Interview with Jack Sargeant

by Ed Halter

(Click here for printer-friendly version)

This interview was conducted in fall 1999 for the release of Jack Sargeant's CINEMA CONTRA CINEMA. We met in the shabby bar in the lobby of the Gramercy Hotel and spoke over drinks. Unfortunately, my editor at the NY PRESS passed on the article, and this chat languished until OTHERZINE editor Noel Lawrence demanded that it rise from the dead and find a new home here. - EH

EH: How'd you come across American underground film? Was it readily available in the UK when you started writing about it?

JS:

In like 1985, I was 17 or 16 and I

had already been reading Burroughs'

books, reading underground literature

and listening to underground music

and stuff since I was like 12. I was

really precocious. I was involved

in putting on bands and at one time

we flew over Lydia Lunch and she brought

[Richard Kern's film] The Right Side

of my Brain and we screened that.

I was really intrigued by it. It had

the same kind of attitudes as underground

literature and music but it was visual

and that was something I was really

interested in. I already knew a lot

about video art and stuff like that,

structuralist video art in England

from the 70s and 80s. [Kernıs film]

really made me interested in stuff

that was beyond that kind of structuralist

video art nonsense. I guess the other

way into it was in England in '84...

You know, in the early 80ıs, the English

more than anywhere else bought technology.

Like everyone in England has had mobile

phones for years and such. Everyone

in England in the early 80s had a

videorecorder, really fast. They were

massive. And you could get any kind

of sleazy movie then. It was like

having old-style 42nd Street down

at your corner shop. So you could

go in and get Snuff, Texas Chainsaw

Massaccre, SS Experimentation Camp,

all these incredibly violent movies.

JS:

In like 1985, I was 17 or 16 and I

had already been reading Burroughs'

books, reading underground literature

and listening to underground music

and stuff since I was like 12. I was

really precocious. I was involved

in putting on bands and at one time

we flew over Lydia Lunch and she brought

[Richard Kern's film] The Right Side

of my Brain and we screened that.

I was really intrigued by it. It had

the same kind of attitudes as underground

literature and music but it was visual

and that was something I was really

interested in. I already knew a lot

about video art and stuff like that,

structuralist video art in England

from the 70s and 80s. [Kernıs film]

really made me interested in stuff

that was beyond that kind of structuralist

video art nonsense. I guess the other

way into it was in England in '84...

You know, in the early 80ıs, the English

more than anywhere else bought technology.

Like everyone in England has had mobile

phones for years and such. Everyone

in England in the early 80s had a

videorecorder, really fast. They were

massive. And you could get any kind

of sleazy movie then. It was like

having old-style 42nd Street down

at your corner shop. So you could

go in and get Snuff, Texas Chainsaw

Massaccre, SS Experimentation Camp,

all these incredibly violent movies.

EH: Were these movies never theatrically released in Britain?

JS: Not really.

EH: I remember some of the London Exploding Cinema people telling me that Corman films were just getting popular recently because they were never really available there.

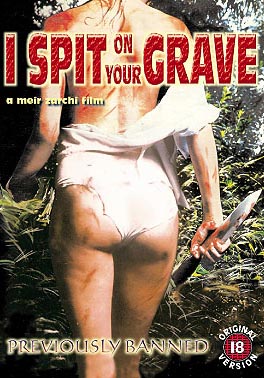

JS: Well maybe some of the Cormans

were. But in England there's really

strict cinema censorship, so when

these films started appearing on video

people were really excited. There

was an explosion when  ordinary

people were renting the most insanely

violent movies like I Spit on Your

Grave. And then in '84 I think it

was, the Government passed a Video

Recording Bill where they could actually

censor videos the way they censor

films. So immediately a lot of that

stuff was banned. I was the kid at

college, like at 16 years old, who

had access to all these sleazy horrible

movies. I knew people who collected

horror movies. I'd go to these friends

places and pick up copies of Morpheus

the Beast, horror movies and sleazy

movies, stupid movies like that. We'd

just sit around getting fucked up

and watching these stupid movies for

hour after hour after hour. I was

always the person who had the contacts

to get ahold of this stuff. So when

I started seeing these underground

films, by putting on shows and stuff,

it was just a natural thing that you'd

ask the people you got your video

nasties from, "Hey, have you heard

of this film." You know you kind of

followed these rungs into that space.

