Good Bad Investigatrix of Your Techsploitative Monsters

24 Sep 2011

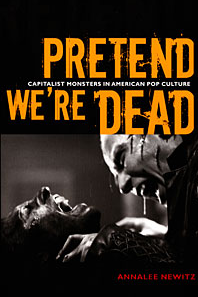

Spooky stories--like those examined in Annalee Newitz' Pretend We're Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture, Duke University Press, 2006 (ISBN 0-8223-3745-2, ppbk) http://www.dukeupress.edu

---have haunted America since the late nineteenth century, when "humans turned into monsters by capitalism", were made deformed and destructive.

I. Destroy All Monsters

Newitz' intriguing scholarship finds examples in novels: Caleb Carr's The Alchemist and Stephen Crane's Red Badge of Courage: the latter with its descriptions of dead soldiers influenced by Matthew Brady photographs. Gender relations are transparent in hyper-visual splatter films like Silence of the Lambs to television's CSI. She discusses serial killer Ted Bundy and the professionalism of his biographer Ann Rule, as well as the differing personas of child-killers John Wayne Gacy and Jeffrey Dahmer, and how Henry Lee Lucas relished sex with victim's bodies.

As one example of a social monster, she cites Norman Mailer's 1950s designation of the "white negro" (though not his murderer-hero of novel An American Dream), and especially Mailer's portrait of serial killer Gary Gilmore in Executioner's Song. Gilmore was an evocative figure to this reviewer in 1977, with TIME printing the killer's sexy pencil portrait of his girlfriend Nicole in her halter top, cutoff shorts and Dr. Scholl's sandals. Gilmore's brother Mikal has examined his own attraction-repulsion towards Gary in Rolling Stone magazine. Newitz contrasts Patricia Cornwell's serial killer novels with Bret Easton Ellis' American Psycho and Dennis Cooper's Trisk, both inhabiting a world of business capitalized with what Karl Marx called "dead labor". I am reminded how the genuine homicidal mayhem around 1970 of the southeastern Michigan "coed killer" John Norman Collins often became confused in the public mind with the radical rhetoric of White Panther Party hippies. More recently, media representations of the post-9/11 anti-terrorism pursuit, including the hunt for John Muhammed and John Lee Malvo in Virginia in 2002 (and, one might add, Jared Lee Loughner in 2011 for the shooting of an Arizona congresswoman and Judge), show the official slippage between groups and individuals in "terrorist" definition.

More recently, media representations of the post-9/11 anti-terrorism pursuit, including the hunt for John Muhammed and John Lee Malvo in Virginia in 2002 (and, one might add, Jared Lee Loughner in 2011 for the shooting of an Arizona congresswoman and Judge), show the official slippage between groups and individuals in "terrorist" definition.

Just as Newitz skillfully once dissected the post-graduate job market in a paper entitled "Growing up MLA"in 1998 at the Modern Language Association conference,where she faced the competition of other newly-minted Ph.D.'s in a boxy man's suit (the hiring committees didn't get it), the book's chapter on labor relations deforming hardworking individuals into monsters is where she is most convincing. The villainous Dr. Octopus in Spiderman, consumed by "symbolic-analytic services", illustrates Georg Luckacs' 1922 theory of reification, where mental labor is exchanged for salary. She applies her UC Berkeley-honed skills to Frank Norris' novel McTeague, where a de-professionalized dentist goes into gold mining, illustrates prevalent Social Darwinism in San Francisco a century ago.

