by Eric Stewart

Introduction

Contained in every space is a social fabric whose threads weave themselves in time; this weaving is generally called history. Prior to the official birth of cinema in the 19th century, moving pictures and projected light encompassed a genre known as “Philosophical Toys”, whose stroboscopic images appeared to recreate vision and experience. It was thought that because these images are so close to sight that the mechanics surrounding this simulated vision must then be close to the workings of perception and the mind. In this apparent similarity is a playground for natural philosophy, where the space between images is the space between thought.

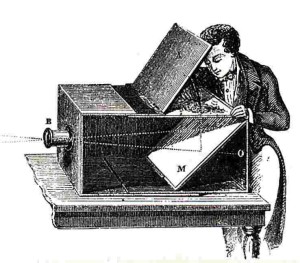

Grandfathering philosophical toys was the Camera Obscura, an optical arrangement known of since ancient times, in which light is focused into a darkened space through a small opening. Later when this focused light was captured chemically the process was generally called photography and, prior to 1830, when captured by hand was generally called drawing and painting. This place for the careful viewing of focused light is a reminder that visual representation is partly architectural and, moreover, that the projection of visual space is reliant on distance. The relationship between the lens and a focal point (the screen) mirrors that of spectator and subject. The camera as a reflexive instrument makes the lens as much mirror as a window.

1.

Like wind filling a sail, a photograph discloses and captures a momentary energy moving through space. When looking at the space depicted in a photograph our attention is usually focused on the external dimensions of the camera, the place outside the lens, which the picture seeks to represent – the subject matter. Audiences generally want to know and understand this subject, the object of focus, the thing being looked at. But what happens when we reverse our view and look into the space of the darkened antechamber of the camera itself? What social fabrics are contained in that dark space of projection, whose only purpose is the focusing of light?

When Henry Fox Talbot published his findings on photography he did so in a book called “The Pencil of Nature.” Like the gentle turning of fall leaves or a child burning ants beneath a magnifying glass, light can write itself into surfaces in ways both violent and subtle. Light not only spills across surfaces but also transcends distance, moving through and imbuing space. To explain the movement of light through space it was once proposed that space contained a medium called the Aether. Like a tidal wave passing through the ocean, light too, or so it was thought, must propagate through something. Aether was this something, the stuff of space itself.

The theory of Aether describes existence as a condition of suspense, telling us that the state of being is one held taught within the confines of a massive lighthouse whereby space is constituted by the curved membrane of the lighthouse’s Fresnel lens. Aether paints the world as perched in a watchtower on the edge of a continent looking out over a limitless coast into a boundless field of fluid energy. As we peer into the dark from our thin membrane of focus, space itself is something like the bellows of a camera.

Displacing Aether was Einstein’s “Theory of Relativity”. In his youth Einstein wondered what light would look like if one were able to travel next to it, like a passenger on a parallel subway car, Einstein asked “What would the face of light look like if you could ride next to it and wave hello?” All photography aspires to this question: what is it to halt light?

No longer useful as a description of reality Aether remains useful as a thought experiment, because ours is a world under glass, a world mediated through reflective devices and transmitted images. Aether considers what it means to live in a world permeated and held by a translucent substance which only light transcends.

2.

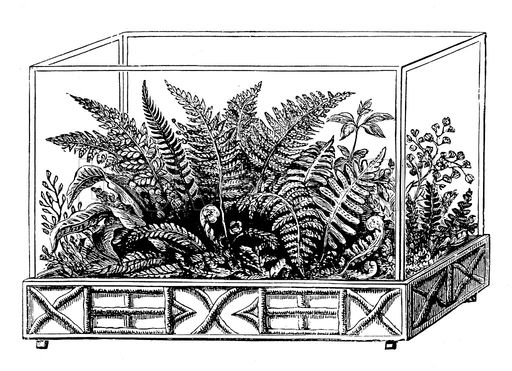

The vitrine is an enclosure and the telescope a connective tissue. Because glass permits the passing of light to the exclusion of all else it is both a prison and a portal. When Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward began growing plants in enclosed glass containers he called “Wardian Cases”, he did so to protect his fern and moth specimens from the industrial pollution of 19th century London. Ward was an English physician and amateur botanist whose publication “On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Containers” described his experiments under glass as the simulation of nature in a container.

