The Air We Breathe

11 Sep 2010

"GAMEPLAY" IS AN ELUSIVE term that describes what makes a successful game work. Gameplay is the result of a feedback loop between the game player, the player's physical input and the central processor of a computer and how it in turn interprets that input before sending it to the audiovisual display. Ernest Adams has described this loop as the key to understanding how a game engages the player.

Games generally entail an immersion in Huizinga's so-called 'magic circle'--a place consensually agreed upon as a site where rules that govern the outcome of a shared creative process can occur. The magic circle is any sports arena, any courtroom, any classroom, any place where there are rules in place that are commonly understood by those that are there. Video-games lock us in a magic circle also, as do other forms of simulated experience (such as motion pictures).

At MIT in 1961 the Tech Model Railroad Club were obsessed with sci-fi writer E.E. "Doc" Smith, particularly the 'Lensman' novels which featured massive spaceship battles. With the arrival at MIT in 1961 of the powerful Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-1 computer, the group built one of the first true videogames: 'Space War.'

'Space War' involved two armed space craft--called "the needle" and "the wedge"--attempting to shoot one another while maneuvering in the gravity pull of a star. The ships fired missiles at each other. Each ship had a limited number of missiles and a limited supply of fuel.

The elaborate train sets the group had built worked using recycled telephone switchboard relays and solenoid switches. Model-building has in common with games an appeal to the aesthetic of wanting to vicariously control the movement of something in a parallel world, to see an object-that-is-you (your avatar) move as you would yourself like to move. Such movement is free of constraint by virtue of some hidden but effective and predictable mechanism--some governing switch system, all right in front of you, which you are able to witness while also experiencing the joy of managing the flow and dynamics of objects in space.

Spacewar for the PDP-1 computer circa 1961.

Doug Englebart at Stanford in 1966 was also something of a gamer. He imagined computer space as something navigable. He moved the primitive wooden-clad mouse and used a headset to show the world that computers were places to inhabit and play in. The classic video of his demo is the stuff of legend and his delivery is full of the pride and wonder we associate with those truly moved by the implications of what they discover. Here was a vision well ahead of its time in which the use of computers was a thing of joy, full of the thrill of being in control of a space which augmented the imagination and set free the possibilities of thinking itself.

I am a writer who has played videogames since their arrival to ordinary places (not university departments) in the mid 1970s. I was rather young then, a child really, but I was old enough to fathom the significance of the arrival of these first computer game cabinets in the streets, lives, and experiences of those around me.

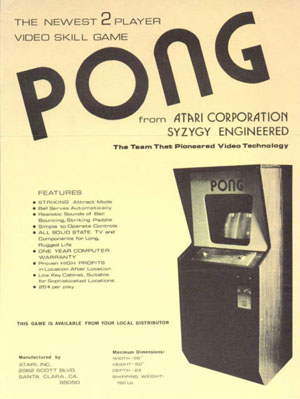

The first videogame I ever played was 'Pong,' in 1975. The occasion was a fish 'n chip shop run by a middle-aged Greek man called Con, who sold 'minimum chips' (sauce 2cents extra) to the local kids in what was then a working class, former holiday-resort-area, of Melbourne called St Kilda.

Google street view showing where I played my first videogame. I lived on the street to the right.

The store was on the corner of Carlisle and Barkly streets and is still there. The cabinet made the machine look as though someone had decided to encase a TV. My first impression was that this was a television for customers. I had no other context by which to judge why a TV monitor would be in a take-away food joint. Where were the dots coming from, what was this knob for?

"Avoid missing ball for high score" read the instructions. Words, as I would later understand, to live by.

'Pong,' the first commercially successful videogame.

