Who is Bozo Texino: a Search with Bill Daniel

7 Feb 2007

An interview with filmmaker Bill Daniel about Who is Bozo Texino?, a investigation into the secret history of hobo graffiti.

First Stop

So, on the surface of it, we have a few clues. A name, perhaps a face. A few lines, sketched on the side of a moving train.

So, on the surface of it, we have a few clues. A name, perhaps a face. A few lines, sketched on the side of a moving train.

It goes by fast, but you have to look closely to see them: a different set of answers, to a different set of questions. Get ready as it passes through your station, not stopping, but slowing enough for you to jump aboard, into a strange past that’s not present, a strange present that’s not passed.

I. Who is Bozo Texino (The Art)

Bill Daniel: I saw the graffiti well before I started riding. This was before I went off the deep end on trains, riding them and being interested in the history. It was just the graffiti, raw, like, what the hell was that, you know, I’ve never seen a mark like that! And then I started seeing more marks like that and I realized, there’s something going on, there’s a group of people that I’ve never heard of, and they’re doing something.

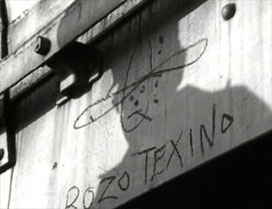

It’s a name, inscribed in chalk or oilstick or marker, on the side of a train, with a simple line drawing, a face in a hat, stylized through repetition: 6 lines, 6 dots. Pause. Repeat.

It’s a name, inscribed in chalk or oilstick or marker, on the side of a train, with a simple line drawing, a face in a hat, stylized through repetition: 6 lines, 6 dots. Pause. Repeat.

Accompanying it on its journey, besides repetitions of itself: other lines, other names. Other drawings. What are these signs? Who makes them? Who, and why?

BD: And as it turns out, they’re not so much a group of people as just a number of individuals engaging in this same practice. They are kind of communicating, participating in a scene, in a collective practice, but almost none of these people in my film – none of them! – knew who the other people were. They were literally so anonymous as to not know each other. And a lot of times they had really inaccurate ideas of each other, especially between the tramps and the rail workers. Tramps and rail workers are very different people: demographically, economically, and even psychologically, in their reasons for writing on trains. So there is an impulse to humanize the landscape and to make your mark, but there are different groups of people engaging in this practice.

Something needs to be at our scale. In any landscape, natural or manmade, we need to create places to stop, pauses and parenthetical remarks in the overall scope, corners to get one’s bearings, to define and refine one’s small volume in all that space. Part of the challenge is to manage immensity at the same time as intimacy. To leave a mark, a drawing, some words, your initials, on the edge of something larger than you is to create a dialectics of scale, to posit a relationship between the large and the small that attempts to comprehend vastness and freedom, that attempts to establish your place in both outer and inner space.

Something needs to be at our scale. In any landscape, natural or manmade, we need to create places to stop, pauses and parenthetical remarks in the overall scope, corners to get one’s bearings, to define and refine one’s small volume in all that space. Part of the challenge is to manage immensity at the same time as intimacy. To leave a mark, a drawing, some words, your initials, on the edge of something larger than you is to create a dialectics of scale, to posit a relationship between the large and the small that attempts to comprehend vastness and freedom, that attempts to establish your place in both outer and inner space.

BD: Mark-making, name-making, name-giving, character-drawing: ‘monikers.’ That is a great name for them, monikers. That name finally formed and stuck pretty recently, people had called them all different kinds of things over the last 20 years, like ‘hobo tags’ or ‘streakers.’

Peggy Nelson: I’m surprised there are still hobos.

BD: Well, you could say there are not. You could say that the hobo died with WWI. Or in the ‘30s; that those people weren’t hobos, that they were displaced citizens, that they weren’t there by choice. One of the definitions of hobos is that they are there by choice, like a professional vocation.

