On March 22nd, 2014, David Cox will be introducing Other Cinema’s screening of Zizek: A Pervert’s Guide to Ideology!

This is not a technological determinist essay about wearable technologies and AR, and its authors are not technologically “determinist.” Nor do we say, as the liberal position would have it, that new technologies have “good uses” and “bad uses.” Rather, we take the politicized, artistic position that technologies of seeing and perception have potentially much greater good than they might simply as the proprietary products of neoliberal, capitalist economic “creativity” and that technologies alone are not the determinants of an absolute or universal “social good.” In this context, it is desirable to look at a provocative history of experimental research on wearable technologies and their relation to AR. The best and most poignant work described by us has reflected the impulses of technologically social and political agendas—placing code, parts, systems, and tools into the hands of the people: the artists, students, intellectual laborers, scientists, and others, engaged in their use. Furthermore, the design agendas allow people to self-organize and self-actualize their experience. We take the position that the hardware is not neutral but that it is being invented; that anyone can build an inexpensive wearable computer; moreover that the ideas of software aren’t at all neutral. Wearable computing, of the kind explored here, is conceptually the “punk rock” strain of wearability, and has been for over thirty years. In the research spectrum which straddles military use, the development of Google Glass, and a range of post-Hollywood “implications” for the technologies, these wearable experiences represent a margin. Generally speaking, until now, in terms of how one engaged with wearablility, it was either self-made or went untried. Now we have a new spectacle, that of the commercialized “glass” and it is to this reality that we are, in fact, speaking.

Explanation

Wearing computers are capable of mediating information and ideas between the wearer and the wearer’s environment in an intensely intimate and personal way. They do not need perforce to produce an individualist “me” mentality, nor contribute to war vision or isolationism. On the contrary, wearable computers can be designed to connect the wearer to his/her environment through the mediation of online interfaces, the Internet, web, AR information and through personal connectivity to others where possible. Wearable computers can also work off of autonomous social networks and servers, rather than using commercial cloud technologies which are designed for surveillance and data storage. Basically, wearable computers can be customized to fit the needs of the groups or persons that use them, especially when made by them.