Once placed on boats bound for other ecosystems, the cases enabled a form of movement previously unimaginable: the transportation of living plants across the world’s oceans. Long distance botanical trade was once restricted to seeds and dried cuttings, but because the case safely shielded plants from the ocean air’s cold temperatures, salt spray, and provided a regenerating supply of fresh water, entire living plants were able to be brought from the South Pacific and North America into Europe for the first time. The Wardian Case revolutionized botany and horticulture to such an extent that Sir William Hooker, director of Kew Gardens, London 1841-1865, remarked that the case had imported into London six times as many plants in its first decade and a half of use than the entire previous century[1].

The Wardian Case formed a kind of psuedo-cinematic space where the “simulation of nature in a container”, mirrored the drive of all the representative arts from cartography to painting: the desire to recreate the world in miniature.

The Wardian Case was a living diorama and alongside the large botanical glasshouses that it inspired forms a tableaux vivant of the natural world. The case extended landscape painting into the realm of experience to create an image of a foreign and distant world. These glass enclosures were theatres of not just botanical spectacle but, with their large glass panes and iron reinforcements, were also monuments to the power and novelty of industrial engineering and the aristocracy which it served.

The Palm House at Kew Gardens is a large Victorian Glass building modeled after the London World’s Fair’s Crystal Palace in Hyde Park and also mysteriously resembles the hull of an overturned boat. In many ways the botanical glasshouse can be thought of as the antithesis of the Camera Obscura. While a camera is an opaque enclosure and a black cube with a single point of focus, the glass house is a transparent architecture; a completely illuminated space with infinite points of focus. However, similar to the pseudo-cinematic space of the Wardian Case, glasshouses conduct many of the features performed by the cinema namely the recreation of time and space within a frame. From an aerial perspective the glasshouse resembles the Black Maria Studio of Thomas Edison, which with its black walls and glass ceiling created an enclosure filled with sunlight intended for the capturing of reality.

3.

In “Digital Mana”[2] Marcus Boon describes the infinite in both transcendental and scientific terms. Existing beyond perception, conceptualization, and imagination the infinite defies human understanding; to experience the infinite is to experience the sublime. Conflating infinity with divinity symbolizes the act of creation itself and becomes a stand-in for nature; both human, ecological and philosophical. Symbolically, the infinite, forms the well from which both language and representation are drawn. Through controlling representations of infinity, and representation of nature, systems of Power– monarchical, aristocratic and/or democratic– give themselves justification by virtue of being closely aligned with the natural. “At infinity, aesthetics, mathematics, and theology meet on a unified plane whose grandeur and perfection symbolizes God”[3].

Since the rediscovery of linear perspective during the Renaissance, infinity came to be represented in the vanishing point, [a point located on an imaginary horizon.] Architecture and urban planning both reinforce and reference single-point linear perspective and project an optical space not found in nature, but which is instead theorized from optical experiments onto our collective, lived urban and rural experience. The formal rows of hedges and trees at Kew Gardens extend this logic of linearity and like the gardens at Versaille they weave infinity, sovereignty, and colonialism into a nexus, where the stacking of glass and adherence to pseudo-Euclidean geometry monumentalizes Power. Projected through space are areas of non-productive nature for the enjoyment of a privileged elite. These spaces quarantine raw capital and this control over landscape forms a psychogeographic domain testifying to their creators’ vast and decadent ability to collect.

Cartography, landscape painting and documentary enact Power pictorially. There is a reason the British Empire so studiously mapped, charted, journaled, painted and pictured the New World. It was not only a logistical way to enact Imperialism but also a symbolic way of outlining ownership and control, through projecting lines of Power through latitude, longitude and language.

Thus, the botanical garden, stocked with fauna from the world over, mimes the same gesture as did photography: to move beyond representation and enter into the realm of the compellingly complete simulation in order to become the phantom that convinces us of its authenticity.

Just as the New World was domesticated and its commodities sailed along latitudes of control, so too was the garden and optical space domesticated, all in an Enlightenment effort to demonstrate humanity’s control over nature. The palm tree growing in the United Kingdom demonstrates the Empire’s ability to re-make the natural world and seemingly to rewrite and replace the laws of nature with the laws governing capital.

HARBOUR from Eric Stewart on Vimeo.

Notes:

[1] From “The Remarkable Case of Dr. Ward” in The Telegraph 1/19/2002

[1] “Digital Mana” by Marcus Boon

[2] “Mirrors of Infinity” pg. 59

The comparison of making films and creating self-contained terrariums is very interesting… Makes me think about how the visual artist and especially filmmaker “grows” a reality for others to engage with — both in an organic and heavily controlled/”colonized” way.