When we speak of the user interface being the key point of entry to a videogame's world, we don't necessarily mean simply the physical buttons and knobs and joysticks that are mounted on the cabinet. Rather we mean the whole entirety of the game as it exists--in situ--on the street, out there in the public space where people can walk up to it and use it. The interface includes the venue, the location of the venue in the city, and the role that venue (and the machines within it) plays for those that make use of the venue. An arcade in the mid 1970's was a place you actively went looking for--a place to congregate away from the eyes of parents, teachers, and other authority figures. As a refuge from the scrutiny of those who might cramp one's style, the arcade naturally attracted those with a vested interest in keeping a low profile. Like dives, strip clubs, speakeasies and porn theatres, pinball arcades in the 1970's were the last dying embers of that vaudeville culture that had ushered in cinema, the penny arcade, the freak show, and the carnival. Soon they would die out altogether, in the wake of the arrival of the videocassette recorder, the gradual homogenization of retail culture (through malling and theme-ing), and the erosion of the culture that underwrote their steady patronage (working class youth). Manufacturing and the sensibilities that accompanied it, by the mid 1980's, were soon to be replaced by service industries and the steady rise of what we now look back on as the information economy.

The area of Melbourne in which I lived, St. Kilda, had in the first two decades of the 20th century been an antipodean answer to England's Brighton and New York's Coney Island; it was a retreat for the middle classes to a beach area where morals could be loosened slightly and recreation could interrupt an otherwise dreary working life between weekends. Early '70s St. Kilda was sleazy and run-down, but the distant hint of flappers in bathing suits and the "carny" barker were still in evidence in the peeling paint and fading images of the last remaining entertainment edifices from the 1920's.

The one-block sized theme park, Luna Park, dominated the area, with a roller coaster built by the same intrepid crew that had constructed the one at Coney Island (all wooden trusses, rattling cars and the smell of oil and the sound of chains and ratchets). The entrance to the park, like another similar to it in Sydney was a large mouth gaping open to accept the passersby with the promise "Just for Fun."

The "ding dong" of mid-century pinball machines joined the acrid electric smell of dodgem cars, and the sweet sickly smell of cotton candy and popcorn permeated much of Luna Park. Between 1973 and 1976, between the ages of 10 and 13, I lived breathed, ate and drank Luna Park's fairground culture. It was possible to find tickets to rides thrown away around the park very easily and for several Australian dollars you could spend an entire afternoon there.

Videogames were something very new then, as were the arrival of electronics into everyday life. Tape recorders were things to covet and play with. The rise of progressive rock bands like YES and Pink Floyd with their amazing moog synths and mellotrons and other tape- and transistor-driven amplified utopias of sound/music/film/entertainmenat were all part of the culture.

At Luna Park there were still echoes of the early pre-war days in the form of penny arcade amusements (of the sort you can now see at the Musee Mechanique here in San Francisco)--miniature scenes of horror, execution, battle, and tests of strength. "Sex drive" measuring devices. Vibrating chairs. Vicarious thrills built from steel and brass in varnished wooden cases illuminated by dim 20-watt lightbulbs. These were things of true beauty and many had come all the way from Chicago.

On the big screens downtown at the cinemas were Kung Fu movies from Hong Kong, mechanical sharks, and Death Stars. Psycho-dramas on TV of the sort so well emulated today by Damon Packard (psychedelia for the masses) and San Francisco to me was a place where a fresh faced Michael Douglas cruised the streets with Karl Malden on TV. Life itself felt like a Quinn Martin production, complete with funky soundtrack and clavichord riff.

In the 1970's pool halls and pinball joints, and even my local Luna Park, were rough places. You entered them furtively, knowing that many of the young male customers were likely to be rough types and that you needed to kind of watch your back. The fact that I was in my early teens and usually with some friends meant that I was most probably likely not to get beaten up by skinheads. These were the kids whose only real choices were between a lifetime of dull and dangerous factory work, a life of petty crime, jail, or welfare.

Nothing to do, nowhere to go. Beer, cigarettes, pool, pinball and the occasional furtive sexual experience were what most of the older teen guys and girls were looking for. Some of the men were freshly returned from the bitterly contested war in (geographically speaking) nearby Vietnam, and were often very edgy and angry for reasons few could explain.

Videogames, like the penny arcades half a decade prior were, in a word, dodgy. And it was into into this rough & ready context of pinball arcades, amusement parks and hamburger joints that the first videogames--for me, at least--appeared.

The author in front of Luna Park amusement park, Melbourne, Australia 1974. My chopper bike then took me deep into a world of vicarious arcade entertainment.