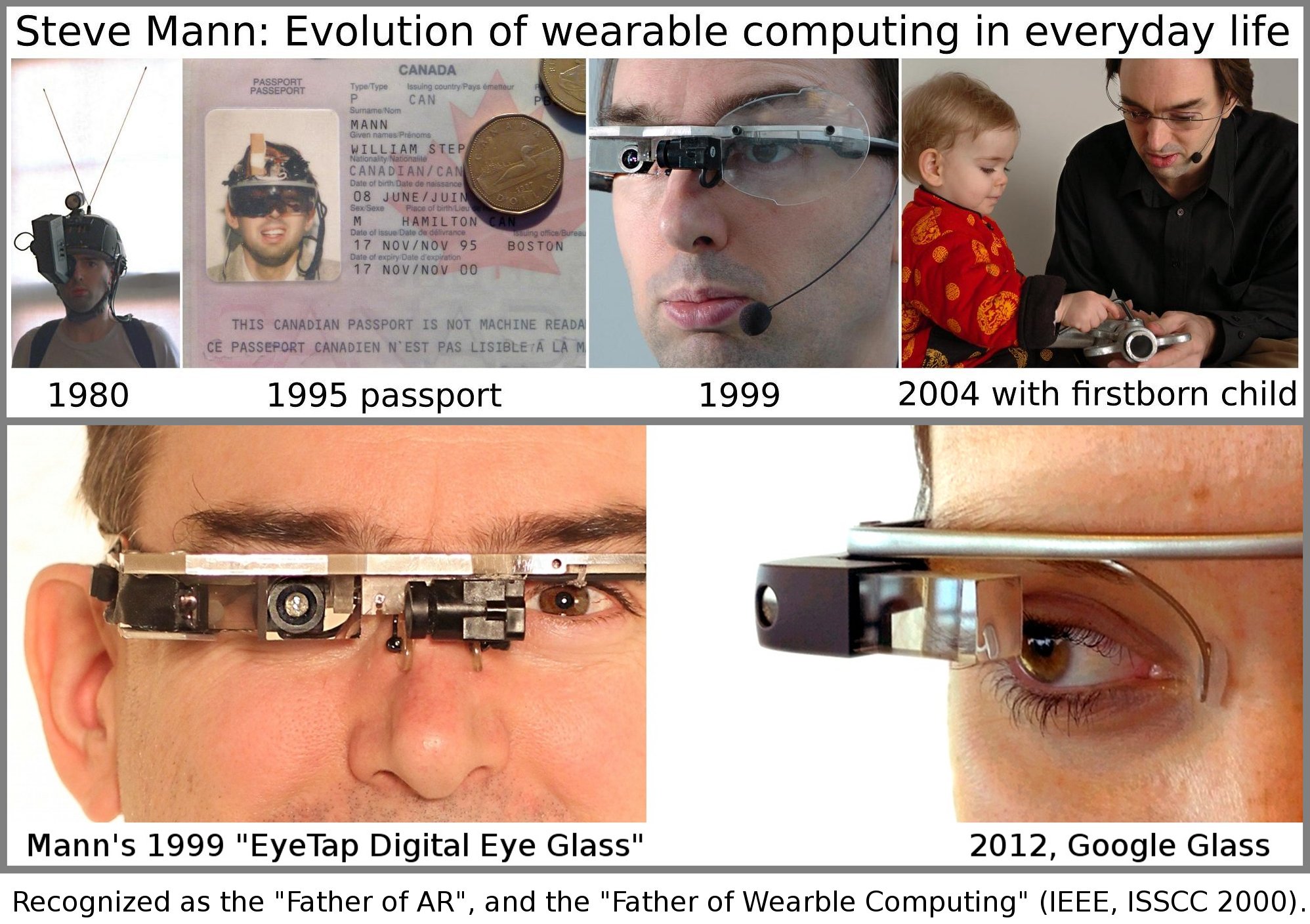

Google Glass does not own the concept of a popular wearable computer or a popular AR, and even if they were to “adapt” the best aspects of the display technology from the best and the brightest designers, they would probably fall short of what more can be done with such an instrument. First of all, the proprietary Google Glass device is not truly customizable. It is simply a more efficient way to use what is already “locked in” to social-media services. The Glass will facilitate the ever more efficient means of “social” reporting and selling one’s own life and that of everyone around you that is the “social media” zeitgeist of today’s consumer technoculture. A wearable computer that is based in open source and non-proprietary thinking already works against this “social” model of networked human perception. To enable, empower and facilitate, in what Toronto University wearables researcher and, arguably, father of wearable computing, Prof. Steve Mann calls souseveillance, or “seeing from below,” we must first start with non-proprietary thinking. In other words, the computer will be worn to gain control over, or reframe and reposition what is seen, recorded, stored and used, not simply to make the act of “wearing” and “seeing” benefit commercial interests and the machinations of the NSA.

Perception/Reception in Arts of Seeing

When Albrecht Dürer demonstrated via his 17th-century etchings how to draw in perspective, he did so by showing mechanisms that forced the student to view the world as made up of a series of single viewpoints. You had to look through a hole to see a small part of a mandolin, then draw that part, then move on to the next portion. This method encouraged the student to understand the world as a totality of multiple viewpoints, a principle which today underpins AR. Starting this year, the technology has become available to enable a wearable computer to “paint” a room with enough infrared beams for a 3D “camera” to “see” objects in front of it. Those objects can then be used to track the placement of virtual objects over them as a group of “overlays.” The pursuit of seeing the world as a multiplicity of view points has endured from Albrecht Durer to Space Glasses, the alternative to Google Glass, with Steve Mann as the Dürer of our time.

The notion of seeing the world as if it were a totality of singular points is, arguably, also a hallmark of the “universality” that we still live under—a singular vision converging on the human eye. It is also akin to the cybernetic feedback loop where everything converges back upon itself.

In the 1950s, the propaganda British War film The Dam Busters depicted a bombing raid on the German Rühr dam complex. The special bombs used in this raid needed to be dropped from a low altitude, and at an exact distance. In the film, the main character gets the idea to build a wooden “V” shaped device that enables the bombardier to line up two wooden pegs at the ends of the device with the ends of the dam he is aiming at. In that low tech example, the singular eye’s vision is “augmented” with the wooden pegs that stand-in for real objects, in this case, the physical extremities of a distant, but rapidly approaching bomb target. The wooden pegs act similarly to the idea of overlaid objects (mentioned above) that are tracked to real objects in an AR landscape enabled by wearable computers.

In the 1977 homage to The Dam Busters, Star Wars, George Lucas reproduces the wooden peg scene, this time using a small ‘targeting computer’ that lets Luke Skywalker know when it is time to fire his torpedo. Mediated vision, military seeing and the calculation of time, space and motion as addenda to human sight have been used in many popular films and even in experimental film performance when, for instance, images are projected on to objects or interfered with in some way. Of course, as Lucas’ film suggests, it is best to turn the computer off altogether, and use intuition. A good wearable computer is a combination of both—technology and intuition—the nearest thing altogether to being “one with one’s machine.”

Augmented and Mediated Reality

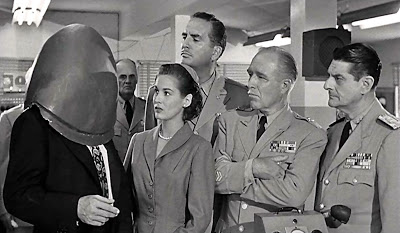

The alien’s helmet in Earth vs The Flying Saucers. The metal turns out to be fully transparent. Reality can be augmented.

In Earth Versus the Flying Saucers scientists discover that invading aliens wear helmets which let them see the world around them. From the outside the helmets appear solid but, from the inside, they are completely transparent, and can translate language. They are effectively real-time wearable language-translation devices with built-in head-mounted displays. Such “messing” with vision and the notion that wearing the device lessens the space between the wearer and the subject is much of the impetus behind augmented reality and wearable computing. Steve Mann’s Eyetap device actually utilizes the human eye to project light onto, turning its vision into a “screen” and making his body part of the machine.

