The Blessing of Silence:

John Cage and Radio in the 1920s, Part 2

12 Sep 2012

Radical Silence: “Other People Think” (1928)

While attending Los Angeles High School, Cage, a high-achiever and class valedictorian, distinguished himself in oratory. In 1928 he represented his high school in a Southern California–wide contest and won first place for his speech, “Other People Think,” on the subject of US–Latin American relations. (1)

“Other People Think” was delivered at the Hollywood Bowl that same year and is the earliest of Cage’s writings to have been published. (2) The speech is worth examining closely, since it gives a window into Cage’s concerns (at 15!) around the time of his involvement in radio. Moreover, the social, political, and religious outlook on display in this speech remained at the center of Cage’s worldview in the 1930s and 1940s, and even later. Because both his music and his writings on music continue to be shaped by these concerns, Cage’s views on radio and, more broadly, on the significance of electronic technology to new music, ought always to be considered against this backdrop of social, political, and religious thought. Cage himself remained proud of this speech and cited it approvingly in later decades.

Cage begins his speech by describing how the United States has evolved from its colonial beginning into a world power with far-flung territories of its own. US influence, however, does not stop at its own borders. “She exerts a strong influence over Haiti, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Dominican Republic. She has circulated her dollar throughout the Latin American countries until she is spoken of as the ‘Giant of the North’ and thought of as the ‘Ruler of the American Continent.’ There is, ” Cage concludes “a Gulf of Misunderstanding between the Rulers and the Ruled of the American Continent.” (3) Cage devotes the rest of his speech to dissecting the political and economic causes of this “misunderstanding.” Most significant of all, in light of Cage’s later career, is the speech’s prescription of silence as a spiritual and political solution to international strife.

...Assuredly our posterity must not be slandered as the devotee of a Golden God. We must not follow in the ways of certain American Capitalists, for only when we cleanse our hands of gold-dust and share with the Latinos of this continent an unselfish handclasp will the sun of Pan-Americanism illuminate the horizon.—John Cage

Cage’s internationalism and utopian (future-directed) orientation may be discerned early on. The following remarks stress the need to acknowledge the present interdependence of nations as well as their future potential:

A short while later, Cage’s political radicalism asserts itself, when he denounces “certain citizens of the United States,” (5) capitalists, for having damaged US–Latin American relations. Cage writes:

...Assuredly our posterity must not be slandered as the

devotee of a Golden God. We must not follow in the ways of certain American Capitalists, for only when we cleanse our hands of gold-dust and share with the Latinos of this continent an unselfish handclasp will the sun of Pan-Americanism illuminate the horizon. (6) [emphasis added]Cage amplifies these comments by citing recent interventions in Bolivia. The villains are “American Capitalists”; those who dare to criticize are “radical minds”:

Is Latin America correct in calling our altruism masked imperialism? ...

What are we going to do? What ought we to do?

(7) [emphases added]To answer the question, “What ought we to do?” Cage imagines a quixotic, utopian solution: a period of silence should be imposed on the entire United States. Cage writes:

Cage’s remarkable fantasy can be interpreted in many ways. One possible reading is that against the depredations of American capitalism, Cage, like Quixote, has arrayed the power of imagination. On the other hand, perhaps it is a supernatural power that Cage invokes; the proposed silence is of a distinctly religious, even eschatological character. It is a “blessing,” enforced by some higher power that completely disrupts human activity, even the power to speak, as a necessary prelude to a transformed reality.

To answer the question, “What ought we to do?” Cage imagines a quixotic, utopian solution: a period of silence should be imposed on the entire United States.

Silence, in Cage’s fantasy, has both an outer and inner aspect. Although imposed from without, it is also humbly accepted and adopted by Americans, who would be “hushed and silent.” This “inner” silence resembles prayer; indeed, Cage has imagined his fellow Americans being forced to pray. This inner silence Cage understands to be the only basis for real communication, because only in silence will Americans be able to recognize the reality of the Other, the reality that Other People Think.