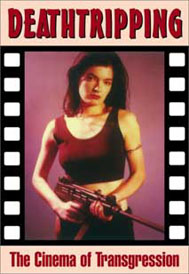

But it wasnıt until I was writing

DEATHTRIPPING that I got to see...I

think I saw Flaming Creatures when

I was writing. DEATHTRIPPING, that

was the first time I'd seen it. I

had seen a lot of the obvious stuff,

like Tony Conrad, but that kind of

New York gay stuff I didnıt see until

I was 23 or 24, when I was writing

DEATHTRIPPING. I had seen some of

the European underground stuff like

Genet's Un Chant D'Amour, and I had

seen the Kuchars because their films

are kind of well known in England.

Mark Finch released it there. So yeah,

I had this kind of odd, piecemeal

education in underground film, which

I guess everyone has because you can't

just sit down and watch underground

film all that easily. Even at the

Anthology Film Archives, there's certain

things they'll show and certain things

they won't. It's not like you can

just go out and see anything. It's

not like where you just walk into

your corner bodega and hire any film-noir

or horror movie and educate yourself

fairly easily.

ordinary

people were renting the most insanely

violent movies like I Spit on Your

Grave. And then in '84 I think it

was, the Government passed a Video

Recording Bill where they could actually

censor videos the way they censor

films. So immediately a lot of that

stuff was banned. I was the kid at

college, like at 16 years old, who

had access to all these sleazy horrible

movies. I knew people who collected

horror movies. I'd go to these friends

places and pick up copies of Morpheus

the Beast, horror movies and sleazy

movies, stupid movies like that. We'd

just sit around getting fucked up

and watching these stupid movies for

hour after hour after hour. I was

always the person who had the contacts

to get ahold of this stuff. So when

I started seeing these underground

films, by putting on shows and stuff,

it was just a natural thing that you'd

ask the people you got your video

nasties from, "Hey, have you heard

of this film." You know you kind of

followed these rungs into that space.

But it wasnıt until I was writing

DEATHTRIPPING that I got to see...I

think I saw Flaming Creatures when

I was writing. DEATHTRIPPING, that

was the first time I'd seen it. I

had seen a lot of the obvious stuff,

like Tony Conrad, but that kind of

New York gay stuff I didnıt see until

I was 23 or 24, when I was writing

DEATHTRIPPING. I had seen some of

the European underground stuff like

Genet's Un Chant D'Amour, and I had

seen the Kuchars because their films

are kind of well known in England.

Mark Finch released it there. So yeah,

I had this kind of odd, piecemeal

education in underground film, which

I guess everyone has because you can't

just sit down and watch underground

film all that easily. Even at the

Anthology Film Archives, there's certain

things they'll show and certain things

they won't. It's not like you can

just go out and see anything. It's

not like where you just walk into

your corner bodega and hire any film-noir

or horror movie and educate yourself

fairly easily.

EH: Yeah, I remember Jonas writing somewhere that at one point he knew every independent filmmaker in the US personally. Now even people who specialize in underground film can't possibly see everything. I mean you might hear of it, but its just not feasible to see everything. So you began with the 70s and 80s Cinema of Transgression with Deathtripping, then you wrote about mostly 60s Beat cinema in NAKED LENS. Then this new collection, CINEMA CONTRA CINEMA, covers mostly 90s underground cinema. What kind of differences do you see in contemporary work? What kind of comparisons come to mind, compared to these older traditions?