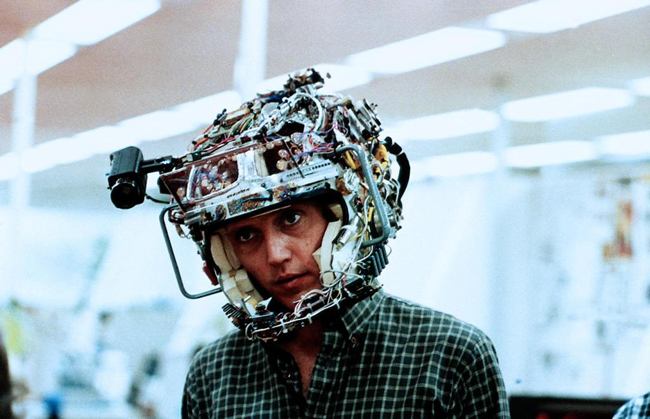

Heads-up! 1982 Douglas Trumbull film Brainstorm. A lovely parable about hackers overcoming militarists for control of a new technology of great promise for the future of the imagination. Chrisopher Walken dons the early version of the Brainstorm Headset.

The boardroom demo scene from Brainstorm. The zoned-out suits who have been investing in the Brainstorm technology finally get to wear the devices and have high-definition multi-sense recorded thoughts and experiences played back. The military are quick to see the Psych-War potential.

“The Ultimate Display,” Sutherland, I.E., Doug Sproull, Proceedings of IFIPS Congress 1965, New York, May 1965, Vol. 2, pp. 506-508.

In the 1982 film Brainstorm, directed by Douglas Trumbull, a high tech Silicon Valley research team have developed a headset that can record experiences directly onto tape. As they slowly perfect the technology, the headset shrinks to the size of a tiara. The recordings become more accurate. Someone decides to loop an orgasm and gets addicted to it. Soon seeing its potential for psychological warfare and counter-intelligence, the US military backers funding the project take it over from the liberal humanist scientists (the project leader is a brilliant woman) and tech engineers, who fight back with their hacking skills and expertise. It’s a great political conflict for our time. The actual acid trip-like Brainstorm scenes are worth seeing, but the relevance for wearables and AR is the notion of an advanced form of augmented consciousness, made possible with technologies that are synaptically connected to the body, which close the gap between nervous system and electronic networks and which are creatively re-purposed to transgress these boundaries. At the end of the film the team overcomes their enemy and is able to successfully record the moment of death itself, enabling the subject, who is alive, to die, without dying.

Headmounted Displays and Smart Devices

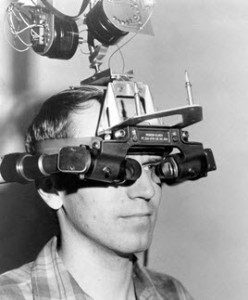

The development of the head-mounted display in the context of computers is the key feature of today’s wearable “glasses” and begins with early experimental systems such as “Sword of Damocles” developed by Ivan Sutherland in 1965. Sunderland’s system allowed the user to view 3D-generated computer graphics and to see those graphics as if they were in the same environment as the user. Closer to Virtual Reality than Augmented Reality, the significance of the Sword of Damocles system lies in its use of separate monitors, one for each eye, and the system of motion tracking. As the user turns his or her head, the content appears to move in relation with the motion of the head, accordingly. Sutherland is also known for his “sketchpad” program which was among the first computer graphics programs to enable the production of 3D graphics.

Today’s smart devices (phones, tablets, etc.) designed with touchscreens enable augmented reality or AR to exist in the palm of one’s hand. They come with a camera and with sensors like accelerometers, GPS, Wi-Fi cards, and cellphone receivers. These working together enable the user to access information about locations which appears to float in place relative to the actual geographical location. Nearby waypoints—points of interest—can appear relative to one’s position simply by holding up the phone or tablet.