[Photo courtesy Annalee Newitz]

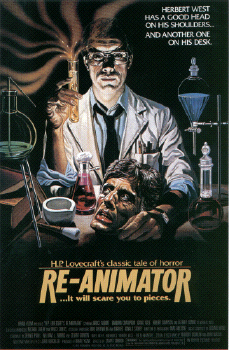

Another novel, Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson was written on the professionalism of the craft medicine in the 1880s, also the era when Allopaths won out over Homeopaths at various American University Colleges of Medicine. In both Stevenson's novel and subsequent film versions, including female versions of Jekyll after the 1970s, we see medical doctors gone mad in the pursuit of status and profit. Class relations gradually shift, with Jekyll middle class in the novel, but an upper-class decadent in the 1920 John Barrymore version. He is given a "dusky pallor in the 1931 and 1941 versions, where there are hints of sexual pleasures of his beastly condition. Similarly, "Donovan's Brain" is a clear representation of capital controlling science. Newitz describes physicians' professional proletarianization in these movies, yet resists an inviting and appropriate dig against the HMOs of today. She identifies Taylorism in ReAnimator, the human brain treated as one part in a factory process. Movies like ReAnimator, Frankenhooker, Pi, and Beautiful Mind are so inherently pessimistic in the face of economic oppression, they offer up self-destruction as the only possible means of revolt. "Perhaps", Newitz pines, "One day, our monster stories will not express the grief of a nation whose people pretend to be dead in order to live."

"Perhaps", Newitz pines, "One day, our monster stories will not express the grief of a nation whose people pretend to be dead in order to live."

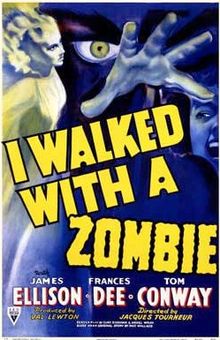

In turning over the undead, she mentions the Bela Lugosi groaner White Zombie. Few zombie movies are mentioned, not even the 1941 King of the Zombies, where Mantan Moreland organizes and (it being WWII)drills a squad of them. She cites Jacques Tourneur's I Walked With a Zombie but not Roky Erickson's psychedelic Punk rock song of that title, based on the classic "dead teenager" riff, and famously covered by REM on a benefit anthology CD for that troubled Texas songwriter. Nor does she mention Michael Jackson's zombie-dance extravaganza and albumn, Thriller, an odd omission for a pop culturista like Newitz. She could also easily have chosen to riff upon Mr. Jackson---the late, great infotainment monster himself---inserting commentary when noting the racism inherent in H.P. Lovecraft's constant evocation of the unspeakable and ghastly.

Her discussion of Birth of a Nation was probably crafted before DJ Spooky's 2004 re-cutting and anti-racist reframing of D.W. Griffith's pro-Klan 1915 movie. Like the industrialist's bleeding-heart daughter in Fritz Lang's Metropolis (soon turned into a 'robotnik' herself), the chapter on robots reveals Newitz's own distance from factory labor. She explores the love and longing of the little boy 'android' in Steven Spielberg's A.I. yet--as if saving sex for dessert--gives short shrift to oily Rudolph Valentino look-alike 'Gigolo Joe' and she cites the original novel on which the movie is based, written by David Gerrold, also writer of The Trouble with Tribbles episode of the original Star Trek TV show where the cuddliest of creatures proved destructive. She also alludes to Cynthia Brazeal and Rodney Brooks' constructions of 'emo-bots' in MIT computer labs and from affectionate cuddlebears, turns to robots equipped for sexual love. It is all well and good to examine the 'Romeo Pleasure Droid' in Circuitry Man,but where is mention of the early 1990s trope of 'teledildonics'? One can only suspect that Newitz's arrival at UC Berkeley a bit after the promising moment of Northern California cyberpunk, too late to drink the optimistically techno erotic Kool-Aid offered by the well-heeled eccentrics publishing MONDO 2000 magazine in the Berkeley Hills. may have had something to do with it.

The fifth section and final section of the book is on monsters of the culture industry itself. She moves from Nathanael West's novelDay of the Locust, which presents proletarians as monsters, to Mike Davis' nonfiction Ecology of Fear, an environmental study which might be read as the latest literature for a long tradition of Californian monster movies.Logan's Run and Network, both released in the US Bicentennial year 1976, foreshadow O.J. Simpson's white Bronco high speed chase a decade and a half later. Videodrome presented a Marshall McLuhan-like Canadian media analyst as villain, but Newitz doesn't explore it. Movies that examine fame, like A Face in the Crowd,All About Eve, and Sunset Boulevard, invite her to address the Frankfurt School intellectuals' bias against mass culture. Nurse Betty,Pleasantville, The Truman Show, Scream are best read using Antonio Gramsci's audience reception theory and class warfare in the ideological realm.And where is Situationist polemic to help her chew through the Spectacle?

