by Gerry Fialka and Will Nediger

Like Craig Baldwin, Raoul Peck incites new questions to ponder with challenging juxtapositions like the lovely song Fascination (from Billy Wilder’s Love In The Afternoon) with footage of Rodney King’s beating. James Baldwin is heard saying, “It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro. The real question is what is going to happen to this country.

“I want to be Adam Curtis when I grow up.” – Errol Morris

John Waters and Andy Warhol are Jack Smith wannabes. Godfrey Reggio is a Hilary Harris wannabe. See the “Wannabe List” below for many more examples. In a surprising number of cases, artists want to be their heroes and, at the same time, they try to resist being their heroes. As Louis Alvarez said, “You create what you resist,” and, as Carl Jung observed, “What you resist persists.” Artists want that creativity that comes from struggling with similar impressive work that has come before. They want for their art work to escape the shadow of these powerful influences, to go forth and persist in the world on its own merits, and to take on a fresh new life of its own in the minds of its viewers. Amid this jujitsu dance of enemies and influences, how do viewers of art and film make meaning? As Marshall McLuhan might say, the user needs to become the content, throwing him or herself into the middle of the melee. In the process the viewer moves beyond both the artist and beyond the influences that shaped, inspired, and hampered the artist.

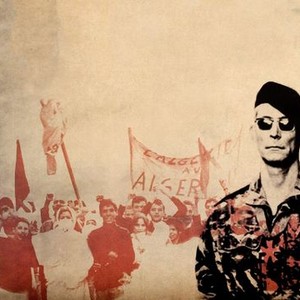

Clearly, a work of art holds no one meaning. Its meaning is made and remade by viewers according to their perspectives and needs. When asked what The Battle of Algiers (1966) teaches people, the director Gillo Pontecorvo responded: “How to make a film.” That is, it’s often viewed as a landmark political film about armed resistance used to overthrow colonial power, but it’s more important as a landmark film, a fake documentary onto which viewers project their own politics. It has been championed by guerrilla movements and governments alike. At a 2016 Directors Guild of America panel, author Sohail Daulatzai remarked that some people watch The Battle of Algiers now and think it’s an anti-Muslim film.

Because individualized perspectives can lead to such narrow, time-bound, or partisan misreadings of works of art, a Zen approach can hold great value, since it actively promotes having no particular point of view. This approach calls for a viewer to detach, suspend judgment, and be open to the big picture. While not appropriate as a framework for all viewing, in some instances, it is the best or only one. The collage documentaries of Adam Curtis, for example, seem to inspire—or confuse—people into taking this large, open-ended Zen view. He’s been adopted by the left (see his appearance on the leftist podcast Chapo Trap House), but Curtis doesn’t consider himself a leftist; he’s skeptical of utopian schemes and totalizing ideologies of all sorts. But that doesn’t mean his films don’t have a point of view, only that they resist being able to be labeled or sorted, for instance with binary terms like left and right, or true to life and not true to life.

Curtis reminds us that the line between realism and art is always being delicately navigated by documentary filmmakers, in a way that affects how their work is viewed. Just ask Frederick Wiseman, a kindred documentarian whose films have been described as cinema vérité, though he considers that phrase a contradiction in terms. Wiseman calls his documentaries “reality fiction.” To make films that have elements of both reality and fiction, an artist much be able to suspend judgment, to keep that Zen open mind, and so must the viewer. Yet both artists and viewers are always very much complex products of their particular blends of identities, backgrounds, and influences. When asked in a 2016 interview about how he became adept at suspending judgement in this essential way, Wiseman said, “I am a New Englander, Puritan, and Jewish.”

In line with Wiseman’s provocative term “reality fiction,” other documentary filmmakers have devised similarly nuanced ways to express the delicate balance of elements they strike in their work—terms which provide keys to how they want viewers to see their work. Allan King describes his work as “actuality dramas,” and Richard Leacock calls his, “historical fantasies.” Significantly, this harnessing of conflicting and potentially dangerous elements corresponds to the way that artists blend the work of their influences into their own work, with these influences seen as both friend and enemy.

The relationship of enemy is an oddly intimate one, as has often been remarked upon. The Dalai Lama has said, “In the practice of tolerance, one’s enemy is the best teacher.” In a similar vein, Zen philosopher and entertainer Alan Watts pointed out that, “If you acknowledge your enemy, you empower them.” “Bobcat” Goldthwait says simply, “You are what you hate.” And Francis Ford Coppola has reflected on the famous rule guiding the worlds of samurais and the mob alike: “Keep your friends close and your enemies closer.” From that principle we got the popular coinage “frenemies.” It is not too big of a stretch to propose that to artists, their influences—including whatever outside social causes stimulate and activate them—are like frenemies. Influences, or bad situations in the world, such as form the subjects of some documentary films, are not just sources of danger and conflict. They can call forth creativity, the best one has to offer. These sparks to action must be simultaneously learned from and resisted, assimilated and avoided, loved and surpassed, carefully recorded and made into transcendent art.

