Poetics of an Urban Darkness:

Takashi Ito's Spectral Cinema

15 Feb 2011

"I cannot help feeling that some mysterious force is upsetting our emotional balance. The theme of my work over the last few years has been the portrayal of this sense of unease. In this work I seized on a very negative image of Tokyo and tried to portray the emotional state of people struggling and suffering in this very superficial world." —Unbalance, Takashi Ito, 2006.

The artist and his ghost

HALFWAY INTO TAKASHI ITO'S EXPERIMENTAL SHORT The Moon, we see the shot of a young boy smiling. He beams straight into the camera, as if he was responding to his father's joke. However, we are not really looking at the smiling boy. His happy face is eerily projected onto a white cloth, wrapped around the head of a child, like a bandage that acts as a hovering projection screen. The black shadow of the boy looms inside the room like a ghost, it wiggles in little spasms. There is another image projected onto the wall behind the boy, of a tree on a path, and there is an open door right where the trunk of the tree would have been, framing a rear projection that shows slides changing in staccato rhythm: of grass, leaves, and flowers. On the soundtrack, crickets are chirping amidst the cacophonous noise of a city. Is that the sound of drumming rain, or is there a river nearby?

This shot has an uncanny quality, like an iteration of a strange dream. There is mystery in the nearness of the boy, who is the artist's son, the child-ghost spooking the animation studio, and in the face that seems to be peeling off his shadow. Ito eloquently creates the illusion of antagonistic temporal simultanieties within one filmic frame: stillness (the path in the background), slow motion (the smiling face), time-lapse (the shadow of the boy), and a rapid succession of single frames (grass, leaves and flowers in the door-frame). The juxtaposition of different temporal modes is at once the enunciation of an idiosyncratic film language, an allegory about the experience of "duration," as well as the creation of a bedeviling vignette.

The Moon (1994) displays some of the artistic themes that Ito dealt with in his early work. Elements of the artist's workflow are shown: the animation stand, drafts of the carefully scripted storyboard, the intervalometer, the photographing and re-photographing of pictures and projected images. Piled-up photos are featured, arranged, re-arranged, and animated. The cinematic process is as much the subject matter as the subversion and collapse of the laws of time, space, and perspective.

Shadows of the artist at work are visible. And although his appearance is brief, it exemplifies the way in which Ito always seems to insert himself into most of his early work: Like in December Hide-and-Go-Seek (1993), that uses footage that his son videotaped of his father. Like in Venus (1990), where a shadow of the artist taking photos is seen from certain angles. Like in Grim (1985), where he places his hand in front of the camera, underscoring the subjective point-of-view. Like in Spacy (1981), where the artist is visible in the final shot, camera raised to his eye.

Floating images in mid-air

Shadows, apparitions, faceless faces, devils, phantoms, and mummies seem to recur throughout Ito's filmography like a red thread. The supernatural theme takes centerstage in The Ghost, a short animation Ito made in 1984.

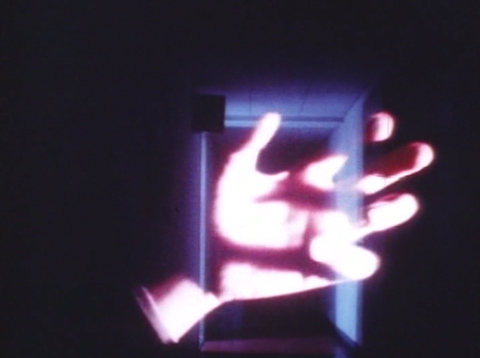

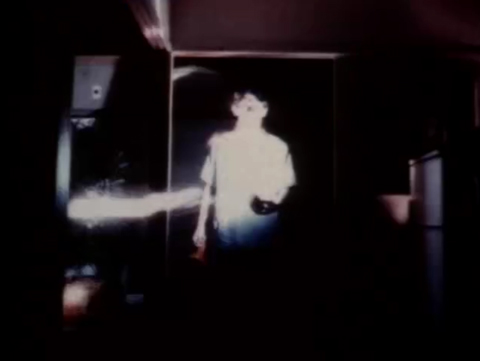

The setting of the film is a company dorm in an urban environment. Everyone seems to be asleep. The subjective camera moves restlessly through the empty halls of the dorm, submerged in red light, not unlike the lighting inside a darkroom. It scans every corner of the building: the foyer with shoe lockers, the common area, the laundry room, the basement, and endless halls. Strobing flashes are everywhere, denoting strange sources of energy, circles of light dart across the space. This place is clearly haunted, and as Yosuke Inagaki's soundtrack descends into a nightmarish ambience, we finally get to see the main protagonist of the movie, the ghost. His face is indiscernible because he violently nods his head, features lost in motion blur. Translucent images show up, of a hand closing into a fist and opening again, as if to check if the sensory system is still intact. The perspective seems to oscillate between the point-of-view of the ghost, and an outside perspective that looks for it.