JS: The first thing I notice about the modern stuff, is that people are far more willing to talk to each other and cross divides. There isn't a single style. People are willing to talk to communities they don't necessarily have anything in common with. For example a filmmaker like Mark Hejnar from Chicago, who makes these kind of post-industrial, fast edits, burning pig's heads and naked bodies and blood and noise-music stuff - he can sit down and have a beer with Jim Sikora who makes these long, serious, post-Jim Jarmusch narrative features. And they'll all sit down with Tyler Hubby who makes films where nothing happens for 22 minutes. It's not like everyone's saying oh we're this or we're that, defining themselves. People willingly sit and talk, even though they might hate each others work or not understand each others work. Which I find quite interesting. Because especially in the Cinema of Transgression stuff, particularly in the way it's presented in Zedd's Manifesto, it's very much us-against-everyone else. Although that's not true, that's the way its presented. And then with the Beat stuff - well, in a way that's kind of a fake book, because it's like basically I created a genre. It's not like people sat down and said, "We're Beat filmmakers." It was just a way to market a book about filmmakers who used the same ideas as Beat literature. Certainly Antony Balch, for example, dosen't have anything in common with Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie. Robert Frank and Alfred Leslie's film is very much about poetry and jazz, whereas Antony Balch's movies are just about as much fun as being hit in the face. Which is kind of the point. They're very much into that Burroughs thing. So I guess the modern stuff was interesting in that people are very social. There's this feeling that we're all in it together. People's tastes are different, so for example at the NY Underground Film Festival, there's all kinds of people just hanging out, and no one really cares if they like each others' work, theyıll still go sit and talk about it over beer or coffee or whatever.

EH: And Nick Zedd sees everything, and is really into a lot of it.

JS: Yeah of course, although he insists in print that he hates everything.

EH:

Another big difference is that these

two earlier books are largely based

around New York City, whereas in CINEMA

CONTRA CINEMA, the filmmakers are

from all around the US, and even a

few from Britain. The movement is

much more spread out now, itıs not

like in the old days with just a bunch

of New York friends defining what

goes on.

EH:

Another big difference is that these

two earlier books are largely based

around New York City, whereas in CINEMA

CONTRA CINEMA, the filmmakers are

from all around the US, and even a

few from Britain. The movement is

much more spread out now, itıs not

like in the old days with just a bunch

of New York friends defining what

goes on.

JS: Yeah, there's a lot of stuff happening on the West Coast. A lot of it really irritates me, because Iım not really interested in political filmmaking.

EH: Who's stuff do you mean? Like Craig Baldwinıs?

JS: No, I really like Craig Baldwin. I mean, I can't even name names of the stuff that irritates me, because I just blank it out. But yeah, there are really a lot of good people all around. People like Danny Plotnick, who's just incredible, or Craig Baldwin, who's good, on the West Coast. But New York for me...well...I always liked this idea that Warhol and his friends took lots of speed and stayed up for days on end listening to the Velvet Underground, you know, really repetitive noise music, and watching these movies about their real lives. Or kind of camp version of their real lives. And on the West Coast, you had people taking lots of acid and watching color flashing films. I guess the New York stuff I always like cos I like the idea of staying up for hours, wearing all black and watching miserable depressing, slightly camp films far more than I like the idea of watching flashing colors and hugging people. That's my personal thing.

EH:

One of the things about your books

that stands out is that youıre informed

by academic theory. In NAKED LENS,

there's a part where you mention "queer

theory" to Allen Ginsberg, and he

almost bites your head off. Do you

have any other kind of...

EH:

One of the things about your books

that stands out is that youıre informed

by academic theory. In NAKED LENS,

there's a part where you mention "queer

theory" to Allen Ginsberg, and he

almost bites your head off. Do you

have any other kind of...

JS: He was really cantankerous! I mean, he died like two months after that so at that time everything about him was cancerous.

EH: But describing Huck Botko's work in terms of Lacan, for example - do you find that filmmakers react well to this? Knowing them myself, they are a cantankerous bunch, who don't really like the uh...