With my friend Patrick I would routinely ride my chopper bike to places where the click of pool cues on balls rang out. The sound of a rack of pool balls falling onto the wooden guts of a beer-stained, ciggy-burned, felt-top table would interrupt the chatter, laughter, and angry insult. These were dark places where the tang of cigarette smoke and that of alcohol on long haired-guys (in jeans and jean jackets) huddled around cabinets of amusement and distraction. It was into settings like these that the first games to hit Australia--like 'Pong,' 'Night Driver,' 'Space Invaders,' 'Breakout,' 'Jaws,' 'Gun Fight,' and 'Boot Hill' appeared.

Then there were the Taito greats from Japan. "Space Invaders" was everywhere. Note, arcades were not called 'videogame arcades.' Rather we called them "Spacies." Whole arcades had nothing but spacies in them. Row upon row of nothing but this one game. Sit down ones. Cabinet ones. That sound, deafening 'dum, dum, dum dum' 'whoosh whoosh'....

Later in the decade there emerged the Atari classics, like 'Centipede,' 'Missile Command,' 'Lunar Lander,' 'Defender.'

Play them here: http://www.atari.com/play

The Midway games like 'Galaga,' 'Galaxian,' ate coins and seemed to represent some parallel distant place where Lukes Skywalked and Californian suns set on hot rods, the cold war, and the mysteries of distant utopian dreams of global mastery.

It was a time when computers needed cassette machines to store and play back data. You typed your games into a machine from code transcribed in BASIC in the pages of glossy magazines. The computers were the Sinclair Z-80, the Acorn Electron, the Commodore 64, The TRS-80. My geek friends and I would freely exchange 'datassettes' of games to run on our 'micro' computers, and would assume that to play games at home, we would have to actually write the code for them, line by line directly into our machines. Stores like Radio Shack had sections set aside for local kids to sell their games-on-cassette in ziplock bags with paper labels stapled to them. You pulled them off the wall and paid whatever the hand-written sticker said they were worth. $5. $10. Who knew what a good game was worth? With a medium so easy to copy, the difference between exchange value and and use value was totally blurred. In distant Slovenia, there were kids copying games right off the radio broadcast over the student radio system. Just one error in volume level, when playing the game data from a cassette recorder, meant the game would not load.

a 'datasette' drive from a Commodore 64 home computer - make sure the volume level is set just right!

In high school along with games-on-cassettes, we passed round copies of TIME and NEWSWEEK magazines and read articles about this place called 'Atari' in California. We thought up ideas for games, wishing that we could join the dope-smoking employees there. In 2006, I ended up working in exactly the same building we were then reading about back in 1979. By 2006 of course, the building had changed hands dozens of times and the longhairs of Bushnell's ill-fated Sunnyvale operation had long since grown old and been churned back into highway 101 and the mass of techno-deterministic dreams that twitch on the side of the road like road kill. It had been the home 2600 version of the game 'ET,' the legend has it, that finally did them in. All that dope smoke jacked their quality control. (...Six million units buried somewhere in New Mexico?)

When arcades started to appear for the sake of videogames alone, when nothing but videogames were in them, investors had done the math and worked out that operations could sustain whole roomfuls of cabinets. Operators could set the difficulty level of games like 'Defender,' and thus maximize returns based on the popularity of a game. For most of us teenagers this meant that much time was spent just watching other people play rather than playing yourself. This shared 'let's-see-what-games-came-out-this-week' became a kind of social relation in itself.

We celebrated the very existence of the games and played them when we could. Today a rare 'Defender' machine sits at Lost Weekend video rental store on Valencia street in San Francisco. (When Damon Packard was last in town, he and I spent an hour playing it and chatting, and were thus reconnected with a social experience right out of the 1980's.) It's something people of our generation, especially those of a certain arts/entertainment/popular culture/film/comics/sci-fi/TV generation, know how to do. Play arcade machines and chat. Its like old people in Italy playing chess out in the open.

