by Kevin Obsatz

Where is, then, the articulation of cinema? Eisenstein, for example, said it’s the collision of two shots.

But it’s very strange that nobody ever said that it’s not between shots but between frames.

It’s between frames where cinema speaks.

– Peter Kubelka, in an interview with Jonas Mekas, 1967.

In 2004 I briefly worked as a projectionist-in-training at Crown Block E Multiplex 15 Theaters. It was a strange job at a strange time, both for me personally and for the whole industry of theatrical film distribution. The theater was almost new, built as part of a massive and ill-fated entertainment complex in downtown Minneapolis, and it was doomed from the start, open for only about a decade before closing and sitting vacant, until it was finally turned into some kind of health care facility.

In 2004, Netflix had not yet started streaming video (that came in 2007), Blockbuster and Hollywood Video were still relatively strong, and Avatar (released in 2009) had not yet precipitated the massive shift to digital theatrical projection in order to accommodate 3D movies. All of the films that came through Block E at that point were still presented on 35mm prints, which would be shipped in heavy 45 pound canisters that arrived on Thursdays to be prepped for their Friday premieres.

35mm film, projected at 24 frames per second, passes through the projector at a rate of 90 feet per minute, so a 35mm feature film print would be roughly a mile and a half long, completely unspooled. They generally shipped in six separate reels of about 15 minutes each, which at the multiplex were spliced together by a projectionist and loaded onto one gigantic platter.

35mm film, projected at 24 frames per second, passes through the projector at a rate of 90 feet per minute, so a 35mm feature film print would be roughly a mile and a half long, completely unspooled. They generally shipped in six separate reels of about 15 minutes each, which at the multiplex were spliced together by a projectionist and loaded onto one gigantic platter.

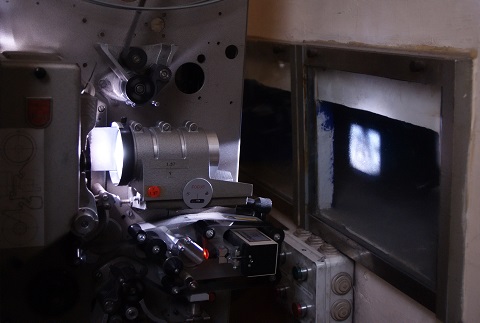

After the prints were assembled, though, the job of multiplex projectionist in 2004 was almost entirely automated. Minding the projectors involved threading the film through the sprockets and onto the takeup platter, pressing the “start” button, and peeking through the window to make sure the image was properly framed and in focus. These tasks for each projector and screen took no more than five minutes, so a shift was largely spent circumnavigating the long, narrow, nearly featureless hallway of the projection “booth” (almost a whole city block in circumference) and tracking the schedule of start times for all 15 screens.