JS: Well, you know a lot of them are university-educated but in denial! I got this one really bad review of one of my books I did, this book called Suture, and they said I had this "agenda." That I didn't just say what the work is. But it would be so boring to sit and read a book with like, "this film opens like this and then it happens and then it ends." Of course I've got an agenda. I've got ideas I think about and films I like. For me, what would be really good would be if someone wrote about the same filmmakers and said I was totally wrong and said, no this is what they're about. Cos I mean what's interesting about any art is that it inspires you to think. It inspires some kind of discourse. It's not about worshipping filmmakers as auteurs or something. Because some of these filmmakers, they genuinely don't know why their films are good. Then some of these people are really engaged in critical questions. Someone like Tessa Hughes-Freeland makes films that totally understand these questions of voyeurism, the process of watching films and scopophilia and so on. And using found footage, the way in which you can construct a film from found footage and re-address the way that people watch the film. Then you get other people who...well, Huck Botko's a good example of someone who deliberately denies any academic or theorical pretentions. But then my whole point of view is that the thing he's attacking again and again is the family, and at some point you have to read that in terms of psychoanalytic ideas of the family, and social ideas of the family as this kind of conditioning space you grow up in. It's incredibly taboo to say "Fuck yer Mum" or whatever. I mean not literally doing it but saying it, and that's the kind of anger he has in his films. It's certainly taboo, and just to say he makes these films where he feeds bad food to his parents, it's just an understatement to the power of what he's doing, because he's challenging the roots of society in that way. So you have to look at it from a degree of academic perspective. I'm sure Huck's role is always to be against someone doing that to his films. Obviously, the outpouring of anger is a function of his films. And to sit down and analyze that outpouring of anger would for him be useless.

EH: Like analyzing a joke.

JS: Yeah. Exactly. I mean though, that's most of what I do, is analyze something. But really what I'm saying is why I like it and why I think it's important. It's not like I'm going in and saying "I've got to get this theory in there." Plus, the fact is, I really get bored with this idea that you should worship filmmakers like auteurs, or you should have this European Marxist idea that you should analyze films to death. Some films should be looked at a lot and some shouldn't be. I mean ... I always wanted to write just like Bataille. What can I say.

EH:

Well speaking of Bataille... the main

theoretical model that emerges throughout

all your books is the notion of transgression.

It's almost like you're looking at

the past and the present of underground

film through the lens of the Cinema

of Transgression. Why do you find

transgression to be so persistently

central to underground film?

EH:

Well speaking of Bataille... the main

theoretical model that emerges throughout

all your books is the notion of transgression.

It's almost like you're looking at

the past and the present of underground

film through the lens of the Cinema

of Transgression. Why do you find

transgression to be so persistently

central to underground film?

JS: Well, historically, all the major underground filmmakers were gay. And up until '68 in England or '69 here, it's therefore always linked to some kind of transgressive behavior, that people literally could get locked up for. There's also the fact that a lot of them had radical political beliefs. Which again, nowadays doesnıt seem like a big deal. But Jack Smith doing screenings of his films against prisons for Beatniks Against Prisons in '64, you know that's a big statement to make. And that's transgressive, especially in a culture like America, supposedly the pinnacle of capitalist culture. For someone like Jack Smith to be doing this, it's a big rule breaking gesture. Underground culture is always going to be challenging assumptions, breaking rules, and thatıs what's fascinating about it to me. It goes into social, political and psychological areas that most non-transgressive art doesnıt do. To look in those areas is also a transgressive gesture. We pretty much take for granted now that certain areas aren't forbidden. But I think that there are. It's like we were saying earlier about Fight Club. Itıs really easy to say, oh you know this film isn't all that good, because we've all seen Fingered. But if Joe Schmo who's18 years old, sitting in the middle of Buttwipe, Wisconsin, see's it at a mall, that's very different. So we itıs really easy to say anarchy, homosexuality or whatever isnıt that transgressive anymore. But it still is, to most of the people on the planet. There's this notion that transgression is a continuous process of testing the boundaries. I always have to return to David Wojnarowicz's idea that transgression is a kind of response to a social and political situation. That's what he says in Close to the Knives: "...and the walls came down during Reaganomics and all you could do is trace the boundaries and do the best to destroy them or yourself." There's this notion that you've *got* to do it. And that's something that I still see and I still think its really important. You have got to challenge things. The fact is that most people are just happy to go to Starbucks and drink homogenized coffee and go see Phantom Menace and consume passively their lifestyles. And to me there's nothing more boring than consuming passivity. This desire for homogeneity that people have now is just terrifying. They're looking the same and reading the same and watching the same movies and drinking the same coffee. It's so sad.

