Got Beef with Culture:

Flesh-ing Out Semiotics with Jon Moritsugu

12 Sep 2012

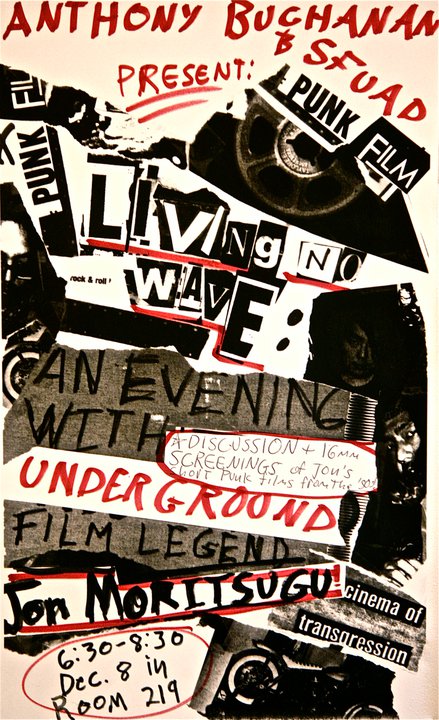

Note: Jon Moritsugu and Amy Davis appear in person at OTHER CINEMA on Saturday, September 22, 2012 to premiere their latest film, PIG DEATH MACHINE!

In the Fall of 2010, shortly after the shooting of his new cinematic venture

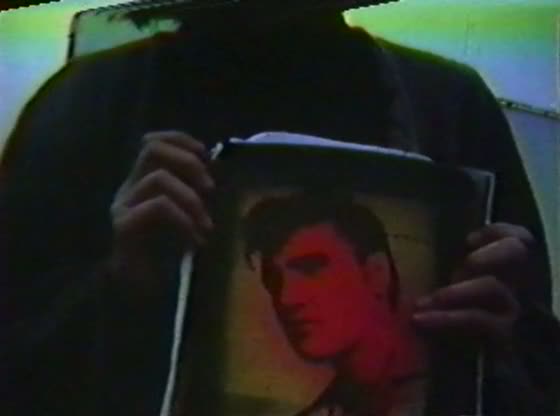

PIG DEATH MACHINE was completed, I held a public screening and interview with underground film auteur Jon Moritsugu, focusing on the early short films upon which his reputation was built. Frequently lumped into New York’s Cinema of Transgression, Moritsugu expresses graditude towards the movement’s founder, Nick Zedd, for providing him with screening opportunities, but maintains a discomfort for his historical categorization within the movement. After a discussion about this, we focused on Jon’s early masterpiece, DER ELVIS, (1987) an electrifying deconstruction of the biggest human commodity produced by the American media: Elvis Presley. Moritsugu’s equally beautiful and repulsive film, combining fuzzy images of meat, American commodity, and unflattering off-the-tube shots of The King, is a timeless anti-pop statement, as well as a structurally revolutionary film. Yet for all the film’s brilliant antagonism towards celebrity culture, Moritsugu to this day insists he maintains a “love/hate” relationship with The King. What follows is a highly condensed version of the discussion. His wife and leading actress, Amy Davis, was present and contributed occasional thoughts.

It was the week Elvis spoke from the grave, his ‘ghost seen by dozens.’ Down at the abandoned gas station on Ave. B, the spectral image of The King flickered over a sheet tacked up on a board. Thirty people had gathered to watch a program of No Way Normal films, the best and least normal of them breaking down the body politics of the fat ol’ sex god from Memphis. Jon Moritsugu’s DER ELVIS, in fact, showed how

He ain’t nuthin’ but a signifier.

—Cynthia Carr, Village Voice, “Learning to Love the Monster.” November 1987

Jon Moritsugu: With something like DER ELVIS...it’s not like I was trying to make Elvis look bad; I was trying to say something more about the culture that produced someone like Elvis Presley, and what he became later in life, when he was all overweight, doing his cheesy music, like, that’s a messed-up culture...

Anthony Buchanan: With DER ELVIS, part of the importance is the ambiguity: It does NOT seem like you’re tearing apart Elvis; you’re tearing apart the very idea of Elvis, because this film creates such a savage portrait, not only of Elvis, but of the inevitable mythology that [the] media created out of him... This is a film that was once called by J. Hoberman one of the top fifty films of the 1980s...

JM: Just one more thing, Anthony. You hit the nail on the head...I’d say one or two other critics in the whole history of this movie have actually said “whoever made this movie, we figured out that this person, as much as he hates Elvis, he loves Elvis,” and only a couple people have actually figured that out, and you sort of figured that out too...

