Perceptions of the Infinite:

Moving into Dream Spaces of Reality with Kathy Acker

24 Sep 2011

[Still from Takahito Nakagura's Tatlin's Tower, USA 1999, 3'12"]

[Still from Takahito Nakagura's Tatlin's Tower, USA 1999, 3'12"]

KATHY ACKER'S TEXT RUSSIAN CONSTRUCTIVISM, ORIGINALLY part of her dream-novel Don Quixote reprinted in Blasted Allegories and Bodies of Work, is a text where myriad conceptions and ideas that relate to her method of art-making (plagiarism, cut-ups, appropriation) co-exist with her position as a female artist and writer living and existing in her own right in the world. In this text certain themes come up in various literary forms and genres, in particular, displacement and love, and also how displacement, or the way she is moving through or experiencing space or place, affects Acker's conceptions of love and relationships.

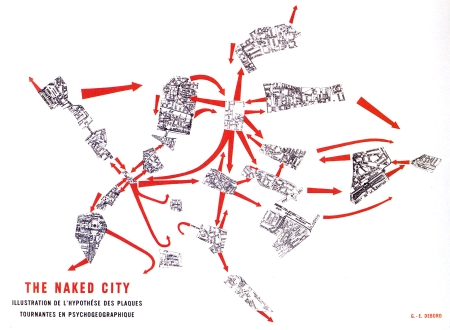

It brings to mind films such as Hiroshima Mon Amour and Alphaville, and the ideas of the Situationists (whom, of course, Acker was influenced by), all of which present utopian imagining for a city or environment where dreams or love and poetry are possible.

One way of reading Russian Constructivism is as a kind of journey or set of interactions between Acker and some of her lovers within a number of a different cities and environments, some real, some imagined, most centering on St. Petersburg. It brings to mind films such as Hiroshima Mon Amour and Alphaville, and the ideas of the Situationist International (whom, of course, Acker was influenced by), all of which present utopian imagining for a city or environment where dreams or love and poetry are possible. These imaginings are also often countered by dystopian environments, or cities that have been subject to some kind of massive trauma, and which have deeply and negatively affected the capacity for two people to love each other within a romantic relationship. Perhaps in spirit closer to the Situationists, Acker's poetry, which appears in a number of images, and as poems and in translations, transforms the hurt and pain that she writes about in regard to relationships and the spaces in which she lives. The changes brought about through her way of writing and art-making emphasize her feminist, anarchist and punk rock stance, which, of course, later inspired countless other female writers and artists. Realizing that this Acker text originally appeared in Don Quixote which was a dream, an avant-garde, plagiaristic appropriation of a classical text and its hero on feminist terms, further highlights the strong and radical impulse in the work to transform her reality through her writing.

Recognition: I'm really hurting. One of this hurt's preconditions is I'm in love with you. A city in which we can live. What're the materials of this city. (Acker 1997 p. 112; all page numbers of quotations in text refer to Bodies of Work)

The two "real" relationships Acker writes about, or in two letters she addresses to one of her lovers included in the text, are both heterosexual, and seem to be ones where alongside the passionate emotions and feelings of most romantic relationships, economic concerns come into play, presumably because of a shared living situation. Both relationships end disastrously, in linear time anyway.

It's not possible I can feel again after a winter and spring of no sexual love then for the second time in five years I moved in with somebody. That failed violently forcibly. (Acker 1997, pp. 120-121)

In writing about or to her lovers, Acker repeatedly returns to and problematizes the concept of ownership. The text shows how notions of ownership, or economic transactions often subtly and insidiously infiltrate various institutions of love, such as marriage or living with someone in ways that are normally associated with activities like prostitution or even drug dealing. These transactions seem to be blocking passion, joy and the ability for the lovers to find 'a city in which [they] can live.' The relationships seem to be fueled and troubled by need, desperation, perhaps reaching into a form of madness; the speed with which she talks about her feelings sounds as much like a drug addict as a lover.