For a sense of what the arcades were like, watch the original 'Karate Kid' movie. It does a great job of nailing the social role that arcades played at the time. 'TRON' does too, but in a more stylized way. 'Terminator 2' [also the first movie to seamlessly blend CGI elements! --ed.] shows a later version of the trend, when arcades started to become subsumed within the broader logic of shopping malls, where slowly the street elements of arcades were replaced by a token-and-prize based method of mediated the entertainment.

You were not so much putting quarters into machines from your own pocket. You were exchanging real money for tokens which in a sense codified the exchange into a level of rent--you rented a games space and paid your rent via stand-ins for real money. Real money is about you as a person, and money is your property. By exchanging money for tokens you have agreed to let the leased holding that is the mall extend its legal infrastructure to your relationship to an experience.

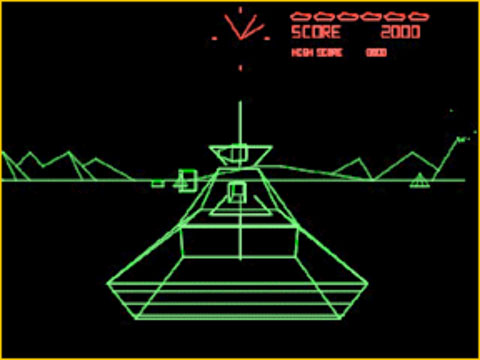

Vector graphics games such as 'Lunar Lander,' 'Battle Zone,' and 'Asteroids' spoke to a time--not so long prior--in the late 1960's when mainframes had driven development at universities and in government research. Vector-based games have their artwork drawn by the computer in real time. These are not bitmaps being animated, but rather whole screens of visual data, arrays of coordinate points made up of glowing white or green phosphor. They glowed from within, like a magic force and were a wonderful thing to experience.

To play a vector graphics game was to inhabit another dimension, made for you on-the-fly, as the game was playing. The vector version of the game 'Star Wars,' where you sat in a cockpit and flew through the trench to blow up the Death Star, felt like it had indeed come right from inside the film. Did not the lines and vectors defining this 3D world resemble the graphics used in the film at the end to demonstrate what Luke and his friends must do? Was this not thus a direct and authentic link to the mis-en-scene of the 'Star Wars' universe? (Were we not then automatically by default thus in the film when we played?)

When they appeared briefly on the scene in the late 1970's and early 1980's, vector screen games were linked directly to cold war military training. In high school I knew no one who expected to live to see thirty. Death from distant nukes was definitely going to happen. It was just a matter of time.

Videogames thus enacted a lived sensibility--felt keenly every day at this time--that we should live life to the full while we still could. This aspect of the 1970's is often neatly edited out of many mainstream depictions of the period, but it was a feeling out there, ambient (much like the contemporary post-9/11 sense that the heat is on and all around in the form of generalized official power, authority, and discipline).

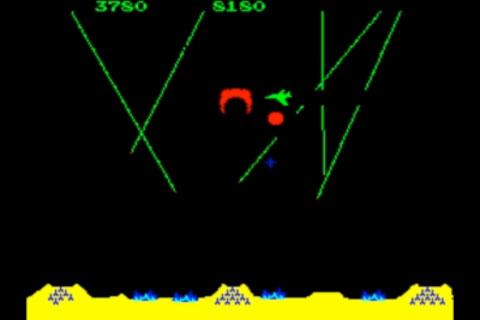

The theme of the cold-war era games included saving colonists from being zombified ('Defender'), saving cities from missile attack ('Missile Command'), and preparation for life off-world ('Lunar Lander'). The vectors glowed behind view screens that cupped the eyes and placed you right there inside the screen. 'Battlezone,' a tank battle game required you to put your eyes into a viewer that resembled the periscope of a NATO tank somewhere in the wide open fields of West Germany. Only this world was glowing green, had flying saucers and wire-frame pyramids and cubes to hide behind.

'Missile Command' by Atari - in the 1970s, nuclear war felt like a looming inevitable certainty.

By the late 1980's and early 1990's, the experience of going to the arcade was to be surrounded by an ever-increasing array of types of cabinets--jet fighter cockpits, car interiors, etc. Displays could include Laserdisc playback ('Dragon's Quest') and 'Time Traveller' (a 'hologram' game).