[The hobo lifestyle] is kind of a myth. My film is really a kind of comic book: people are talking about a way of life but you’re not really seeing that way of life, because there’s so little of it that actually exists. There are very few people still practicing this thing, so it’s odd to talk about it in the present tense. When I first started the film I saw it as a salvage ethnography project, like I’m going to bear witness to this dying practice. But it’s been dying for a long time. And it’s so suffused with its’ own mythology that in a sense it is not a way of life.

The hobo way of life has been “dying out” almost as soon as it began, a claim made most often by the hobos themselves. Hobos practice a lifestyle in defiance of the fact that they themselves claim it no longer really exists, and has not in a long time. This defiance stakes a claim in mythology: to be a hobo is also to play the role of a hobo, to be an actor in a romantic saga of individuality and the open road.

BD: The film is a story about other people’s stories. You couldn’t really do a documentary about something that hardly exists anymore. It’s a documentary about the mythology of a way of life. The mythology persists, and people are engaging in that myth by riding trains and practicing monikers, but the socio-political landscape now is so different.

II. Who is Bozo Texino (The Artist)

But beneath the myth, there is the man. Someone is making these marks, someone in real time and real space. Who is it? Does anyone know?

But beneath the myth, there is the man. Someone is making these marks, someone in real time and real space. Who is it? Does anyone know?

The answer is, emphatically – maybe. Everyone the film meets knows who Bozo Texino is, but for each person he’s someone completely different. Everyone remembers a man who was old, young, Mexican, white, friendly, secretive – far from there being too few clues, there are far too many. They all point in different directions, to different people, whose identities pull away upon approach.

But a dynamic system does not stay indefinite forever. Eventually, you pick a train, you hop on board, and you go. In the act of asking, the question jumps to an answer. So too with the film: searching for Bozo Texino finds a Bozo Texino. He is interviewed, he has a scrapbook of photos of drawings on trains, he can even draw the symbol blindfolded. But neither the name nor the symbol is original with him, he claims to have taken the name from a previous artist, who perhaps saw it somewhere else, and other people may have picked it up as well. So is he Bozo Texino? Sure. And probably so were a number of others – or not. On the surface of it, “Who is . . .” does not have the simple answer we’d expect. Bozo Texino isn’t an original symbol tied to one individual. He’s an assemblage, his lines and dots collaged together out of other stories, other places. And picked up by others in their turn.

BD: But it’s not just creating an identity, it’s creating an identity that also has an articulated stance against the dominant culture, one that takes into account economics and a class critique. That has historically been part of hoboing: the Wobblies and the radical labor movements in the ‘30s, hobo causes, all that has been an important part of it.

However, I think that important things about that culture, like the radical self-reliance, the self-identifying culture, the self-naming of individuals and the creating of a separate code of ethics and behavior, are things that are going on right now in society in a lot of different places, but not in freight-riding necessarily. More interestingly I think that is happening in activist groups and in any number of bizarre underground communities, like car culture, lowriding, or backyard wrestling in Southern California. Any kind of self-created underground culture like that I think is probably a better example of contemporary practice.

So on the surface of it – but there are many surfaces.

Like all myths, uncovering its origins is no longer possible, if indeed it ever was. But the origin story is not perhaps the most interesting one. The collage of impressions and voices combine to tell a story much closer to home.

III. Who is Bozo Texino (The Quest)

Bozo Texino is a mystery. He slips, Rashomon-like, between the multiple tellings of his tale. The overlapping interviews, faces and voices, are certain in their contradictory claims, accumulating a collage of oral histories and a sense of experience, but no certain knowledge. But “Bozo Texino” the film is also a mystery, feeding us clues and challenging us to piece them together. As such, it is the story of the search, and the searcher; the missing protagonist becomes the director himself. He is present but absent, similarly to how the hobos are really physically there but at the same time inhabiting their own mythology to such a degree that they’re not actually there at all.