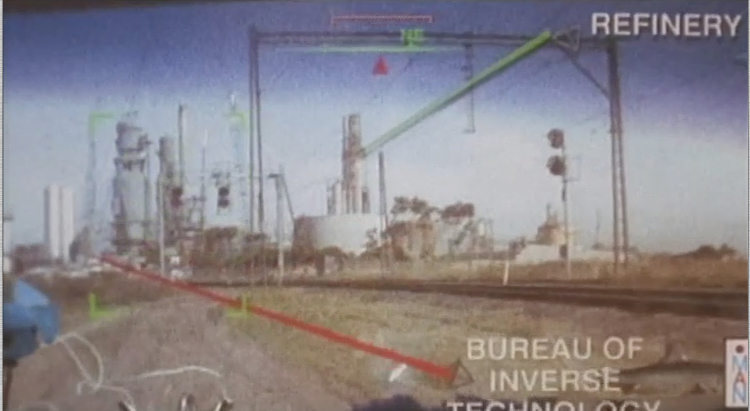

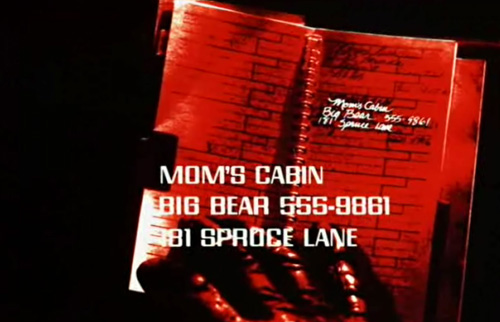

AR was probably first brought to most people’s attention via the Terminator and Robocop movies of the 1980s and 1990s. The robot machine-vision that superimposes text and graphics over a view of the real world from then on became synonymous with the viewpoint and “personality” of the cyborg.Most portable game devices today come with a camera built-in. Devices like the 3DS and the Sony PS Vita provide owners with AR content in the form of cards which when scanned present 3D or 2D content to the user. This content appears to float between the device and the card that is read by it. The content can be animated and can even appear to interact with the world around it, and the user can add content to it. For example virtual pets can appear to dance, respond to the hand of the user, and so on in a playful simulation of the real thing.

- The view through the sunglasses in They Live—A political form of Augmented Reality revealing the true ideological basis of capitalism and its advertising.

Data that is provided in real time by services can be viewed using AR, such as flight paths and flight numbers of commercial aircraft in the airspace around us. These often show the heading, bearing, takeoff, and estimated landing time of planes in the air. There are planet- and star-system based AR applications. These let the wearer/user view the heavens, not just as they appear now, but millions of years ago, and millions of years hence. In enabling the presentation of multiple time-frames simultaneously, AR technologies have been dubbed “atemporal” by Bruce Sterling. Sterling’s regular attendance and keynotes at the Augmented World Expo (AWE) conferences ensure a science fiction/literature/critical dimension to an event largely dominated by trade and business, and refocuses it upon art and technology.

In the final analysis, the convergence of AR with wearable computers, giving wearers an immersive experience and the power to intervene in and add to the augmented experience is still very new in terms of the lay person. The contribution of Steve Mann to the history of wearables and the event of Space Glasses today is to think outside the box and non-proprietarily about the entire idea of wearable computing. Mann’s explorations into the use of the eyeball itself as a screen upon which images are projected (as mentioned earlier), operating thus as a kind of “veil” of images over vision, closes the gap—even further—between the anatomical and the technologized body. His Eyetap headset, worn by him prosthetically as part of his developing research for several decades, utilizes the eyeball in this way. The wearer’s nervous and optical system are as nearly close to the electronic impulses—the flickering signifiers—of electronic networks as possible, suggesting an interrelationship and influence of one to another as a form of consciousness. This computer enabled, networked “seeing” self, moving within today’s wireless, wearable reality, experiences the new social relations of a now mobile human-machine. This subject will one day connect to the “Internet of Things,” making possible the completely mobile-networked “self” of the wireless city.

- Diorama stackable VRML Augmented Reality objects designed by David Cox, RMIT Masters’ candidate, 1998

At the MIT Media Lab in 1998, using 3DS Max, I (David Cox) designed a series of VRML floating augmented reality floating 3D “Signs” which were designed to “stack” and work in combination with each other. The objects would appear “unsolid’ when moving (such as when the user was panning) and “solid’ when not moving. Objects included a windmill (that rotated fast & slow depending on the level of bandwidth flowing through the room), an email mailbox, a navigational compass, a globe, etc.These were tested using a laptop and Silicon Graphics (SGI) based system called DIORAMA developed by Karrie Karahalios of the Social Media Group. For more information on this visit: http://fog.ccsf.edu/~dcox/EMU/EMUFRAMESET.htm

Wearable computers and Augmented Reality offer ways to further examine the complex inter-relationship between real and virtual space. These technologies to a large extent invert the paradigm of representing space on a flat screen, instead enabling information appear to permeate and interact with physical space itself. The area of wearable computers ties in with this broad theme, as these customized, small, portable, and “always-on” computers enable the user to fully engage with the space around them, annotating that space with information pertinent to it, and while doing so, communicate with other “Cyborgs” (as wearable computing aficionados refer to themselves) via wireless local area network cards.

There are inter-related themes which emerge when considering the possibilities of augmented reality—these have to do with the role played by media where digital content can be dynamic, reflecting changing aspects of the environment, or one’s relationship to it.

Given that dynamic information pertinent to a specific geo-spatial location can be made available to users of wearable computers, the role of this information resembles that of conventional fixed signage (ads, traffic signs, billboards, etc.)

SIGNAGE—symbols for navigation, information and instruction while online and moving through urban environments

MIGRATION—the constant moving from one place to another by the user of a wearable computer means that the act of moving itself can be the basis for certain types of digital media which are dynamic. An example is the windmill which slows down and speeds up depending on the rate of data traffic in Karrie Karahalios’ Diorama project. Although not a wearable computing project, this application was an example of basic augmented reality.

SPACE—that geospatial area occupied by the user as s/he undertakes daily tasks while using the wearable computer. Terrain traversed, land covered, urban space negotiated. There are several types of space which augmented reality gives rise to, that of i) the information, that of ii) the environment, and a third type of space which is the iii) conceptual intersection of the physical, the informational, and how they work together in the mind of the user.