The job entailed a fair amount of responsibility, a little actual skill, and paid a resoundingly disappointing, non-unionized $8/hr.

~~~

I only spliced together a few prints in my brief tenure at that job, so my interaction with 35mm film was fairly limited, but one particular moment at the splicing table stands out. I was putting together the reels of “Before Sunset” by Richard Linklater, looking for the edit point between two shots. The entire film is basically a long conversation between Ethan Hawke and Julie Delpy. So, nearly every frame in the film print is either a closeup of Ethan, a closeup of Julie, or a two-shot of both of them.

At a rate of 90 feet of film per minute of screen time, each shot in that film just goes on and on and on and on. And the frames themselves aren’t that interesting, or that different, one from the next: Ethan ethan ethan ethan ethan ethan: one minute of Ethan is over 2000 individual frames, and even if he were the BEST ACTOR EVER, still, the only thing really happening in each of those frames is his mouth moving, his eyes blinking.

Staring at hundreds of thousands of nearly identical frames of Ethan and Julie’s mouths moving, right then and there, I fell out of love with narrative cinema a little bit. It seemed like a waste of potential, of frames; if the difference from frame to frame was going to be so incredibly subtle and minimal and repetitive.

Which isn’t to say that I wanted more action, more explosions, Ethan is really a super spy and Julie is there to seduce him to get her hands on the microchip to avert global nuclear disaster… I also don’t think it’s a question of attention span per se. It’s about using the medium, this incredibly information-rich and high-resolution and vivid and versatile substance of the moving image, in all of its glory, to DO something, to MOVE, to articulate with light and shadow and color and and texture… instead of these two people just sitting there, frame following frame following frame, foot after foot, minute after minute.

My menial projectionist job was mostly a brainless and solitary slog, insert tab into slot, press button, call if anything goes wrong – but at least there was a very specific physical labor involved. The prints were a mile and a half long, and heavy, and the material was delicate enough to scratch or tear if it wasn’t handled carefully. Shipping prints all around the world cost a lot of money, and required effort and energy, loading them onto and off of trucks and planes, wheeling them down those long hallways, blasting high wattage light through the frames onto a screen for an audience.

Film prints degrade over time, too: maybe that’s obvious or maybe it’s not anymore. You can tell whether you’re watching a new print or an old one, they fade and soften, somehow the bright light knocks out some of the color density gradually over time, dulling the sharp edges, the beginnings and ends of reels accumulating scratches and dust. Screenings at our local repertory house, about a mile from Block E (now also closed and turned into condos) sometimes involved the film breaking in the middle, the lights coming up and the audience sitting uncomfortably, mid-narrative, some of us imagining the quick and stressful work of re-splicing going on hurriedly in the booth, hoping the print and our cinematic experience would be promptly salvaged by the heroic projectionist.

~~~

Much earlier in the life of Before Sunset, when Richard and Ethan and Julie got together to shoot those scenes, I think there was probably a similar awareness, on some level, of the hundreds of feet spooling through the camera and past the film gate, light coming in through the lens and striking the negative for a fraction of a second at a time. Most 35mm motion picture cameras only hold a thousand feet, or about eleven minutes, so when filming a long conversation, it’s important to know how much film is left, how many takes you can do before reloading, how many feet you’re sending off to the lab, how much you shot that day. Length in terms of duration and length in terms of distance have a direct, concrete relationship. Even on a big budget film, the quantity of footage being used is carefully tracked and discussed by the director, producer, cinematographer and camera department.

This was certainly still true when I was in film school (1997-2001), before the digital transition began: we had very specific allocations of film stock to use for each project, that limitation was built into the process at a fundamental level. Maybe all of this is curmudgeonly reminiscence about the good old days – if so, so be it – but we were careful because we had to be. There was an adrenaline surge when we started “rolling” which was felt by the person with their finger on the camera’s trigger, the actors in front of the lens, everyone on set. You could hear the whir of the motor and feel the vibration of the spinning shutter. These frames are precious, we have a limited number of opportunities to get this, only so many feet to work with.

When all is said and done, digital production can be provisionally cheaper than film production, but its primary appeal, I think, is that it offers an illusion of frictionless-ness. The digital files (still referred to as “footage”) can move around more seamlessly, from hard drive to hard drive. Theoretically weightless, this media can travel through wires and through the air, uploaded and downloaded by different technicians. Digital media takes up no space, except in the sense of gigabytes of storage, and these are pretty ethereal themselves… how much does a terabyte weigh these days? Even if you succeed in exactly quantifying the weight and capacity of a drive, it’ll change again in a matter of months anyway.

Film is a hassle, involving chemicals and labs and prints and trucking and shipping and underpaid, under-trained technicians in projection booths working for near-minimum wage with not much more than a razor blade and clear tape to put the films together. Working with film requires emotional investment and care, concern about proper exposure and light leaks, worry about scratches and tears and dust… not to mention the sheer time and effort expended just moving a film print across the country, across the projection booth, or even from one reel onto another.

But maybe there’s some value to that friction, that weight, that heft and labor and time and inefficiency.