Amidst the visceral expedition through the corridors of the dorm, shadows of the artist keep re-appearing. He is hardly perceptible, yet he is there, flitting through the frame, holding up boards that act as screens for the "floating images in mid-air,"[1] and shining a flashlight onto his protagonist, the ghost. Again, we see the artist at work. The entire 6-minute film is shot frame-by-frame, with long exposures. That's hundreds of photographs, and no doubt many sleep-deprived nights of meticulous work.

Right after the introductory sequences, there's a view out of a window, from within the building. After a camera pan, we see that it is the room of the artist, filled with monitors, viewers, videotapes, and video-decks. This beginning of the film mirrors the intersection where the working day ends and the working night begins: reflecting the double life Ito had at that time, of having a day job to support himself financially, and his night time work as an artist. Boundaries between work and free time blur. The personal is consumed by work, becoming a shadow of the artist, and the artistic process in itself becomes madness, a shadow of his daytime job. There is a clock that re-appears towards the end of the film, it's almost five in the morning. This indicates both the narrative time as well as the end of production time; Ito would have gone to sleep around dawn to get his two hours of rest, before going back to his day job. Ito's existential experience feeds into the self-reflexive representation of the production, and is another component in which the personal converges with the artistic expression.

Film as a way of articulating the self

According to Ito, watching Toshio Matsumoto's seminal Atman (1975) was a pivotal moment in his early student life, after which he knew that he wanted to make that type of experimental work. Ito recollects: "Looking at this film, I thought that everybody has a mystery that is hidden in some deep part of one's heart, and the act of personally finding out what that is, the act of wanting to know who you are by means of that, perhaps is what we call expression."[2] This epiphany stimulated most of the work he made in the 80s and 90s: finding different ways of delving into the self, and giving voice to mystic inner worlds.

I imagine that Ito studied Atman in great detail, and spent much time reconstructing the technique of sequential photography that Matsumoto used; to be able to recreate it, excel at it, and take the artistic language to another level. Ito said that Matsumoto — one of the pioneers of Japanese avant-garde film who was his professor in the 1970s — challenged him to realize Spacy, after Ito presented him with the production plans. Ito promised to himself to impress his master, who so deeply impressed him.[3]

Atman centers around a figure, shot in single frames from hundreds of different camera positions. Utilizing sequential photography that zooms in and out in rapid clockwise (and counter-clockwise) succession, the visual effect is vertiginous. The figure is sitting on a stool in an open landscape, wearing kimono and a Hannya mask, from Noh theater. This horned female demon appears in many famous ghost stories and stands for jealousy, malice, and madness. Her face is demonic, but also extremely sorrowful and disfigured by torment. Atman in Buddhism stands for "self." Considering the significance of the featured iconography in Matsumoto's piece, the key subjects "ghost," "madness," "mask," "photography" and "self" seemed to become founding elements for many of Ito's works that explore a complexity of human emotions.

In-between photographs of photographs

Spacy, is that film that Ito constructed entirely by using sequential photography, integrating sequences within sequences, and capturing images of a space within that same space: an empty school gymnasium.

The English adjective "spacy" describes a state of mind of someone not completely conscious of what is happening around them (often because of taking drugs or needing to sleep). The word could refer to the spectator's physical response while watching the film, it could be a subjective feeling Ito wanted to express, but it also contains another word "space" within it, which literally and figuratively is the subject matter of the film. One possible translation of "space" into Japanese is ![]() , a Kanji that can be read ken, (architectural: interval, space between pillars, length unit: about 1.8 meters), aida (space, interval, between, during, meanwhile) or ma (space, interval, timing). As a compound, the Kanji is used in the words

, a Kanji that can be read ken, (architectural: interval, space between pillars, length unit: about 1.8 meters), aida (space, interval, between, during, meanwhile) or ma (space, interval, timing). As a compound, the Kanji is used in the words ![]() (ningen: man, person, human being), or

(ningen: man, person, human being), or ![]() (jikan: time). Derived terms include:

(jikan: time). Derived terms include: ![]() (kono aida: the other day, recently, lately) and

(kono aida: the other day, recently, lately) and ![]() (aidaju: throughout, during).

(aidaju: throughout, during).

Interval, length, unit, space, distance, while, between, during, timing, man, person, gap, time, pause, recent, lately, throughout, viewer, interior. All of these words could be used to describe the film. But in a way, the film is also about all of the above words, and the relational shifts between the individual signifiers.