EH: It's getting worse in New York. It's what everyone here talks about.

JS: What, how good it is to be the same? Well it's the whole Guiliani thing...

EH: No, how New York itself is becoming more homogenized, with a Starbucks and a Gap on every corner. It feels like you're walking around in a mall sometimes.

JS: Well and the communties that are dissident of that are slowly being forced out.

EH: At least off of the island, yeah.

JS: Yeah out to Brooklyn and the Bronx and Staten Island and such.

EH: Well, Brooklyn benefits then.

JS: I think that's true yeah.

EH: You were saying that you have gotten criticism for the use of academic theory. Part of that response, I'd imagine, is the problem that there just aren't many people who write about underground film. So the onus falls on you. But there have been a few people over time, like there's been Parker Tyler, Gene Youngblood, Jonas Mekas. How has their work played into yours?

JS: It's all functional. I read it and use it and build on those ideas and so on, use their ideas and histories and so forth. It's not like I was a huge fan of their work. The only person I was a huge fan of was Jack Stevenson because, again it's like to some extent a youth thing. In my writing I was rebelling against previous generations. Like Nick Zedd rebelling against underground film. Obviously you can't rebel against it. But to some extent Jack Stevenson was one of the first writers I read that really articulated that stuff well. Actually now, I have read Film as a Subversive Art.

EH: Amos Vogel, yeah.

JS: Yeah, that's one of my favorite books now. But when I first started, it was stuff like Jack Stevenson that really had an impact on me. Of writers who are working now, I really like David Kerekes, although some of his stylistic methods are irritating, but that book he wrote about the history of snuff movies -

EH: Killing for Culture?

JS: Yeah, that one. It's a great book. It's wrong in a lot of ways, but no one else put that information together.

EH: To draw it together as a genre, I found that incredibly interesting.

JS: Yeah, so people like that. I guess they're my contemporaries in some way, although I'm the youngest of all of them.

EH: How old are you?

JS: I'm 31. I mean I started doing this stuff when I was in my early 20s.

EH: Were you in touch with people who were writing zines in the US about underground film at the time, like Steve Pulchalskiıs Shock Cinema?

JS: No. EH: So there was no US-UK interplay in terms of writers? Was Psychotronic available?

JS: I used to read all those magazines, but I never wrote to those people or communicated. I don't know why I didn't. It just didn't appeal to me. I have respect for what those people did, but I don't really like a lot of their writing. Again, it's like they were really good at getting their facts down, but they didnıt have anything more than that in the zines of the time. Though looking back at them now, they were hugely important. If you actually look at the original proposal I wrote for DEATHTRIPPING, I didn't want to write it. I said I would edit it and write one chapter. I had hoped other people would do it. I wanted to see someone else write about. But since no one else would do it, I had to do it! It was the same with all of them. If I wanted to find out about it, it's going to have to be me doing it.

EH: Just like a lot of these underground filmmakers.

JS: Yeah, exactly. If you want to see a girl tied up in 1980, in an art movie, you couldn't. So Richard [Kern] had to make his own wank movies. That's what he did. I'm sure he wouldn't say that.

EH: Well he probably wouldn't say "wank movie."

JS: He actually does say it, doesn't he, in "The Evil Cameraman." Where you've got that whole sort of joke about him as a sleazy filmmaker. It becomes a kind of joke.

EH: I've always thought that after gay rights and everything came around in the 80s, that perverted straight people are really the heir to the gay tradition, arenıt they?

JS: In a way thatıs true. In a lot of ways the gay community is pretty conservative, isn't it? It includes a lot of people, but to an extent it's quite conservative. Politically and stuff, gay people have 10 times as much money, they tend to be working and not have children and stuff. So their situation tends to be very different.