The bulky cabinet for the 1991 Laserdisc game 'Time Traveller' which boasted a so-called 'hologram' display (actually a clever way to project Laserdisc images using a mirrored lens into what appeared to be thin air).

'Time Traveler' graphics.

In Melbourne around the corner of Burke and Russell streets, a range of arcades emerged. There were four or five all within walking distance of a few hundred yards. There were the larger, well-funded double-story "family entertainment" centers where the latest games would always be placed near the sidewalk to attract passing lunchtime and after-work trade. Then there were the sleazier smaller operations where smoking guys played almost exclusively side-on fighter games. These were variations on 'Street Fighter' and 'Mortal Kombat.' Most had generic one-cabinet-fits-all cases with almost certainly Taiwanese-pirated knock-off games running inside.

At Swinburne film school in 1990 I flew an FA-18 Interceptor flight simulator (on the same Amigas we were using to do 2D--Deluxe Paint--animation) around a virtual simplified Bay Area. I spent all my spare time in 1990 and 1991 flying around this virtual San Francisco in my virtual FA-18. By the time I visited the place for real in 1992, I knew the spatial organization of features like Sutro Tower, both major bridges, and the length and significance--geo-culturally and militarily--of the bay itself, which stretches all the way down to where the planes took off (Moffett field).

Landing in San Francisco with my suitcase of films in 1992, the plane had a map projected in the cabin showing the contours of the Bay Area in exactly the same colors as that flight sim. Blue for water. Green for land. All diagonal and simplified, soon to be made considerably more complex by the act of getting out of a real plane and walking around the real city.

I learned an awful lot about the layout of the Bay Area from an Amiga flight sim before arriving here.

So back in the 1970's and 1980's I spent a lot of time in the arcades. Not always playing. Sometimes just walking around, taking in the ambiance. I was reading William Gibson, Umberto Eco. I was attending SF Cinematheque screenings, seeing a lot of experimental film, and teaching art to refugee kids from Vietnam for a living. These were post-modern times. Laurie Anderson music, David Lynch movies, Micheal Jackson videos, New Romantic culture; times of Zappa and walkmen, of Hal Hartley and Peter Greenaway. It was a time of cultural renaissance.

Daily life then was really like "Blade Runner"--all rain, neon, cigarettes; the romance of noir and electronics and crime. I was a young writer and film-maker marinating myself in the glow of the games machines, trying to connect these experiences with those from a time only ten years prior when I had just left childhood. In the glow of the square pong ball, I traced my recent history across the screen of my life. I too had been bounced around from one end of the globe to the other, from one country to another--the US, the UK, and now Australia. Technoculture and cyberculture were natural places for me to be and I embraced it all enthusiastically.

In the early 1990s I even worked at a videogame company called Beam Software. In addition to actually project-managing 16-bit videogames I was also doing on-the-job research for the Australian Federal Department of Science and Industry examining the role of the videogame producer. The feds paid half my salary just to write a lengthy essay "the role of the videogame producer." Seems the Aussie government wanted to know more about this new and growing sector of the economy (and I don't blame them).

My job was literally to study the games industry from the inside. I found the games business incredibly demanding in terms of time and energy and most of my duties as a project manager involved convincing other managers and publishers that the games on my watch were on schedule to meet the pressing demands of future Christmas deadlines. These were the 16 bit home console days--the Megadrive and the Super Nintendo--as well as the 8-bit Gameboy (where Beam's real profits lay). It was a time when the CD-ROM had just arrived and with it the introduction of consoles and game experiences that involved more and more video sequences, as well as the logic and interest of motion picture production culture. It was a fascinating time to witness.

'Blades of Vengeance' - a side-scrolling game by Beam Software for the Sega Megadrive - one of the titles developed during my time there as a producer.

One day at lunchtime in 1994 the whole company were playing a new game that let you see the playfield as from a first person perspective and, more importantly, let you connect this space via the local area network. 'DOOM' offered the first truly workable real-time virtual reality experience and represented the first time that the internet mediated the entire production, marketing, and sale of a game. You downloaded a demo on your 486. Played it. Then sent a check to Texas for the stack of floppies that was the entire game. As well as being an awesome game with lots of popular culture references, it was the beginning of the end of the idea of a game as something physical you bought like a can of soda. And the beginning of virtuality as the mediating element of both the game as well as the means of distribution and cultural deployment.