The first image in Spacy is that of a wall of windows, a single photograph that's followed by black film leader. The next shot is a different angle of the same windows, again followed by black. The camera pans around the ceiling in counter-clockwise motion. The intervals between the photographs shorten, speeding up the frequency that the camera scans the dimensions of the space. As the looping electronic music accelerates, the camera changes its perspective, panning around the gymnasium at ground level. Several tall photo easels are visible, arranged in a circle around the camera. The camera zooms into the first photograph. As it fills out the frame, it reveals the same space the camera just zoomed into, thus throwing the spectator back into the initial position. "Spacy consists of 700 continuous still photographs which are re-photographed frame by frame according to a strict rule where movements go from rectilinear motion to circular and parabolic motion, then from horizontal to vertical."[4]

Fixed framing, flicker effect, loop printing, re-photography—Spacy has many of the characteristics of "structural film." But Spacy seems to be more than a film about film, or in strict sense photography on photography. Like in "structural film, the in/film (not in/frame) and film/viewer material relations, and the relations of the film's structure, are primary to any representational content."[5]

But there is a psychological component. There is pathos that develops throughout the film, mainly owing to the intense soundtrack by Inagaki. If Spacy were a silent film, then one would surely have a very different experience. The soundtrack has the power to draw the viewer into a trippy nightmare; it is as if by some wicked circumstance, one could not escape the room. The spacious gym depicted in the photographs becomes a claustrophobic trap. In a way, the camera perspective could be experienced as a subjective point-of-view. The photos, frames within frames, are like windows, like doors; one always hopes to find a way out, to see what's beyond. But each time the camera perspective approaches what could be some type of opening, one is thrown back to the center of the gym. The logic of this cinematic illusion defines a system one can't break out of.

The trilateral relationship between the artist, the real world, and film[6]

For the most part, Ito uses photographs of his immediate environment and takes his inspiration from his daily life. He does not use found footage or any other sort of pre-existing material. He carefully constructs and chooses the images that he uses, that depict his living space, the surroundings of his residence, his wife and his child. Even some of the pieces that center solely on architectural spaces become carriers for psychic worlds, elaborating affective commentaries on the represented reality.

Though Ito's films are not political, it may be interesting to consider the socio-political context of Ito's practice. Most of his early work is grounded in the 80s, before and during the period called the "Bubble" (short for "bubble economy"). Japanese society was under a very rigid regime, dedicated to economic growth that accelerated at an unprecedented rate. It had huge trade surpluses and was striving to establish itself as the world's top economic superpower. The prime minister at that time, Yasuhiro Nakasone, was known for reforming the education system, and for "casting off the negative legacies of postwar policies." Nakasone was a conservative nativist who referred to Japan as a "homogeneous nation" with "one ethnicity, one state and one language," and he may as well have added "one goal."

Within this unbending system that exclusively focused on economic growth, there was little to no flexibility for alternative life models. A single subject had few choices but to submit to the "spectre" of Capitalism and to sacrifice for the larger good. The 80s are remembered as a time when everything revolved around money, capital, and ways to achieve personal and national wealth. At the height of the Bubble, it was said that the value of the property in Japan, a country smaller than the state of California, exceeded the monetary value of all the property in the entire United States.

But what did all this mean to children growing up in that era? What did it mean to adults who surrendered themselves to vicious cycles of societal demands, pressure, and work?

Watching Ito's structural films that use architecture to express the 'self,' I can't help but see imploding visions, fractured halls of mirrors of that time, and interpret them as manifest commentary on Japanese urban life in the 80s.

Like in The Mummy's Dream (1989), Ito strips life and surface beauty away from Tokyo. The film shows empty streets and seemingly deserted buildings within one of the most densely populated cities of the world. In the beginning, negative spaces between buildings and bridges are seen. By means of solarization and rattling image destabilization, the buildings seem to shake, as if shocked by some kind of inexplicable force. The camera zooms into vast spaces only to visually smash into architecture with vehemence, like a battering ram, crashing into corners, pillars, walls, and rocks. As if it was trying to open a hole into the surface, as if to dig beyond, as if to awaken some other spirit, dormant and lurking beneath layers of reality. Perhaps this subdued allegory is about some being from the past, a mummy. Perhaps this mummy has fears of a present that revolves around property—a present repressing deeper meanings in life.

Ito's spectres can be read as elements that go beyond being mystical figures. They connect the inside and the outside (using architectural spaces to express personal feelings), relate a present to a past (ghosts pointing to a life that is no more), and position the self within a larger world. They are a means to open up critical perspectives that public, verbal conversations do not tolerate, translating personal experiences within a closed society.

◊

This essay was written for the Injerto symposium reader "Language Constellations," published within the framework of Ambulante Film Festival 2011, Mexico.

Notes

[1] "Ghost." Synospis of the film. Takashi Ito. 1984, 6min., 16mm, color.

[2] Takashi Ito in the Holland Animation Film Festival Catalog, 2002

[3] Takashi Ito's autobiographical essay on Image Forum's website.

[4] "The Ecstasy of Auto-machines" by Norio Nishijima. Online article.

[5] Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film. Part One of Peter Gidal's introductory essay to the "Structural Film Anthology," published by the British Film Institute in 1976. Available online at http://www.luxonline.org.uk/articles/theory_and_definition%281%29.html

[6] Toshio Matsumoto in "Documentarists of Japan #9" by Aaron Gerow. Online interview.