Sometimes this artistic dance of embracing and resisting a person or cause is figurative, and sometimes it is literal—that is, a part of literal resistance being put up against an antagonistic force that is inspiring their best work. At Standing Rock, “artist Cannupa Hanska Luger created dozens of mirrored shields from Masonite and reflective vinyl that were as much protective devices for frontline protesters as they were bright works of sculpture” (Los Angeles Times, 1-8-17). Activist Doug McLean says, “When I worked at Greenpeace, there was the concept that it was founded on which was the Quaker principle of bearing witness. The best journalists and the best artists are the ones who get the most out of the way and are simply a lens.” Again, the line between accurate, true-life documentary representation and the creation of art is hard to find—or impossible, non-existent.

Returning to the phenomenon of wannabes and the mystic threads that interconnect them, experimental filmmaker Craig Baldwin is a Bruce Conner and Jean-Luc Godard as CovertAction Bulletin wannabe. Rodney Ascher is a Craig Baldwin wannabe, whose film Room 237 was reviewed in both Artforum and People Magazine. Could director Raoul Peck be another stellar Craig Baldwin wannabe with his cinematic séance I Am Not Your Negro? In this intense, emotional essay film, Peck combines the words of James Baldwin (no relation to Craig) with a collage of alarming Ferguson footage, Sidney Poitier films, and clips of Doris Day and Ray Charles. The result evokes Frank Zappa’s question, “Hey, you know something people? I’m not black, but there’s a whole lots a times, I wish I could say I’m not white.” Peck includes a clip of the ever-curious James Baldwin talking on The Dick Cavett Show (a rare instance in the history of cinema of the screenwriter actually talking on screen). Elsewhere in the film, Baldwin says, “You cannot lynch me and keep me in ghettos without becoming something monstrous yourselves. And furthermore, you give me a terrifying advantage: you never had to look at me; I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me. Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

The juxtaposing of the wannabe hero (the artist) and the enemy (the influence; the subject matter or social issue that sparks the act of creation) leads to the question: “What can one do about an observed problem in the world?” Make a film? Write an essay? Not make a film? Not write an essay? As Maurice Blanchot observes, “The answer is the disease, the misfortune, of the question.” In his review in The Guardian (10-20-16), Jordan Hoffman writes, “I Am Not Your Negro’s specifics are only intermittent, like reporting on different reactions between white and black audiences during Sidney Poitier films. By and large this film concerns itself with the greater philosophy of why groups in power behave the way they do. This might be the only movie about race relations I’ve ever seen that adequately explains—with sympathy—the root causes of a complacent white American mindset. And it took a black writer and director to do it…I Am Not Your Negro isn’t a special interest title, it is a film.”

Like Craig Baldwin, Raoul Peck incites new questions to ponder with challenging juxtapositions like the lovely song Fascination (from Billy Wilder’s Love In The Afternoon) with footage of Rodney King’s beating. James Baldwin is heard saying, “It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro. The real question is what is going to happen to this country.”

Playwright Bertolt Brecht believed “Art is not a mirror held up to reality. Art is a hammer with which to shape it.” High aspiration? McLuhan probed the hidden psychic effects of the words making and matching (mirroring). He wrote: “Most people have the idea of communication as something matching between what is said and what is understood. In actual fact, communication is making. The person who sees or heeds or hears is engaged in making a response to a situation which is mostly of his own fictional invention. What these critics [F. C. Bartlett and I. A. Richards] reveal is that the mystery of communication is the art of making.”

McLuhan challenges us to have the courage to: “Carefully make plans, then do the opposite.”

How can the oppressed resist by making the oppressors see themselves in the mirror? How can two fakes make a truth? How can one reverently satirize what one loves the most? “One never knows, do one?” asks Fats Waller. Good question? Ruin it with an answer? What we know for sure is that resistance through disruption can build new wannabes, and, as well, can bypass the need to create the “wannabes” syndrome. Movements can organize new strategies, turning breakdowns into breakthroughs and turning rejection into redirection.