'Doom' - the first truly online game and the beginning of the first-person shooter genre.

Beam was an intense while also extremely rewarding experience and I am thankful for the chance to have been a part of an important moment in the history of the medium.

I discovered at Beam that I was really more of a scholar of games than a games production professional. Beam taught me the value of games as spaces and environments that needed mapping and inhabiting. On the basis of my experiences I later studied more in-depth how electronics mediate the overall urban experience. I built an online city, went to MIT to work with others doing similar work, and eventually got my master's degree in this field.

So I was always as interested in the theories and ideas behind games design as I was in the minutiae of how they are made and sold. I wanted then and continue to want today to fully understand games as a cultural force, and now at CCSF and San Francisco State University I teach an ever-growing enthusiastic group of students. We all learn as much as we can about what games are, where they come from, and what they mean culturally. We play the games, read about them, play them some more, write about them, etc. Games offer a solid basis for understanding the broader culture itself, mediated as it is increasingly by electronic systems and devices of extraordinary complexity and sophistication.

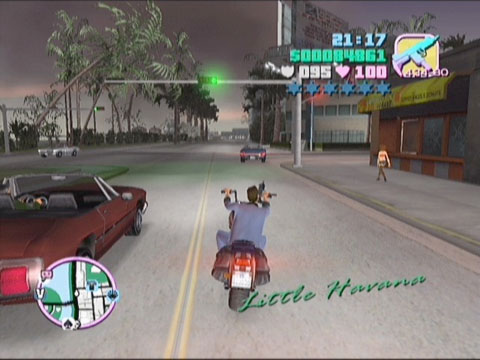

As I daily teach and play videogames, its not so much any given game from the past thirty years that that holds my fascination. I tend to play through retro games, to reach the feelings I had when I first saw them, first knew them. 'Grand Theft Auto' to me was the mid 2000s when the post-9/11 hell that were the Bush years were so perfectly summed up by the dry wit and laconic misanthropy of this series. 'GTA' is Bush-Era cynical satire that perfectly enacts the selfish amoral culture of the Republican agenda for the future--all crime, all death, all money, all corruption.

'GTA: Vice City' in particular was a British take on US culture. Rock Star North are Northern British kids riffing on a US they have only experienced through TV and movies, and it makes for better entertainment as a result. You get Euro-irony as the secret ingredient to better understand the realpolitiks of a gangster simulator.

Satire of the 'me-first' Bush-era USA from a Northern British perspective - GTA Vice City for the Playstation 2.

Now a thousand flowers bloom and games are more an individual art than they have ever been. They have spun off into fascinating movements like chiptunes and the personal narrative game. Games are now interwoven into every aspect of life.

Games and life fuse more and more each day. They are the air we breathe. Our lives follow gameplay modes. We enter playfields as we walk down the street. Pickups and spells and power-ups pepper the landscape of our daily lives. The social media mavens have discovered the idea that games are an extension of the advertising-and-public-relations-driven orgy of marketing that has slowly but surely taken over every aspect of online life.

The commercial games industry has grown bloated on its own success. The enormous tens-of-millions of dollars spend on "A-List" titles has made the mainstream business so risk-averse that only absolutely proven titles are approved. Exceptions to this rule are few & far between. Some gems appear here & there: like the extraordinary "Scribblenauts," a genuinely innovative game for the Nintendo DS that fuses literacy with fantasy role play. Or the growing plethora of game-as-art poems that circulate as java games online. This, the Ipad era, is a good time to make indie games--and there is room for everyone.

"Scribblenauts" - genuine but rare contemporary videogame innovation for the Nintendo DS from 2009.

Many games today designed for use on websites, or for 'smart' portable devices, are framed as little more than bait for ads. (Or bogus 'in-game-power-ups' which are, in turn, more bait for ads.)