Meanwhile in the alleyways, Dear Peter, I can't stand living without you? (Acker 1997, p. 108)Sixteen hours until I see you again. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16. I can count 16, but you'll probably not want to see me. If I see you, I'll want you. If I don't see you, I'll die. I'm going nuts.(Acker 1997, pp. 108-109)

In addition there are several scenes where she writes against or at least in response to the intrusion of this "ownership" that is hurting her in these relationships. In one scene she is being thrown out of her house; in another she writes about her lover's wife. A reader cannot miss the kind of economic machinery, perhaps financial dependence on her lover or vice versa, having a safe place to live in, etc. that must be around in these kinds of exchanges. What also becomes apparent is that the implied economic transactions are only one aspect of the ownership that is being imposed on her. Historically the economic dependence that usually a female would have on a male created scenarios in which the male would have the ability to mentally and psychically colonize a dependent person's mind(again the parallels between the way Acker is talking about heterosexual love relationships and prostitution and drug dealing become apparent, as an underlying requirement of the partnerships is that one partner becomes dependent on someone else, and is far less powerful.)

"When Eddie was kicking me out of his house, I put a razor blade into my right wrist in order to stop Eddie from saying 'You don't know how to love. No man will ever love you.' The people who saved me from death're my friends. (Acker 1997, p. 123)

[in first letter to Peter] I don't know what I'm doing. You're the only life I've known in a very long time. How can I let go of life again? You're my day and night. Forget it, little baby, he's told you clearly he doesn't want to have sex with you and he only wants you so he can revenge himself on his wife 'cause she once left him for a richer man. You are my madness. Come in me, my madness, and since you've already taken me, I beg you with everything that is me to take me. I'm sold, but not yet enjoyed. (Acker 1997, p. 109)

Having been displaced from her home, or having been cast into a secondary love role because her lover is using her to revenge himself on a wife, she fights with an alert and urgent consciousness in her writing. It is recognition that the love and pleasure, and perhaps also madness she longs for in her relationships, and a space where she could enjoy this kind of love, is initially being actively taken away from her. For Acker, the mechanistic power principle or "ownership" into which some relationships fall, has nothing to do with enjoyment or love. Furthermore, she also invokes her friends as the people who saved her, rather than her lovers, suggesting that friendships transcend the boundaries that economic situations and psychic colonization are imposing on her in her romantic relationships. They are part of her survival.

Acker's writing reveals that she enjoyed a precarity of existence that wildly independent women have known, homelessness, and which has been the plight of many writers.

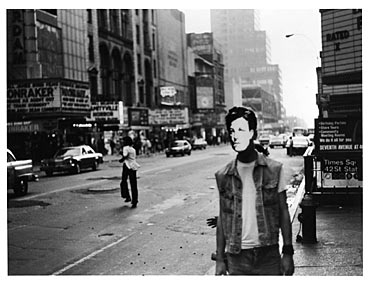

Acker's writing reveals that she enjoyed a precarity of existence that wildly independent women have known, homelessness, and which has been the plight of many writers. It is in this space of "homelessness" where her poetry and her movements or nomadism through her cities or her environments begin to take shape, and that love may begin to be possible. The images I'm concerned with, almost dotting the essay, are mysterious, and approach something strangely pure and surreal, even if the content of the images is often violent, hurtful and emotional. This might be the means or the mechanism by which her critique of ownership, and perhaps her critique of whatever problems or pain she is discussing, becomes as powerful, or visionary as the system of ownership that has dominated her love relationships as discussed earlier. The images could be viewed as a crux or compass through which readers can further access her writing. There's a quality to these images that is unusual, and they seem to describe her experiences of love and hate, but also in a broader vision, perhaps even 'psychogeographically' the VERY city-space she is living in.In Peter one morning, the female weightlifter fell out of her loft-bed. It was a beautiful day, late in September. Larks were singing and drops of sunlight were filtering through the navy blue Levelors (through the clouds through the pollution through the surrounding buildings' walls) which she hadn't opened since she bought them 'cause she didn't want to see junkies shooting up. A newspaper below her fallen body: CITY OF PASSION (Acker 1997, p. 108)

[Still from Hiroshima, Mon Amour]

Somewhat similar to Hiroshima Mon Amour and Alphaville, within images of Acker's text the city takes on a dream-like quality amidst the hurt or trauma or dystopian circumstances, places where her perceptions are almost floaty and contradictory, and the connections or trajectories between the various locations or markers are indirect and unspecified. (This kind of un-specificity is in direct contrast to other parts of her text which specifically mark locations, and the kinds of nightmare miseries that are being experienced in those places, particularly in St. Petersburg, and mirror far more closely her experiences of "ownership" in her relationships.)