With something like DER ELVIS, it’s not like I was trying to make Elvis look bad; I was trying to say something more about the culture that produced someone like Elvis Presley, and what he became later in life...—Jon Moritsugu

AB: The aspect that makes this kind of a convoluted discussion about whether or not we “hate” Elvis, or YOU hate Elvis, is...who...who is Elvis? Which Elvis are we talking about here? Is it this mythologized postmodern Elvis that he became as a result of media, or is it this individual...human being?

JM: It’s hard to say, it’s like Bruce Lee Hall of Mirrors, ya know, mirror upon mirror upon mirror; we don’t really know who we’re talking about. But I think when I made this I could draw upon my own experiences, just being a kid growing up in Hawaii, and like literally every two to three years it would be like “Elvis Presley Night” in a big concert hall, and it always just struck me as being sort of odd...

Audience member: Was that more your own interpretation of Elvis, or more of a perceived energy of what people think of when they think of Elvis, with all the whimsical, violent imagery?

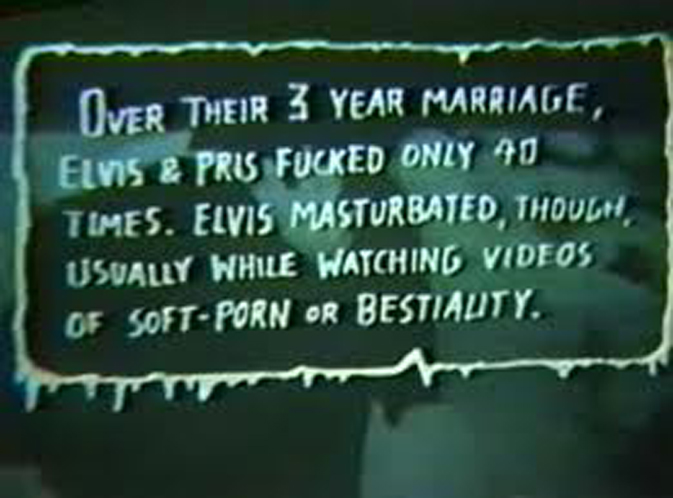

JM: When I started out I knew I wanted to make this movie about Elvis, I have a love/hate relationship with him, stuff I like, stuff I don’t like, but I actually did tons of research, and I was trying to base this all on fact. A lot of it’s heresay, his bodyguard printed a memoir... [A]ll that info on the screen is based on fact, interviews... I had an inkling about how I wanted the movie to look, and the more research I did, I thought, wow, this is supporting my thesis, that Elvis had these amazing magical qualities, he captured this energy of the early days of rock and roll when it was being invented. He also got majorly commodified and puppetted out and became this TV commercial by the end of his career. That was my theory...but I had to do research and see if the facts would support it.

Audience Member: I had a question about the juxtaposition you were doing with the meat—it’s the first time I’ve seen it, but were you trying to say how women—I guess men too—treated him like a piece of meat? Or, were you trying to say he was thrown around like a piece of meat?

JM: I think it’s all that and a lot more. Meat, it’s something that has to be fresh, it eventually goes bad and goes down the drain; maybe that’s the career of a performer, I don’t know...

AB: Because I’ve seen all your features up to this point, I think it’s safe to say the meat is obviously your primary semiotic, I think we can call it that. You use it in very different referential ways. What IS the meat? What does it signify?

JM: I just think it signifies what we all are, ultimately. I think it’s just a good metaphor for human beings, artists or anyone out there, entertainers... For my Elvis research, especially in the early days, there were a lot of people who were like, “Yeah, by the end of his career, he was treated like a piece of meat.” It was a common phrase used by a lot of these biographers. It sorta stuck in my mind, then I was like, “let’s just take this literally, and make an Elvis Presley movie where he's a prime rib, and I’ll animate it with Elvis songs,” then I was like "Naw, that’s too cutesy, I don’t wanna do that." I definitely took the meat thing literally, but also, I was playing a little “Cinema of Transgression”: I’m gonna throw some raw meat in your face. Also, I noticed how it was making people uncomfortable (during shooting); people were getting squeamish...and I decided that was a cool thing to use in my movies to get a response; people are gonna laugh, people are gonna get grossed out, but I think with meat there’s no middle ground.

AB: So that really is the origin? The combination of the Elvis references, and this...

AMY DAVIS: No, he’s fibbing. It was with MOMMY, MOMMY, WHERE’S MY BRAIN; the whole metaphor of commodity culture, it started with MOMMY MOMMY. A little bit of Fuck You to shock art, and then it’s been digging along.