The real estate and hospitality industries, with the help of merchants and other urban redevelopment interests have fused with new models of online sales channels. The result is an ever more homogeneous experience at every level of urban life. You get up to face a less interesting and more managed city, use your closed-system devices on controlled gateways to a censored internet. Through ever-more powerful social media tools and search engines you are steered into buying 'apps,' which in turn render the end user merely a plug-in to an ever more homogenized lived urban present.

The contemporary gamer is today a user. This user is imagined (by those backing the games s/he will play via facebook/twitter (et al)) to be cashed-up and professional, and to be yearning for an ever more privatized, domestic, and closed 'safe' world away from the dangers of a diverse street life. Videogames in this scenario do not so much distract from a life of drudgery, but merely reinforce the all-pervasive boredom of a life devoid of diversity: homogeneous and safe, risk-averse and inherently conservative.

Games-as-ads and "apps," which fuse spending-habit and web-browsing data with interactive casual gaming, have little to do with what games were about back in the 60s and 70s. The 1970's today can never be lived, only experienced as a kind of 'plug-in' to life. A fashion statement, an empty gesture. A thirty-year anniversary boxed-set.

It's a 'look.' Games are now part of the all-pervasive and increasingly less-than-fair and open Google-plex. Games are more and more an extension of the immature and merely two-pixel-thick Facebook version of "friendship"-- shallow, meaningless, and cut out of life. Videogames today appear sometimes as little more than a hip background hum to the empty posturings of (don't-even-know-they-are-doing-it) gentrifying trust-fund hipsters!

Most of the people rapidly developing social media games were not even born when the golden age of gaming was in full swing. It's a pity because they could have learned something of what real urban social culture was like before the interests of cool-hunting market research decided that the demographic for games was just the 'in' they needed to sell more energy drinks, overpriced t-shirts, or the latest obsolete-within-a-year gadget.

Games as I understand them are not an "app" for overpriced devices bought from online stores with high-balance credit cards. They were (and in many parts of the world still are) part of a directly-lived experience of a city alive with possibility.

Every good 1960's Godard film has a pinball machine in it. Young people in Paris almost fucked their pinball machines. Tilting the machine, or risking a tilt was assumed to be part of the gameplay. You humped the thing, literally got off on it in public.

Every authentic life lived on the street has known what videogames are at their core really about. They are the expression of the danger of the street itself, right there on the sidewalk, just outside the arcade. The joystick is the interface to the game but the game is the interface to the street itself. (And if your life is the street, then the game is the interface to your life.)

William Gibson coined the term 'cyberspace' when he saw how rapt the kids were on Granville street in Vancouver playing their arcade videogames. I know the very amusement halls he visited. They were still there in the early 1990s and they fused sleaze, fun, and weirdness like no other I've been to before or since (--70's era black-curtain-clad coin-operated 16mm porn loop cabinets sat casually next to arcade classic games!!).

Gibson said it was as if the kids really believed there was a whole world on the other side of the screen--one which they were hungering to enter and be part of. And if all those screens were connected (as indeed they now are) then the whole connected space was something to be navigated. Something Kyber, or Cyber--which is greek for 'to navigate.' Hence Cyberspace. Videogame arcades started the very idea of Cyberspace.

Early in my career I learned that there are two kinds of games--those with patterned gameplay and those with random gameplay. The former are games where you know what will happen next and you get better at playing the game based on the same-every-time pattern. ('Space Invaders is a patterned game. 'Time Crisis' is another.)

The second type are games where each new wave of enemies is different from the last. 'Tetris' is such a game. (--What shape will emerge from the top of the screen next?) In the late 1980s, moved deeply by watching leaves fall upon leaves and fish bury themselves in sand, Alexei Pajitnov in then still-Soviet Russia, developed one of the most beautiful electronic metaphors for work-that-is-never-finished in his masterpiece puzzle game 'Tetris.' He can still charge US$5 for every version sold online for every phone and device!

Life is very much a combination of patterned and random gameplay. And a meaningfully lived life has another built-in feature: dynamic play adjustment.

The game gets harder to play the better you get at playing it.

[Thanks to Monty and Craig at OZ.]

◊

LINKS

Exploring Game Worlds Blog (my Fall 2010 class at CCSF) - syllabus included - sign up for Spring 2011!!

