their efforts into one word. The placement of these interviews are at the conclusion of each chapter, after practical guidance and recipes for each topic in DIY filmmaking. This makes total sense, as I have often struggled with pedagogy, particularly in art, where the student is frequently bombarded with theories of others prior to her own intuitive exploration. Breaking the Machine pushes the student, rather, to play, make, and do first, with the abstract and theoretical developing as a result.

About the same time that my copy of Break the Machine made it to me, I was going through the archetypal contemplation of being a mid twenty-something who decides to move back in with her folks. Maybe I could save time and money for the sake of working on art, as the cost of living in the Bay Area is infamous, I thought to myself. The hours put in to afford rent leaves almost nothing left but exhaustion. But just as I was set on doing the humbling or embarrassing thing (however you want to call moving back in with your folks), I found a welcoming home at Other Cinema at Artists Television Access where I was being asked to join in on little things here and there, from artists I’ve long admired to those who I was just getting to know. In confidence I could say that it feels like we are all part of the same community. The sense of community challenges me to work on more art, practice and develop personal ethics, and feel those efforts shared and expanded upon. I can’t say that these efforts will necessarily achieve world peace or the next staple in the western canon, but we have the means to be our own little ecosystem outside of what is seemingly wrong and disturbing about the world.

On the ideas of rituals, Ramey concludes her text with this sentiment:

“[W]here we feed each other the nourishment that it takes to get on with our day-to-day lives where we are subjects, some of us princes, or even kings…[W]hen we artists come together and watch each other’s work and say it has value beyond what a market might give, or has ability to transmit a specific ideas or thought or emotion, when we ‘get’ each other’s work, then we have communitas.”(Ramey, 393-395).

I am quite excited and grateful for Ramey’s Break the Machine, as I already know I will be referencing it time and time again in my pursuits. It is a resource that empowers any maker to work self-reliantly and with several options, independent of industrial permission, and it was a resource that was made with the generosity of others sharing their knowledge and experiences in the hopes that it might be of benefit to someone else’s artistic freedom. It’s a testament to the fact that good intentions and honest practices still matter and inspire.

Links

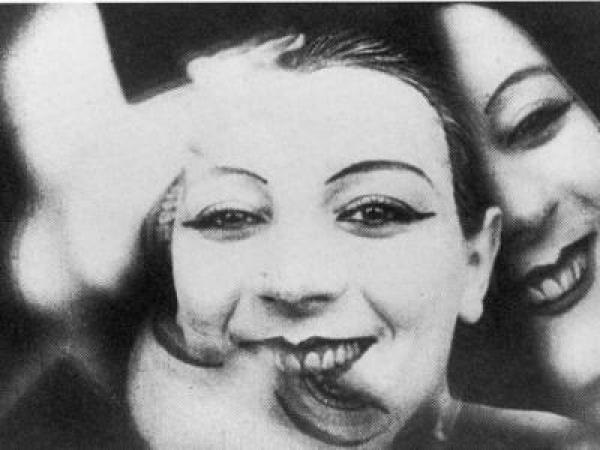

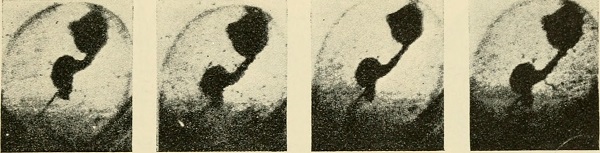

Dada woman and rat embryos from Wikicommons images.

Wow! Thanks Faith. Glad you found the book and that it worked for you.