Bozo Texino is a mystery. He slips, Rashomon-like, between the multiple tellings of his tale. The overlapping interviews, faces and voices, are certain in their contradictory claims, accumulating a collage of oral histories and a sense of experience, but no certain knowledge. But “Bozo Texino” the film is also a mystery, feeding us clues and challenging us to piece them together. As such, it is the story of the search, and the searcher; the missing protagonist becomes the director himself. He is present but absent, similarly to how the hobos are really physically there but at the same time inhabiting their own mythology to such a degree that they’re not actually there at all.

The overlapping hobo stories combine to answer a different question. In telling their own stories, they are really telling his. Who is Bozo Texino: well, who wants to know?

The search for Bozo Texino is further echoed in the visual structure of the film, where recognizable patterns and objects are initially obscured by abstraction. A formal beauty found and lost, and found again in the next frame. A mystery posed and resolved in each shot, each beginning another step into the unknown.

BD: I started in still photography, and for a few years my photography was really about sequencing and building these kinds of ‘filmstrips.’ I would expose a roll of film with multiple frames to create sequences and patterns that suggested cinematic change, and use compositional patterns that you’d view left to right. All my early films were abstracts: cineplastic, motion-and-pattern things. I’d get stoned and put on the walkman, industrial music, and walk around a burnt building shaking the Super 8 cameras in patterns. I wasn’t long out of that by the time I started working on “Bozo Texino” in ’88 or ’89.

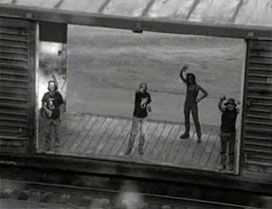

It’s hard to get a boring shot of a train. Trains are just so cinematic, you have to give the trains a lot of credit for their own kineticism and their awesome relationship to cinema: that linear, sprocketed, strobing, shuttering action of trains. It’s an awesome physical mechanical analogy.

IV. Who is Bozo Texino (The Film)

Touring.

Daniel decided to exhibit the film by touring, literally packing the components of a portable theater in his van and driving it around the country. Which reveals another parallel between the filmmaker and his subject, and not only in their attraction to motion. Showing the film in a different place every night inscribes a mark on each town, and echoes the practice of hobo graffiti. Touring leaves traces in the imaginal landscape instead of the one made of metal. But after all, the one made of metal exists on an imaginal level as well. As there is metal in film.

Daniel decided to exhibit the film by touring, literally packing the components of a portable theater in his van and driving it around the country. Which reveals another parallel between the filmmaker and his subject, and not only in their attraction to motion. Showing the film in a different place every night inscribes a mark on each town, and echoes the practice of hobo graffiti. Touring leaves traces in the imaginal landscape instead of the one made of metal. But after all, the one made of metal exists on an imaginal level as well. As there is metal in film.

BD: The idea of touring was there from the beginning, from dealing with bands and traveling with bands. So it just seemed like a natural thing to do. I’m not a fan of festivals or the whole festival scene, I’m not a fan of the corporate-controlled marketplace for either television or theatrical stuff, and I don’t go there to see films. I see a lot of films but I almost never see them in theaters and I definitely never see anything on television. The idea of making something for that market just doesn’t occur to me, and definitely doesn’t appeal to me. So what’s left is participating in a microcinema circuit, which is groovy and going on and getting better every day, but it’s still limited, it’s still kind of a ghetto.

The easiest audience to get doing this kind of work is an audience of peers. And that’s great, but a screening of mainly filmmakers in the audience is not necessarily what I ultimately want. I love my community, but I definitely want an audience that’s out there. In a sense, I want a mass audience, I want a mainstream audience, I want an audience that’s absolutely as broad-spectrum as it could possibly be.

That’s the challenge of trying to book these shows, and the work and risk of finding unusual weird places, and of finding novel promotional strategies. And it’s super labor-intensive, like putting up posters. It’s quite likely that 20 posters put in awesome places, like the choice billboard in the cafe or the light pole where tons of people are walking by, 20 might get you one person maybe, or it might take 100 to get one person. But to me, that one person that wouldn’t find you otherwise is a treasure to be opened: to get these people that don’t get the Cinematheque calendar.