DYNAMIC MEDIA—media which update, refresh, and present themselves in the context of constantly shifting environmental conditions, e.g., a directional sign which constantly points to the waypoint desired.

Otherzone

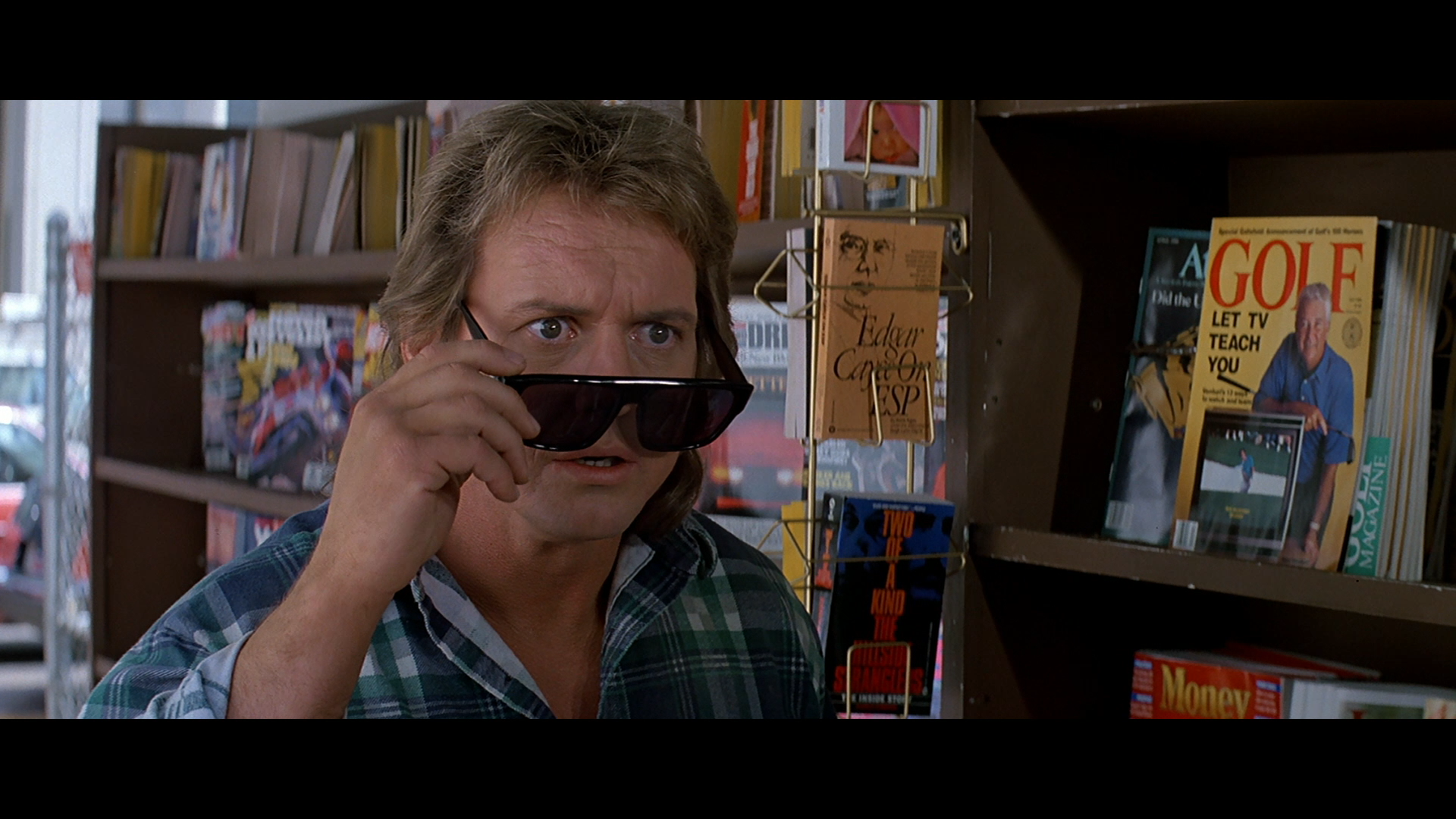

My 1998 film Otherzone enabled me to visually speculate on what augmented reality and wearable computers might look like several years from now. The media lab researchers had shown me what could be done with the (then) contemporary technology of shoebox-sized wearables and oversized head-mounted displays. It was not difficult to imagine in a few years the wearable computer disappearing into the structure of the display itself. The effect would be that of a pair of intelligent sunglasses connected permanently to the ‘net—hence “Netspex.” This has come true with technologies such as Google Glass and Space Glasses.

.