JM: [inaudible] ...American economic system. We are all pieces of meat in this big...MACHINE!!! AHHH!! [laughs]

...people are gonna laugh, people are gonna get grossed out, but I think with meat there’s no middle ground.—Jon Moritsugu

Audience member: [About Todd Haynes, mostly inaudible]

JM: Yeah, Todd Haynes—For those of you who don't know Todd Haynes, he’s an independent filmmaker. He and I went to the same college; he was a few years ahead of me. You might know him for his Bob Dylan movie with the seven different actors, but Todd Haynes made a movie the same year that DER ELVIS came out, and it’s the Karen Carpenter story (SUPERSTAR). He made a documentary about them, but this is crazy...he used Barbie Dolls instead of actors, and one of the issues was that Karen Carpenter had anorexia, so in the movie, he was sanding down the Barbie Dolls, so they got skinnier and skinnier, and it’s actually really creepy man! [laughs] So he made this movie, but he grabbed all the music without getting permission from the Carpenters, and so he got busted. He can’t show the movie anymore, but for a long time, they were doing a lot of double-features in the film scene with DER ELVIS and the Karen Carpenter movie...

AD: Two great movies you’ve never seen! [Audience laughs]

AB: This is something you’ve become very renowned for, and it’s very admirable, particularly since SCUMROCK (2003): this relishing of the very primitive techniques, especially shooting off the screen, and the process of the resolution lines that appear. Was that something you kind of stumbled on, like the meat?

JM: Yeah, I think it was the movie before this where I realized that, aesthetically, I’m attracted to stuff that...other people might perceive as garbage, weird feedback noises, clanking sounds, static on the screen, and I also think it’s part of the whole filmmaking process. I am turned on by stuff that maybe is not precise, that’s staticky, that’s weird, off-beat, off-kilter...

I consider it [DER ELVIS] a New Wave documentary, um...almost like Michael Moore, where he’s discussing facts, stuff that’s going on in the government or whatever, but his personality is very much a part of the movie.—Jon Moritsugu

Audience Member: Jon, when you were making this Senior project, I assume there were other students in your class who were appropriating sounds. Were they saying “you can’t show this?” Because in other art forms, collage, appropriating...it’s okay, but in film, it’s a problem.

JM: That’s a good point, cuz before I started making this movie, I had an instructor, Leslie Thornton, who’s an experimental filmmaker. I had a meeting and I was discussing this Elvis movie I wanted to make, and I was like “There’s no way to escape his music. I have to use his music.” So I did some preliminary research, and his music is SO expensive, so I had another meeting where I said “I can’t afford this.” And so she finally sat me down and said “Hey, you’re beginning, right?” “Yeah, I’m learning this craft, I don’t know what I’m doing.” She said, “Why don’t you not worry about this legal issue right now? Use this project to become a better filmmaker, improve your editing...” So I took her advice, made the movie, and then lo-and-behold, it actually caught on in the world, and that’s when it got weird cuz I had to cancel a couple screenings cuz I was afraid I was gonna get busted. I was talking to Amy, and I realized that...I should have been prepared for more success. But, I counter the argument with-the reason the movie works so well is because I DID use Elvis’s music...there was no way for me to get it legally. So I had to take a chance and make my name with this one. Just like Todd Haynes; his movie wouldn’t have worked out if he didn’t use the Carpenter’s music; he took a chance, made the movie, and made his name. He can’t show it anymore, but now he has a name, so...

AB: I have one last question... Is this a documentary? Or is it something else?

JM: DER ELVIS? I-I think it’s like one of the first New Wave documentaries. Like today we have reality TV, like, “Wow, I’m following...” There’s a story but there isn’t, is it real, is it not? It’s blurred. I think this is an early example of someone taking the documentary methodology, and kind of turning it on its head. I consider it a New Wave documentary, um...almost like Michael Moore, where he’s discussing facts, stuff that’s going on in the government or whatever, but his personality is very much a part of the movie. That’s what I think my movie is.

The author, right, with Amy Davis and Jon Moritsugu

◊

Anthony Buchanan is a filmmaker and scholar of underground and experimental film. In addition to teaching Experimental Film and History of World Cinema at Santa Fe University, he has shown work in numerous New Mexico venues, as well as frequently providing visuals for local music shows. He has freelanced as a film critic for the Santa Fe Reporter and the Santa Fe New Mexican, as well as lecturing on topics such as the “History of the Occult in World Cinema,” and “Paracinema in Performance.” His forthcoming multi-genre essay film, I WILL BE CALLED LUCIFER, will be released in 2013.