Mythology.

BD: Radical self-reliance is one of the major themes of this film, it is definitely the strategy of making and distributing the film, and it’s how I live – to a fault, I’m sure! There’s a liberty and a power of mobility that you get in not waiting for money, or other things. One of the essential things about the hobos is self-reliance, you can hear Roadhog talking about that in the film in his kind of corny hobo philosophizing. You see less of it now in the world of people riding trains, it’s so much not what it was. But these ideas are still living on.

We tell each other stories about possibilities, for identity and action, dreaming and doing; and about limits, consequences and warnings, danger and risk. From an abstract perspective, we gather these under the heading of “myth,” with film being its contemporary repository, a place where the stories can grow and thrive and capture our imagination.

We tell each other stories about possibilities, for identity and action, dreaming and doing; and about limits, consequences and warnings, danger and risk. From an abstract perspective, we gather these under the heading of “myth,” with film being its contemporary repository, a place where the stories can grow and thrive and capture our imagination.

Except film does myth one better. The origin of the myth might be lost in time or in conflict, but the origin of the film is not lost; it is something known down to the last detail, especially by the filmmaker. In assembling images and sounds a film is constructed out of known elements, piece by piece. Jung observed that our spirituality is so impoverished that we see the gods as archetypes. But archetypes are types of characters, and film turns Jung’s pronouncement on its head, so that we can be liberated rather than impoverished. Film opens up myth to more direct and overt creative manipulation. What stories do we want to tell: about who we are, about who we can be, about what kind of society is possible? D-I-Y Olympus is documentary, not fantasy.

The Politics of Collage.

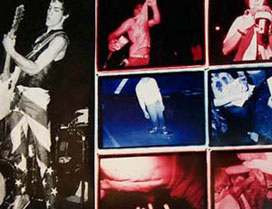

One of the types of creative manipulation in Bozo Texino is collage, something the film shares not only with the hobo lifestyle, but with Daniel’s other work. From early pieces like the Butthole Surfers, where multiple strobes both fracture and reassemble the image, to Bozo Texino and its multiple stories and points of view, to previous and future installations with their multiple images or projections, collage emerges as a common thread.

One of the types of creative manipulation in Bozo Texino is collage, something the film shares not only with the hobo lifestyle, but with Daniel’s other work. From early pieces like the Butthole Surfers, where multiple strobes both fracture and reassemble the image, to Bozo Texino and its multiple stories and points of view, to previous and future installations with their multiple images or projections, collage emerges as a common thread.

BD: “The Girl on the Train in the Moon” was one of the installation versions of “Bozo Texino” before it was finished. It was a totally nonsynchronous, two-screen piece. It would start whenever, it never had a specific starting or ending point, it was designed for a gallery situation where people just walk in on it. But obviously I presented it on tour, so I would just start the DVDs somewhere in the middle. They have different links so they would cycle differently, and the images would always be different, playing against each other. The audio track was wild, also. So that piece was really loose narratively.

While making “Bozo Texino,” when I was finishing it as a single channel thing, I kicked back and made these installations. But now I’m building installations first, with the idea that sooner or later I’ll make a linear piece. It’s not an efficient way to make a film because I have no idea what the final film is going to be like, you know? Eventually I’ll be able to make a film, some kind of film, but that film is only going to be what I manage to get between now and then. Neither Santa Claus nor the Tooth Fairy is going to come along and give me money to make a feature. But I can piecemeal-assemble these parts. What will end up happening is much like the way “Bozo” was made as a kind of found footage film; I’ll take stock of what I’ve got and see, well, what can I make out of this?

PN: Your own “found footage?”

BD: Yeah, right. Rather than things shot for a specific purpose, they’re shot because of the kind of value they have. They’re there because these are things I’m thinking about when I choose the story and when I choose a way to approach it and film it, and when I choose questions to ask an actual documentary interview subject, but certainly there’s no script.