This super-rare black and white mid-1970s TV commercial shows the amusement arcade at Luna Park in Melbourne that I remember vividly. I would have been about 10 years old when this ad was flmed. The glam-rock fashions shown were popular with teens and adults at the time. Notice how many mid-century amusement cabinets are visible in the background. Videogames had yet to arrive in this era of mechanical, solenoid-and-relay switch driven coin-operated amusement machinery:

GAMASUTRA http://www.gamasutra.com/

Play Classic Atari games online here: http://www.atari.com/play

This animation of a 1984 videogame arcade does a great job of summing up the sounds and feel of the period, with many titles and cabinet art from the 'golden age'

http://cinemarcade.com/arcade84.htmlPlay Pong online at this BAFTA site:

http://www.bafta.org/awards/video-games/play-pong-online,678,BA.html

Read about the story of Pong here:

http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3900/the_history_of_pong_avoid_missing_.php

The Dot Eaters - the best videogame history site on the web:

Play DOOM online - its 1994 all over again:

http://www.aceshootinggames.com/play/games_list/doom.htmlMusee Mechanique site - excellent museum at Fisherman's wharf with some of the finest amusement arcades and classic videogames from the past 40 years:

http://www.museemechanique.org/

Doug Engelbart and the mother of all demos:

Some good books

Poole, Steven, Trigger Happy: Video-games and the Entertainment Revolution, Arcade Publishing; ISBN: 1559705396

Download this fantastic above book for free from here: http://stevenpoole.net/blog/trigger-happier/

Demarla, Rusel, Wilson, Johnny L, High Score: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games, McGraw Hill/Osborne, 2002

Burnham ,Van, Supercade : A Visual History of the Video game Age, 1971-1984 MIT Press; ISBN: 0262024926

Saltzman, Marc, (Ed) Game Design: Secret of the Sages Brady Games; ISBN: 1566869870

Sheff, David, Eddy, Andy, Game Over Press Start To Continue GamePress; ISBN: 0966961706

Sellers, John, ARCADE FEVER The Fan's Guide to The Golden Age of Video Games ISBN: 0762409371

Stansberry, Dominic, Labyrinths: The Art of Interactive Writing and Design, Content Development for New Media (June 30, 1997) Wadsworth Pub Co; ISBN: 0534519482

Turkle, Sherry, Life on the Screen : Identity in the Age of the Internet (September 1997) Touchstone Books; ISBN: 0684833484

Bates, Bob, and Lomothe, Andrew (Ed): Game Design : The Art & Business of Creating Games (May 2001) Prima Publishing; ISBN: 0761531653

Rouse, Richard, Ogden, Steve, Rybczyk, Mark Louise, Game Design: Theory and Practice (With CD-ROM) Paperback - 500 pages Bk&Cd-Rom edition (February15, 2001) Wordware Publishing; ISBN: 1556227353

David Cox is an award winning film-maker, digital media artist, writer, and cultural critic who has lived and worked in Britain, the United States and Australia. His films include OTHERZONE, PUPPENHEAD and BIT. He obtained his Masters Degree in 2003 from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University, in Australia. He also holds a Graduate Diploma in Applied Film and Television (with Honors) in 1990 from Melbourne's Swinburne School of Film and Television and is currently undertaking a PhD part-time at the University of Technology, Queensland Center for Cultural and Critical Studies, Australia where his thesis topic focuses on the history of media. He is currently also teaching computer skills within the Interdisciplinary Studies Program at City College in San Francisco.

David Cox is an award winning film-maker, digital media artist, writer, and cultural critic who has lived and worked in Britain, the United States and Australia. His films include OTHERZONE, PUPPENHEAD and BIT. He obtained his Masters Degree in 2003 from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University, in Australia. He also holds a Graduate Diploma in Applied Film and Television (with Honors) in 1990 from Melbourne's Swinburne School of Film and Television and is currently undertaking a PhD part-time at the University of Technology, Queensland Center for Cultural and Critical Studies, Australia where his thesis topic focuses on the history of media. He is currently also teaching computer skills within the Interdisciplinary Studies Program at City College in San Francisco.

davidalbertcox@gmail.com