I think that we are too readily seduced by the fantasy of frictionless digital capture. Moving images seem to cost nothing, weigh nothing, take up no space. They offer an appealing illusion of limitlessness – life itself in the form of “content” seems to proliferate as it is captured, diffracted by different lenses and perspectives, exponentially increased by multi-camera shoots, widened by panoramic stitching and fish-eye lenses, made waterproof and indestructible by extreme sports accessories.

The thing is, we are not indestructible or infinite. Vast quantities of digital media are easy to accumulate. Media can be hoarded, archived forever, kept safe and backed up to the immortal cloud. Digital media is cheap, and getting cheaper all the time. You can generate as much of it as you want – the question is, will you ever get around to watching it all?

Life is not frictionless, art-making is certainly not frictionless. We are inefficient, limited, hopelessly mortal creatures, and I believe that knowledge of our finitude is the very stuff from which art is made. There are certainly valid reasons to choose digital technology as an artist, but efficiency, convenience and ease are not, in my experience, conducive to good art.

When I make a film (usually 16mm, sometimes super-8, never yet 35mm), I always know how much footage I will have to work with. I’m not always careful with it, but I’m unceasingly aware that I will run out, that every shot is a specific choice, that every frame recorded takes something that is pure potential, unexposed, blank, and makes a sort of micro-commitment in that tiny space. I may not ultimately decide to use that particular shot or that frame, but I don’t have the digital luxury of reformatting it and recording over it.

~~~

My goal here is not to be prescriptive, to tell anyone else how they should make art. I have found a process that works for me, which will no doubt continue to change and evolve, and which will no doubt continue to include both film and digital technologies.

I’m merely bored with the standard arguments between film and digital, that film is inherently better, that digital is inherently better, or that they are essentially the same and that any distinction between them is fetishistic.

I think the claim that film is essentially or inherently unique does make sense, if you are actually handling it, if its length and breadth and weight and chemical composition are impacting your choices of how to work as a filmmaker, when to shoot, when to wait. Film is important as film if you are in close proximity to it, in relationship with it, either in the projection booth or with your hands on the camera. Film is an inconvenient hassle, it’s heavy and bulky, a medium born in an artisanal age and refined during an industrial age. It is made of organic compounds and chemicals and minerals. It is defined by its limitations, its fragility, its risks, its fricative and finite nature.

There is potential, in the digital realm, for the exploration of other sorts of limitations. But if we try to ignore or gloss over the limitations of the digital – believing that the technology is somehow setting us free into a wonderland of boundless creative flow, we’re willfully misunderstanding the medium, and doing a disservice to it and to ourselves as artists.

~~~

I only lasted about six weeks as a projectionist-in-training. I was too sloppy and careless for the job, I didn’t want to be there badly enough to be really diligent and give the tasks of the projectionist the careful attention they required. It was lonely up in that long rectangular hallway during those long shifts, with only the hum of the projectors to keep me company. Looking out the little booth windows at all the people settling in to watch their movies together made me feel like a ghost.

For multiplex movies, digital projection certainly makes sense – nobody should ever again have endure the existential crisis of being confronted by thousands upon thousands of tiny Ethan Hawkes staring accusingly up at you, like I did. On a vast, industrial scale of either production or distribution, I don’t know if it really matters what the stuff is, the medium, the material running through the cameras and projectors, the chemical baths and the algorithms and the shipping canisters and the hard drives.

The economic conversation about jobs, and the aesthetic conversation about the look, both seem to me to be outside of the process itself, the act of making a movie, capturing moving images, working with them and sharing them.

When it comes right down to it, it seems to me that the only people who ultimately have a stake in the matter are the ones who want to work with these tools directly, to try to make something intimate and up-close and personal, about life in this world in all of its messy, fragile, impermanent incompleteness. Film is a profoundly beautiful and challenging medium for artists who are interested in engaging the moving image with their own two hands, moment by moment, foot by foot, frame by frame.

If you haven’t tried working with film in that way, I highly recommend it – it’s pretty special.

1 comment for “PART 2: The Loneliness of the Multiplex Projectionist”