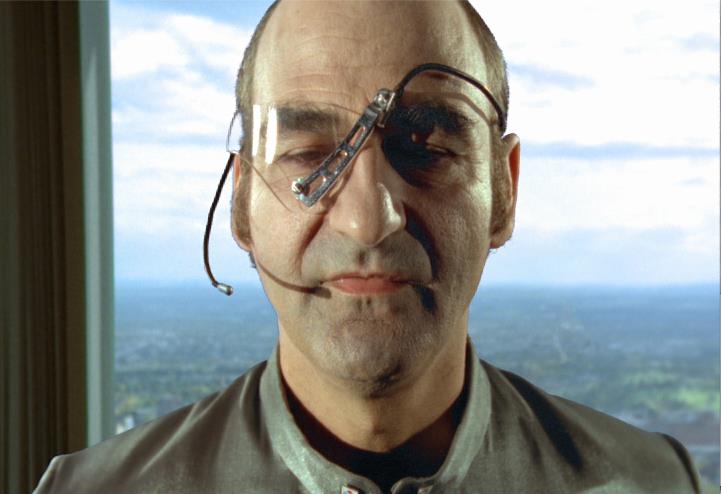

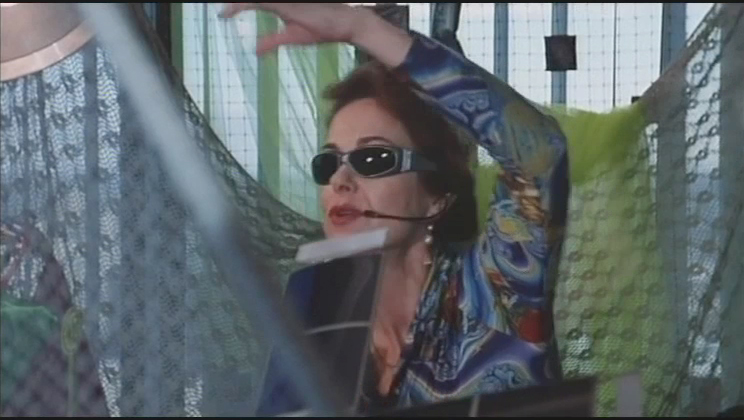

Otherzone’s “Netspex,” like today’s self-contained wearable computers, enabled the wearer to see and hear full multimedia as they move through urban space. In the case of the film’s villain, the Nam Melogue (played by performance artist Stelarc) has a monocular version of Netspex which enables him to instantly view any camera in the city. The heroine’s Netspex let her view videomail messages, and show her waypoints in the surrounding environment.

- My film Otherzone 1998—The Nam Melogue’s AR monocle let him access any camera in the city —total surveillance.

- Netspex as used in my film Otherzone(1998) for navigation and locating waypoints in the environment, customized to the user’s interest and needs.

Wearable Computers

I was first introduced to the area of wearable computers when I visited the MIT Media Lab in Boston in 1995. This visit was by invitation of the late Mr. William J. Mitchell (then Dean of Architecture and Urban Planning at MIT) who had visited Melbourne and RMIT that year promoting his book City of Bits.

I met Steven Mann and Thad Starner on this visit at the Software Agents Group section of the Media Lab. Both Mr. Mann and Mr. Starner had developed different approaches to the idea of wearing the computer on the body.

Wearable computers in the 1990s were small computers that drew power from rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Wearables enable the delivery of real-time information usually via head-mounted displays (HUDs) which the wearer uses for data delivery instead of a monitor. Input to the computer is provided by a range of means, either via sensors on board the device itself, such as infrared scanners, cameras, or other sensors, user input such as voice commands, keyboard input, or hand- or body-gesture input.

Wearable computer users are not immersed in a virtual reality, rather information augments the world around them, and information appears superimposed over the real world.

Wearable computers and Augmented Reality offer ways to further examine the complex inter-relationship between real and virtual space. These technologies to a large extent invert the paradigm of representing space on a flat screen, instead enabling information appear to permeate and interact with physical space itself.

Head-Mounted Displays (HDMs)

Head-mounted displays (or HMDs) enable the user of a computer to see the information on that computer as an overlay superimposed over the view of the world around them. With tracking software it is possible to have the data “placed” over areas of the room, or the broader environment. There are various ways that data can be placed—GPS data can be used, or in some cases, infrared scanning can be done using a device like the “leap motion” system that scans the room with very fine resolution “painting” process which then relays to the worn computer where objects should appear via the HMD. The computer user can manipulate objects using gesture control as if they were physical things, as is done in my film Otherzone where Kareen Hedding is shown moving objects like AR keys and locks and piggy banks around using her Netspex. In the film she is a proto Snowden, downloading information that will expose the truth behind her powerful employer, the Machines All Nations Corporation, the last tech company left on earth.

The Leap Motion system works in a similar way to the motion tracking used by Microsoft’s “Kinect” games controller that turns body motion into a means to manipulate game characters.

