Uncovering the Enigmatic Harry Partch

24 Sep 2011

I am first and last a composer. I have been provoked into becoming a musical theorist, an instrument builder, a musical apostate, and a musical idealist, simply because I have been a demanding composer. I hold no wish for the obsolescence of the widely heard

instruments and music.

My devotion to our musical heritage is great and critical. I feel that more ferment is necessary to a healthy musical culture. I am endeavoring to instill more ferment.

-Harry Partch, 1942

My professor had only a cursory knowledge of Partch, so I was left to my own device to figure out who he was. The first recording of Partch's that I got my hands on was an early version of "Barstow: Eight Hitchhiker's Inscriptions," which took its lyrics from hobo graffiti he collected while stuck in Barstow, and featured instruments and a manner of speech/singing that I had never encountered before. He was doing what I was attempting to do, but this was organized, it was fresh, and it had been recorded sixty years before.

Bob Gilmore's fantastic biography on Partch was my next stop, along with the Enclosures series that Philip Blackburn produced for Innova recordings, and I was hooked. I looked for a film on Partch, and found a few things, the most interesting ones featured Partch as a collaborator (see "Music Studio" and "The Dreamer that Remains"). But there was a startling lack of posthumous documentary exposure, which I believe is the reason so few people know of Partch, his instruments and his music. There was a BBC 4 documentary, mostly rubbish, thrown together by a small crew in a rush, which painted Partch as some old alcoholic white-bearded guru. The BBC doc and a lot of the articles I read seemed to perpetuate myths about Partch as a self-taught Hobo Composer with no university affiliation. I saw through the bullshit relatively early on, and that led to my cause-to make a comprehensive documentary about the entire life of Harry Partch-to debunk the myths, explain where he came from, and create the portrait of the artist that I would have wanted to see.

His ideas forced him to be an outcast in a way, from academia and from other musicians. His ideas about music and tuning stretched back to Ancient Greece and China and all the way up to Helmholtz and the study of acoustics?this is a difficult pill for a lot of music theorists to swallow.

In the course of my research I was amazed at just how complex a man he really was, and how much of that was on account of his early family life. His parents were Presbyterian missionaries based in China and right before Partch was born, they had to leave due to the Boxer Rebellion. They settled in Oakland and soon moved to the desert in southeastern Arizona, near the border of Mexico. His father was a quiet man who lost his faith and his mother remained devout, and was an outspoken suffragette to boot. Partch ended up losing both of them before he was 20 years old. He lived a transient lifestyle for a number of years and this wasn't always by choice, even though some like to romanticize it. During the Great Depression he lived as a hobo and traveled around notating hobos' speech patterns that he would later weave into his music. After he devised his tuning system, and settled on his 43-tone just intonation scale, and of course, after he built the array of instruments that he needed to play his new music.

His ideas forced him to be an outcast in a way, from academia and from other musicians. His ideas about music and tuning stretched back to Ancient Greece and China and all the way up to Helmholtz and the study of acoustics?this is a difficult pill for a lot of music theorists to swallow. A lot of people like to live in the realm of 12-tone equal temperament, which has only been around for a few hundred years, with JS Bach as their personal lord and savior. And when you start challenging that, it makes some people a little uneasy. Even with the musicians who embraced his music, he still had to work around the problems of notation and the physical interaction with the instruments he demanded. Partch at times could be very convincing and very charming but he could be equally as abrasive and push people away. So I think while he wanted to maintain institutional affiliations, often times when they were presented, he would wear out his welcome and just have to move on to the next place.

Partch was an iconoclast, because he not only set his own rules, he changed the game. In retrospect it seems that he's opened doors for a lot of different kinds of sound-artists, musicians, and composers. Partch's compositions, as well as his contribution to music theory, his book "Genesis of a Music," has allowed for music to go in a lot of different ways by making a connection between very ancient ideas and very modern problems. He embraced the fundamental Ancient Greek concepts of Monophony, Pythagorean tuning, and the total integration of music/drama/poetry/dance into a single art form. And we see in the 20th century and now in the 21st, people like Ben Johnston who took the idea and went in a different direction with it. He took Partch's theories on intonation and generalized them, and used it in his chamber music. So now we see just intonation coming from a lot of different composers, and I think that's a good thing, I think that's an amazing thing. And I think just now we are starting to realize the importance of Partch.

From the grave, Harry Partch has provoked me into becoming a documentary filmmaker. It's been my goal from the beginning to have a film that would be a companion piece for Philip Blackburn's incredible Enclosures series and for Bob Gilmore's book on Harry.

The quote at the beginning of this article tells that Partch was provoked into becoming a music theorist and an instrument builder for the sake of his duty as a composer. From the grave, Harry Partch has provoked me into becoming a documentary filmmaker. It's been my goal from the beginning to have a film that would be a companion piece for Philip Blackburn's incredible Enclosures series and for Bob Gilmore's book on Harry. And if someone can watch this film and pick up the book, and start reading about it, or go and buy some Partch records, then I feel I've done my job. Because it's become more than just a film to me, it's something I believe in, and it's changed me, and made me a better person and a better artist. To this day, Partch, because of his creativity and refusal to conform, remains an inspiration to me, but also a constant reminder of the trials that one who bucks the system will ultimately endure.

* * *

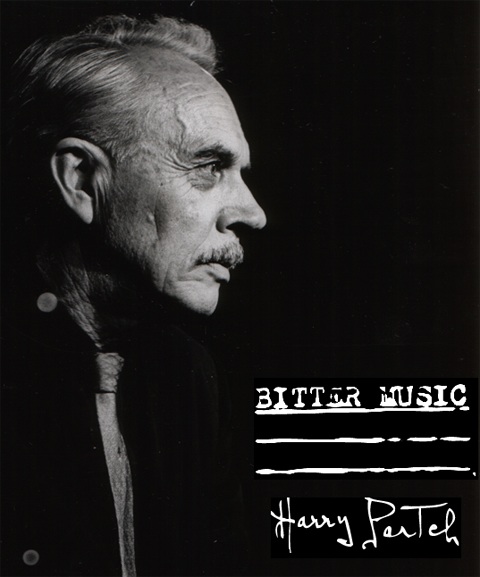

Bitter Music dir. Jon Roy

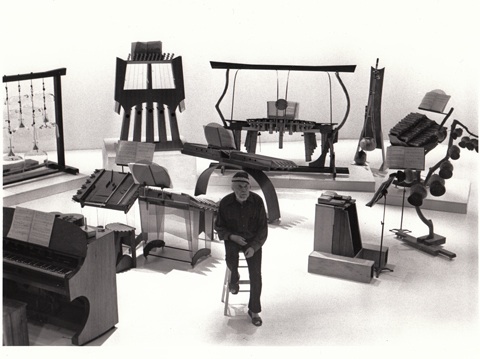

Bay Area native Harry Partch (1901-1974) was an iconoclastic composer

of music, who early in his career abandoned traditional Western

musical instruments and scales, and settled instead for a 43-tone-to-the-octave

scale, borrowing on ancient tuning practices. Over a lifetime he

designed and built an orchestra of instruments to play his music, but

always regarded the human voice as the primary instrument. This

documentary excerpt will highlight Partch's music, instruments, and

performances. Bitter Music plays at OTHER CINEMA on Saturday, 12/3

at 8:30pm.