In the weightlifter quote above, she is displaced from her bed and falls into a city called Peter, a fictional space, or perhaps standing in for St. Petersburg, or poetically linked to one of the names of her lovers. In this city, even if we're not sure exactly where it is or where she is after she falls(falling out of the loft bed could also be read as a metaphor for waking up), perceptions of her space are piled up in a list formation: "beautiful day, late September, larks singing, drops of sunlight, pollution, building walls, junkies shooting up, and a newspaper beneath her fallen body." Thus a seemingly awful event is transformed, not into something beautiful at all, but into a space where reality can be seen, and possibly experienced. Rather than dwelling within an imaginary non-state of being, like a mere 'kid' looking for home, or longing for security, Acker, the writer, becomes the poet once again. These kinds of indirect movements or poetic ways of experiencing her space continue in her narration; just after the above quote she writes 'Meanwhile, in the alleyways,' almost like a stagenote, as she begins her first letter to Peter. (Acker 1997, p.108). After the second letter to Peter, before beginning a brief allusion and historical anecdote about some early twentieth century avant-garde Russian/Soviet artists she writes 'Walking the streets.'(Acker 1997, p. 111). As readers we don't know which streets.

Rather than dwelling within an imaginary non-state of being, like a mere 'kid' looking for home, or longing for security, Acker, the writer, becomes the poet once again.

In the last section of the text, Russian Constructivism subtitled 'Deep Female Sexuality: Marriage or Time' which begins with the quote discussed above, 'When Eddie was kicking me out his house?' there is a slow, almost magical build-up of several surreal and strange images, leading to an intensely vivid description of sex and perhaps love. (Acker 1997, p. 123). Thus in this section time seems to move in reverse, and we see her moving away from hurt and pain into a homeless or displaced position, and begin to make the space she is dwelling or moving in hers. Also we do not know exactly who she is speaking to in these sequences.

[Still from 'The blue tape' by Kathy Acker and Alan Sondheim (1974)]

You said, 'Light light. Those who survive must learn mathematics.' For me there's just love, I'm scared of love. I run away from an immediacy. One of my legs is extending outwards. You're owning me. A sky of hot nude pearl until?crickets in these sheltered places?the wind ransacks the great planes. You are taking over control so I can relax. I'm alone on an island. I'm all by myself. (Acker 1997, p. 124)

She apparently has moved away from the dystopian city, into a more exotic locale, one that seems more like a dream, or perhaps another dream space that stands in for the city, in the same way as she calls her space "Peter" before. Here she seems to be able to create openings in her space, and perhaps the verb she uses "whirling" is somewhat akin to what the Situationists are referring to when they speak about 'drift' and the 'derìve'.

Here, I'm waiting for what is to follow my collapsed dreams. I'll be more precise: I'm waiting for you 'cause I can't know anything and everything's whirling. His hand put itself on top of the clitoris and pressed. It didn't move. Her own hand was resting on her clitoris. His hand pressed down, through her hand, on the clitoris. I'm alone again on this island. I've my books around me. I don't know why I feel lonely. (Acker 1997, p. 124)

Poetry becomes a means of movement and empowerment for the writer, a form of magic, and it is in this space,where she creates her own mobility through these images, and for the first time in the text joy or pleasure begin to be felt and seen; perhaps it is also possible to read some of these sequences as a parallel to Situationist ideas regarding play.

I remember waking up. First, I see your head. I see your eyes're open and you're looking at me. I have to smile because your obvious love for me makes me smile. (Acker 1997, p. 124)

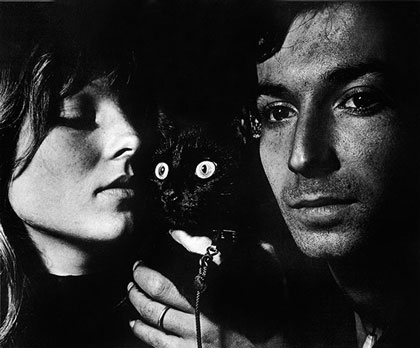

[Photo from the book Love on the Left Bank]

*

Tamara Browne lives in Madrid, Spain and has been interested in making connections between writing and film, both as a student and in projects outside of school. She wants to know what is writing's relationship to film and is interested in interdisciplinary art and literature, and bridging ideas that are often separated in time, such as ancient poetry and post-modern theory. She studied Classics at Pomona College and at the University of Chicago in an MA program, and film and video at the San Francisco Art Institute MFA program. She is currently writing an introduction for a Spanish translation of Acker's book Empire of the Senseless.