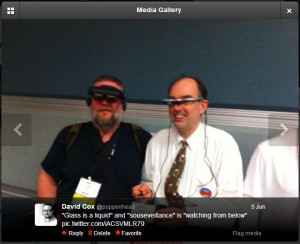

A pioneer in the development of head-mounted displays and wearable computers is Professor Steve Mann of the University of Toronto. Since the late 1970s Prof. Mann has been developing wearable computers and head-mounted displays. His earliest one comprised a crash helmet with a camcorder viewfinder taped to it, and radio antennae mounted to the top. It “talked” to the computer via radio waves. Later models involved having the image reflect off a mirror into a single eye, and this innovation culminated in the patented notion of “Eyetap,” in which the eye itself acts as both the camera and part of the display projector system. Mann now tours with his collection of head-mounted displays or HMDs to conferences, where his contribution to the evolution of the technology is undisputed. Mann is also a great champion of the principle that AR and wearable computers should be used to advance personal liberty and to facilitate what he calls souseveillance—“seeing from below.” as opposed to “seeing from above,” or surveillance.Mann has joined the META AR (which has since changed its name to Spaceglasses) team which has developed a competitor to Google Glass via Kickstarter, using Epson HMD and Leap Motion 3D tracking.

SPACEGLASSES offers true AR in that the graphics are true 3D, and 3D graphics creation is part of the long term idea of the project. The use of 3D tracking (similar to the Kinect system) means that hand gestures can be used for manipulating objects that appear in the field of view as in films like Iron Man and Otherzone.

Dynamism and Flow

There are inter-related themes which emerge when considering the possibilities of augmented reality—these have to do with the role played by media where digital content can be dynamic, reflecting changing aspects of the environment, or one’s relationship to it. Given that dynamic information pertinent to a specific geo-spatial location can be made available to users of wearable computers, the role of this information resembles that of conventional fixed signage (ads, traffic signs, billboards etc.)—signage and symbols for navigation, information, and instruction while online and moving through urban environments.

MIGRATION— the constant moving from one place to another by the user of a wearable computer means that the act of moving itself can be the basis for certain types of digital media which are dynamic.

Many contemporary films and videogames show scientists and specialists manipulating data in 3D as holographic fields of information. Floating, glowing holograms of the solar system, say as in Prometheus. The terrains of Pandora in Avatar, displayed for military and scientist alike. The head-up display is a product of the military fighter cockpit, and is installed in many recent model cars and passenger aircraft such as the Boeing 787. It combines the real world with information about that world simultaneously.

AR and Privacy Augmented reality apps abound for the tsunami of Chinese-made touchscreen devices; sensor-studded, Wi-Fi enabled, the modern data user is attuned to her environment much like a pilot, or a sci-fi movie or game character. After thirty years of AR in pop culture, from RoboCop to Terminator to Halo, to the windows-within-windows of every GUI you ever used, people are attuned today more than ever to superimpose data over their field of view.

Google Glass—The Mainstreaming of AR

In 2014 the Google Glass AR wearable system will go on sale. Glass is a head-mounted wearable computer with a built-in, see-through display and a 720 X 420 video camera & microphone. The tech lead on the project was Thad Starner, whom I worked with at the MIT Media Lab in 1998 when I was also working with Karrie Karahalios on the DIOMARA project.

Glass has has Wi-Fi, GPS, but the system is not strictly Augmented Reality. Google Glass is better described as “Annotated Reality” in that what you see are pop-up notes about what is going on around you, rather than objects and items that supplant or appear to stand in for real objects. Also the Google system is closed—it can only work with Google’s own proprietary search engine and other tools related to its artificial intelligence-like data-gathering system. Glass bears a striking similarity to Steve Mann’s “eyetap” system from 1999, particularly the concept of the display being reflected in a 45% prism to enable the eye to see directly through it.

In his keynote address at the Augmented World Expo this year, Mann discussed the similarities onstage:

In the talk Mann makes a point which begs the question of meaningful AR—”‘if glass cannot help you see better, what good is it?”—I interpret this as a direct challenge to Google Glass. Far from helping individuals “see” at all, on the contrary, Google Glass obscures their view with advertising-driven annotations that serve to simply bring obtrusive social media content physically closer to a user who now does not have to stop all other activity to perform them with a smart device with a touchscreen. True AR seeks to augment not just vision, but the entirety of experience itself. Reality itself. True AR is a form of electronically-mediated Situationism.

DIY Wearable Computers

With partner Molly Hankwitz (together we form Archimedia), I built a wearable computer using a raspberry Pi computer and my old Virtua-IO glasses from the late 1990s that works fine for most basic computing needs but it has been field-tested for Situationist-style drifting. Notes are taken using it while walking through urban areas.

- Archimedia’s Raspberry Pi based wearable computer ,the “Debord.” Total cost, about $200. Designed to enable the user in her drifts around the city. When Bruce Sterling saw it, he took a picture. CC Archimedia 2013

There are more DIY wearable computing solutions on offer, and at the low-end the humble Raspberry Pi represents a keen entry-level $35 very portable computer for those wanting to build a low-cost computer to carry around. As for head-mounted displays, these are bound to become cheaper as time goes on, but the META system, now named SPACEGLASSES, which is based on an EPSON head-mounted display, is the sort of rig that most people can afford, costing several hundred dollars. Not so with Google Glass, which sells for up to $1,500 a set. No doubt in several years, as with Walkmans, MP3 players, and other consumer electronics devices that started out closed, expensive and a high-end fashion item, prices will fall and the innovation can really start to take place.