Gerry Fialka and Will Nediger are currently writing a book on the future of the history of avant-garde film. Laughtears.com Please read the Menippean satirized version of this essay: http://laughtears.com/wannabe.html

References:

wannabe (n.) 1981, originally American English surfer slang, from casual pronunciation of want to be; popularized c. 1984 in reference to female fans of pop singer Madonna.

jujitsu (n.) also ju-jitsu, 1875, from Japanese jujutsu, from ju “softness, gentleness” (from Chinese jou “soft, gentle”) + jutsu “art, science,” from Chinese shu, shut.

Wannabe List:

Note: Please don’t take the following wannabe list too seriously. We’re serious about not being serious.

We were anxious to get publisher Colonel Baldwin’s reaction to this exercise. To our surprise, Craig responded: “The wannabe list is a wonderful exercise in film criticism and philosophy!!”

Richard Linklater is a James Benning & Robert Bresson wannabe (especially his very first film It’s Impossible To Learn To Plow by Reading Books)

The Coen Brothers – Homer as Preston Sturges wannabes

Ken Loach – lefty Mike Leigh

David Lynch – Painter Francis Bacon as Luis Buñuel

Christopher Nolan – Charles Dickens as Stanley Kubrick

Douglas Trumbull & Stanley Kubrick – Franz Kafka & HP Lovecraft as Elia Kazan & Jordan Belson

Morgan Fisher – Robert Bresson as a school clock

George Lucas – Buck Rogers as Joseph Campbell

Joseph Campbell – Finnegans Wake as James George Frazer

Finnegans Wake – Henrik Ibsen & Tristram Shandy as radio & cinema & language about language

Stan Brakhage – Gertrude Stein as Jackson Pollock

Jem Cohen – Chris Marker as Walter Benjamin & Ludwig Wittgenstein

Bill Brown – James Benning as Jacques Derrida

Ben Russell – Michel Foucault & Maurice Merleau-Ponty as Werner Herzog

Woody Allen – Ingmar Bergman as Groucho Marx

Terrence Malick – Huck Finn & Erik Satie as Andrei Tarkovsky

Adam Curtis (BBC) – Arthur Lipsett (NFB) & John Dos Passos & Erik Durschmied as Robert Rauschenberg

Curtis Harrington – Edgar Allan Poe as cinema

Sam Mendes – Nathaniel Dorsky as the living end

Ryan Trecartin – John Waters as Paul McCarthy

Frederick Wiseman – Henry James as Charlie Chaplin

Peter Greenaway – Jorge Borges & James Joyce as Neo-Classical art & Hollis Frampton

Coleman Miller – Tex Avery & Ernie Kovacs as Bruce Conner’s favorite film

Will Nediger – Tony Conrad as Will Shortz

Gerry Fialka – Land Without Bread & The Gleaners and I as the MC5 meet Sun Ra at The Shaggs picnic

This essay – Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematograph as Cecil Taylor as Rube Goldberg

Finally our impulse to view racist actions as a thing of the past has been stifled. I Am Not Your Negro connects them seamlessly to the political climate we are living in now, using the commentary of america’s last great writer on race relations, James Baldwin. Using virtuoso collage style editing, raoul peck creates an artwork that, I would argue, does what all great art ought to do: force the audience to arrive at a set of moral perspectives by way of intellectual rigor. We vitally need more mainstream films like I Am Not Your Negro not only to challenge our film-viewing intellect, but also to make us consider our country’s most uncomfortable public issue: race.

I appreciated Gerry’s essay, and do encourage readers to check out the satirized version also- http://laughtears.com/wannabe.html

Not serious, eh? Too Bad For You!

Even with the enormous mass of media any present-day adult is exposed to, it would be impossible for most anyone without an eidetic memory to know where a visual reference originated. And those of us who have for so long absorbed a wide range of visual / aural / textual Kultur find it even harder to know for sure whether any idea we have is an original one – or to what degree it’s been influenced by others.

This phenomenon can produce a fear of influence in artists that has been seen for many decades now. Lots of jazz musicians refused to listen to jazz lest they be accused of lifting others’ riffs…and listening to the likes of classical and folk instead, they inevitably were swayed in those directions. I know filmmakers who also avoided any influence for many years in order to preserve what they thought were their own ‘unsullied’ visions, and I’m sure the same has been true for some writers.

No artist wants to be accused of plagiarism, especially when they truly had no intent to steal someone else’s stuff.

But in this era of total five-finger-discount appropriation, ya gotta wonder whether such questions matter anymore?

Does anyone really give a hoot hoo influences hoom ?

And in the era of hypernormalisation and ‘alternative facts’, does Intellectual Property exist? Is art a Valuable Truth?

I know you like quotes, Gerry, so here’s one from ol’ Pablo P., one of the first publicity-hound artists who learned to play the art critics’ world like a Strad:

“We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies.”