II. It's Alive! Alive!

Pretend Your Dead has all the substance one might expect from a Berkeley PhD and a hard hitting, self-made critical journalist. We've seen her move through co-founding, writing and helping edit Bad Subjects, the oldest continuously publishing political and cultural project on the Web, and a few years after that, co-organizing with Matt Wray the tragically misunderstood Berkeley conference on Whiteness and co-editing their fine anthology White Trash.She promulgated online narratives of sexual adventure, and wrote the "Techsploitation" column throughout the Web boom. In this decade, she had a chip planted in her own body for a WiRED magazine story because she could, then moved on to a console in the command center of the crackling-with-energy scientific and science fiction website io9.com.

What drew me to the project most was its anti-dogmatic bent, and the fact that we wanted to inspire hope in people about the possibility of a more just future for human beings. I saw very little hope in the people around me who claimed they wanted a better world.

Newitz has long been a strong woman's voice among voices in what was too often a ludicrous, seamy, and posturing white-boys only world of technology. Newitz's investigations might look to Susan Sontag, champion of human rights, or follow more closely the heady outrage of Hannah Arendt, thus gaining more tooth. Yet what Newitz said to the Bay Guardian in 1996 about Bad Subjects applies to all her projects: "What drew me to the project most was its anti-dogmatic bent, and the fact that we wanted to inspire hope in people about the possibility of a more just future for human beings. I saw very little hope in the people around me who claimed they wanted a better world."

III. Famous Monsters of Twentyelevenland

Our psychic graveyards have more recently been populated with passionate teenage vampires, zombie Jane Austen novels and urban zombie pub-crawls partaken to the tunes of the beguiling Lady Monster that holds us gaga. Despite the Republican swarm's supporting cast of scary moms like Sarah Palin and Michele Bachman, its corporate-directed army of anti-union Governors and venal Washington tax-cutters and Chamber of Commerce shills, it's difficult to imagine cinematic imagery appropriate to portray the woes following the bursting economic bubbles of the endless late Bush era (and, as I write this in July 2011, a risk of national debt default). These horrors are potentially as cataclysmic to the US economy and its peoples, as the Fukushima tsunami and nuclear toxicity have been to Japan, though manifested in slow-mo eradication of the quality of oppressed American's daily lives, hopes and communities.

Imaginary battling giant monsters, made up of the godzillian tetrabytes of data, can be cheered on however, as it shapes itself into the democratic promise demonstrated by Wikileaks, the Egyptian and other middle eastern users of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, to take down or properly humiliate oppressive or invasive states...or to echo or emulates the pathetic, doddering and tottering international media giant Rupert Murdoch as he expresses crocodile-tear outrage at his own newsgatherers.

In a July, 2006 "Techsploitation" column, Newitz cited the villainous British East India Company in the Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest as accurately representing contemporary "Halliburton-size evil" in its pursuit of Captain Jack's magic compass, "the perfect colonizing tool" always pointed at desired riches. Then she plugged Pretend We are Dead, in whose academic pursuit she learned to "excavate the cultural meaning of real-life technologies by analyzing movies about imaginary ones".

...I say that until we understand the monsters in our dreams, we'll never defeat the ones who run the world.

Annalee Newitz is becoming the Sarah Connor of popular criticism, outrunning the life-killing Terminators of pop culture. Her closing paragraph reminds us: "There will always be people who want to consume their electronic toys and mass media without having to think about what they mean. Sometimes they'll even claim that there are no politics of science fiction--or science--because politics only takes place in Congress or at the United Nations. But I say that until we understand the monsters in our dreams, we'll never defeat the ones who run the world."

*Mike Mosher is Professor of Art/Communication & Digital Media at Saginaw Valley State University in Michigan. He has been a member of the Bad Subjects editorial team since 1995. Email: mosher@svsu.edu