EH: Also in the cities now, and in the art community, gay people have been so successful in creating a zone for themselves that they can get away with anything and it's okay. Bruce La Bruce can show hardcore sex at a gay film festival. Whereas Ian Kerkhof's making the same kind of film with straight sex, and he's shut out completely, outside of the underground festivals. So I really do think that the next wave is straight perversion, cos that's still outside. No one's standing up for them, whereas to our benefit, gay people do stand up for our own, but no ones there to stand up for Kerkhof, or Kern.

JS: That's my job, to stand up for the straight perverts.

EH: So whatıs in the future now? Do you want to talk about what you're working on?

JS: I've got a new edition of DEATHTRIPPING

coming out in March. That's gonna

have all of the  updates

about what everyone's doing now, like

Tommy Turner's film The Magician,

all the Zedd stuff, Kern's photographs,

Tessa's new movies. And I've got this

book I've been editing, about the

history of the road movie. No one

had ever written a good book about

the road movie, and if there's any

mainstream genre that I think's really

interesting itıs the road movie. You

talk to everyone and their favorite

movies are road movies. You know,

They Live by Night, Natural Born Killers,

Badlands, whatever. You actually start

looking at Detour, The Getaway (the

Ali McGraw-Steve McQueen one), and

even down to movies that are crap

but highly entertaining, like Convoy,

and itıs a really big genre and no

one's really written about it. So

I've been editing this book about

the road movie. That road movie book's

due out Februrary-March time. And

Suture Two's gonna be out at the end

of next year. And there's gonna be

a lot of weird film in that, mostly

from Europe. I also write for Headpress

and Bizarre as well.

updates

about what everyone's doing now, like

Tommy Turner's film The Magician,

all the Zedd stuff, Kern's photographs,

Tessa's new movies. And I've got this

book I've been editing, about the

history of the road movie. No one

had ever written a good book about

the road movie, and if there's any

mainstream genre that I think's really

interesting itıs the road movie. You

talk to everyone and their favorite

movies are road movies. You know,

They Live by Night, Natural Born Killers,

Badlands, whatever. You actually start

looking at Detour, The Getaway (the

Ali McGraw-Steve McQueen one), and

even down to movies that are crap

but highly entertaining, like Convoy,

and itıs a really big genre and no

one's really written about it. So

I've been editing this book about

the road movie. That road movie book's

due out Februrary-March time. And

Suture Two's gonna be out at the end

of next year. And there's gonna be

a lot of weird film in that, mostly

from Europe. I also write for Headpress

and Bizarre as well.

EH: And for Fringecore, the magazine.

JS: Oh god yeah, I write for Fringecore as well. And somebody in England keeps trying to get me to do a book on English underground film, which I'm loathe to do.

EH: Why's that?

JS: Uh...

EH: Because I noticed, by the way, that the three Brits that you have covered - Jeff Keen and Peter Strickland [in CINEMA CONTRA CINEMA], and in the other book [NAKED LENS] you've got Peter Whitehead - theyıre all Brits who like American stuff, who are American-obsessed.

JS: I don't think Jeff Keen is - he's just a consumer of cinema. I dunno. The British underground film scene is really happening now and kind of really exciting, but it goes back to that East Coast-West Coast thing I mentioned earlier. I really like the idea of taking lots of speed and staying up all night listening to the Velvet Underground and watching people cut themselves up, rather than watching flashing colors. And the English underground has a tradition of like...well, I remember going to the Expoding Cinema once and they're having five films at once playing and DJing and stuff. To me, that's a part of that West Coast psychedelic thing.

EH: Part of rave culture.

JS: Yeah. I like miserable, depressing

cinema! I like camp and funny ones

too, I like the idea of watching late

at night at a bar somewhere, not going

to a hall full of hundreds of people

and watch 10 movies at once with a

DJ. I mean, I can enjoy that experience,

but it's not really me as a person.

Also I've been organizing the first-ever

official release of Cinema of Transgression

movies in England through the British

Film Institute. So I'd like to think

that Iıve destroyed them completely

by making them respectable. Which

I guess will piss Zedd off. Finally

respectible!