The “Sailvan” is the third or fourth installation version of an ongoing project called “Sunset Scavenger,” which is about peak oil and climate change, economic and social collapse, and the end of one world and the beginning of a new one. I’m playing off a bunch of themes like Noah’s Ark, a doomsday kind of personality who’s sounding the alarm, and then also people who represent the making of the new world. The unofficial making of the next world. I’m finding them in punk activist communities. What’s going on with Common Ground in New Orleans is an awesome blueprint for making a better world, and it comes out of this apocalypse that’s fossil fuel fallout, which is what Katrina is. So, right now “Sunset Scavenger” is a collection of stories that I’ve just collaged together in a rambling essay format, on two screens, and pretty much nonlinear, although it has a stop and a start. I start the DVDs at the same time, and since they were edited in a timeline together I know what’s on one screen and then the other. But it’s a little loose because they’re not synchronous DVD players. And I’m using all 4 audio channels now, so I’m creating more of an environmental atmosphere, and then bouncing the voices and the foreground sounds around the two middle speakers.

PN: And you’re also working on a book project, right?

BD: The first artistic endeavor I ever had was taking pictures of punk bands. Silly as it sounds, but it’s true, punk rock saved my life! Or ruined it depending on how you look at it, I’m sure my mom thinks that it’s ruined. Between ‘80 and ‘84 I shot 400 rolls of film, still photos, of bands playing in Austin, Texas and California. I’m working a book called “Texas Punk Pioneers.” I put together a tour of this in 1999 and took it on the road, a one night hit-and-run film and photo show. I’d install between 200 and 300 photos in a gallery or community space for one night, and then boom! pack it back in the van and then zoom to the next town. So hopefully sometime in 2008, probably late 2007, the book will be done, and I’ll be touring with that. It will be one-night shows and also gallery shows; I’m looking for galleries to host more traditional month-long exhibition runs.

V. Who is Bozo Texino (The End)

That which is not slightly distorted lacks sensible appeal, from which it follows that irregularity – that is to say, the unexpected, surprise and astonishment – is an essential part and characteristic of beauty.

—Charles Baudelaire

Hobo life, skateboarding and punk rock are not only things that are not beautiful in any conventional sense but are, especially the latter, theoretically and directly opposed to the notion of beauty. The aesthetic pleasure derived from these pursuits is paradoxical and theoretical, rather than visual, in that they are standing for a certain kind of principle in opposition to what are seen as repressive and poisonous limitations and conventions in society.

Hobo life, skateboarding and punk rock are not only things that are not beautiful in any conventional sense but are, especially the latter, theoretically and directly opposed to the notion of beauty. The aesthetic pleasure derived from these pursuits is paradoxical and theoretical, rather than visual, in that they are standing for a certain kind of principle in opposition to what are seen as repressive and poisonous limitations and conventions in society.

To embrace these principles both in themselves and as subject matter is an act of resistance. Yet to represent them beautifully is an act of affirmation. There is a contradiction here. But the best art is large enough to contain such contradictions.

Last Stop.

So on the surface of it, things shift. The cars move faster, the image blurs and we look away; and in that instant, one world ends and another begins. Each frame gives us a moment where we can choose, and change. Perhaps such optimism is only found in the world of myth. But these days, that world is wide open and under construction. And there is a train leaving now.

BD: The world that we’ve made makes no sense. I just don’t like the way we’ve constructed our world! All my work is about an opposition to that, or the making of another world. The biggest issue we’re dealing with right now of course is energy, and it has been the whole time, we just didn’t realize it.

A lot of my work has to do with making a living, or providing for yourself, or self-reliance. I believe that what a person does, matters. And to the degree someone participates in the corporate world they’re insuring its dominance over us.

Keep up with Bill Daniel at www.billdaniel.net.

◊

Peggy Nelson is an artist and filmmaker who writes occasionally for OtherZine. She can be reached at www.peggynelson.com.