Controversy has always surrounded wearable computers. In general terms these revolve around the conflict between on the one hand the empiricist argument that the devices are part of uniforms, and extensions of institutional power and authority. The user is not supposed to know how they work, only that they work. The alternative view is that the devices are customizable, individualized, made to suit the specific needs of the user, who then connects with others of like mind and technical sensibility to form collectives. In the mid-1990s these conflicts played themselves out in most hubs of power, wherever large contracts were to be argued over. As in the film Brainstorm, the Pentagon and the government had its own notion of wearable computing should be for—a device of uniform specification, issued to a mass, whose use of it would render the content that of an aggregate. This is the model used for Google Glass, which is a more efficient way to suck up personal videos, emails, etc. by a population who neither knows nor cares how its data is used. The other model is a customizable system that can be made to adapt to the needs of a user base who decides for itself not only how the devices are used, but how the data generated by the devices is to be used.

Steve Mann has dedicated his career to the principle of personal technology as “an architecture of one.” Mann believes that wearable computing and augmented reality should be a force for good in the world, a force for social justice and a force to benefit society. Not for profit alone. Not for surveillance. Not for military and control. Not for policing. Not to better further the narrow interests of property, ownership, and privatization.

Inspired by the examples of Mann & Starner, I built my own wearable computer in 1997 in Melbourne using a macintosh Duo laptop with a broken screen. I had joined the wearhard-haven mailing list based at the MIT Media Lab and started by the wearables team. Then as now, battery power is the biggest stumbling block to ongoing wearables activity, but the possibilities of “always on” media access have always been a source of fascination.

- David Cox with wearable computer made from Macintosh Duo laptop, Melbourne, 1997, copyright David Cox

It is thus incumbent upon us all to develop the new technologies with a mind to the great power of the innovations they imply and above all else, the important social relations they are sure to bring forth.

Picture I took of Steve Mann at the MIT Media Lab when I interviewed him in 1996. Copyright David Cox.

Myself (without wearable) with Steve Mann when I interviewed him at the AWE2013 Conference, Santa Clara. Copyright David Cox.

Myself with Steve Mann (both with wearables), from my Twitter feed, at the AWE2013 Conference, Santa Clara. Copyright David Cox.

- Meta AR (AKA SpaceGlasses)—a true AR developer kit that enables hands-on customization and unlike Google Glass, true AR, not simply annotation of information over your view of the world.

- Plus it has Steve Mann onboard, which means that it has some theoretical chops behind it is probably not only driven by advertising and profit but a genuine interest in the potential social and cultural potential of the medium.

Link Resources:

Steve Mann personal website: http://wearcam.org/steve.htm

David Cox Research Page: http://fog.ccsf.edu/~dcox/EMU/EMUFRAMESET.htm

Spaceglasses (formerly Meta AR): http://www.spaceglasses.com

META AR successful Kickstarter campaign: http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/551975293/meta-the-most-advanced-augmented-reality-interface

META AR renamed “SPACE GLASSES” PROMO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7I7JuQXttw#at=55

Game Draw on Meta: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iWPdAhhUWD0#at=12

AR and ART: http://owni.eu/2011/05/23/augmented-reality-the-boundaries-of-invisible-worlds/

Technopanic: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/14/google-glass-ban-privacy-concerns_n_2856385.htmlhttp://technorati.com/social-media/article/google-glass-banned-in-a-bar/http://www.forbes.com/sites/daviddisalvo/2013/03/10/the-ban-on-google-glass-begins-and-they-arent-even-available-yet/

Augmented (hyper)Reality: Domestic Robocop http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fSfKlCmYcLchttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AFiE82Npbn4

AR in Cars http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mWISF_KzP0w

FROM WAGNER TO VR http://www.w2vr.com/Teachers.html

AUGMENTED REALITY

Augmented Reality Through Wearable Computing http://www.cc.gatech.edu/~thad/p/journal/augmented-reality-through-wearable-computing.pdf

Thad Starner http://www.cc.gatech.edu/~thad/p/journal/using-gps-to-learn-significant-locations.pdf

Wearable Computers http://www.interaction-design.org/encyclopedia/wearable_computing.html

Steve Mann Keynote, AWE2013 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhVdTFcR6TA

Bruce Sterling Keynote, AWE2013: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ohatuq8tekk

Will Wright Keynote, AWE2013: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4d0k_7pdPGg

AR & CINEMAhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6c1STmvNJc

Steve Mann Interviewhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oG0COnQk_CA

Pranav Mistry: The thrilling potential of SixthSense technologyhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YrtANPtnhyg

I love what you are doing in the way of democratizing wearable technologies in even making potential uses known to the readers of OC! I often worry about the possibilities for distribution, and thus efficacy by numbers, of subversive/artistic implementations of wearable technologies. However, I’m hopeful that open-sourced interfaces (and therefore their purposes and functions) will provide alternatives to otherwise technologically “determinist” conceptions of the economical and social future for wearable computers and AR as familiarity with the interfaces expands, which can of course only be done through steady and critical dialogue. Thanks Archimedia!