Cage’s sermon-like speech was delivered at the Hollywood Bowl in 1928. His radio show had already ended the previous year, but one wonders whether the young man would have wished to broadcast his sermon over the airwaves, if given the chance. Of course, it is doubtful that KNX or any other commercial radio station would have been interested in spreading the teenager’s gospel of prayerful anti-capitalism. Many years later, however, at the height of his fame, Cage did seek to broadcast such sentiments on the Canadian Broadcast Service. Commissioned by that organization to write a piece of music for the US bicentennial, he provided Lecture on the Weather (1975), a collage of Thoreau texts read by twelve speakers against a backdrop of wind, rain, and lightning effects. The work employs chance operations, except in its introductory section, a didactic Preface read by a single narrator. Cage’s Preface, one of his most explicit political statements, traces the adult composer’s preoccupation with silence back to his teenage speech “Other People Think.” Cage not only mentions the earlier speech by name, he also restates its political and religious argument and reaffirms his commitment to its message.

The desire for the best and the most effective in connection with the highest profits and the greatest power led to the fall of nations before us: Rome, Britain, Hitler’s Germany. Those were not chance operations. We would do well to give up the notion that we alone can keep the world in line, that only we can solve its problems.

More than anything else we need communion with everyone. Struggles for power have nothing to do with communion. Communion extends beyond borders: it is with one’s enemies also. Thoreau said: “The best communion men have is in silence.”

(10)

Source: Radio World 23 January 1926:17.

Silent Nights

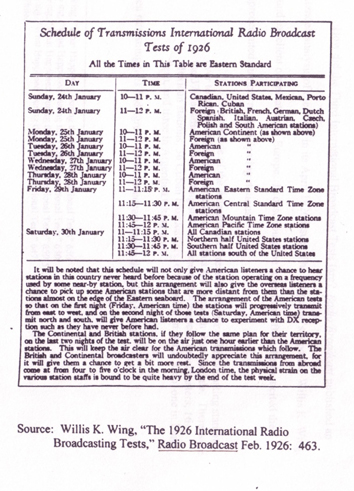

As Lecture on the Weather demonstrates, Cage’s vision of a silent America, first described in the 1928 speech “Other People Think,” continued to occupy a place in his outlook decades later. I now wish to raise the possibility that an actual historical event lay behind Cage’s trope of silence as the generator and guarantor of conscience and communication. This event was one that no one interested in radio or international news was likely to have missed. The event, advertised in newspapers and broadcast over radio the world over, was the Third International Broadcasting Tests of January 24–30, 1926. For the week of the Tests, virtually every radio station in the United States agreed to go silent for two-hour blocks each night, so that listeners might be able to receive programs being broadcast by designated foreign and domestic stations.

The origin and history of these tests are of interest in their own right. The three sets of International Broadcast Tests (1923, 1924, 1926) grew out of the American practice of “silent nights.” On silent nights, stations in designated areas would go off the air once a week, so that listeners could pull in stations from far away. The practice of “silent nights,” first suggested by the US Department of Commerce in 1922, had been adopted by Chicago radio stations in February 1923 and had spread quickly to other cities. (11) The immense popularity of national long-distance listening, or “DXing” as it was called led, by the year’s end, to attempts to create silent nights on an international scale.

The first International Radio Broadcast Tests were arranged for the week of November 25–December 1, 1923, as part of National Radio Week. Organized by the publisher F.N. Doubleday, America’s Radio Broadcast (owned by Doubleday) and London’s Wireless World and Radio Review, these broadcasts involved only designated English stations and American stations on the East Coast. To attract listeners to their transatlantic broadcasts, the sponsors engaged pioneering radio announcer Frank Conrad, as well as the international celebrities Henry Ford and Guglielmo Marconi (who spoke from England). The Tests met with only limited success, however, because organizers had neglected to secure the cooperation of Canadian, West Coast, and low-power stations, and the signals of these stations interfered with transatlantic reception. (12)

A Second International Radio Broadcast week, involving over 500 US stations and stations in England and Continental Europe (France, Belgium, Italy, Spain) took place in November 1924. When these Tests, like the previous year’s, did not live up to expectations, critics blamed programming conflicts, “bloopers” (caused by radiating receivers), and weak signal strength. Nevertheless, broadcasters were optimistic that better planning and newer, more powerful transmitters would overcome reception problems in the future. (13)

Radio broadcasters and enthusiasts also hoped that long-distance listening would promote a sense of “world citizenship” in listeners and would thereby help foster international peace and understanding.

The Third International Broadcast Tests, scheduled for January 24–30, 1926, took more than two years to organize and were by far the most ambitious attempt ever to involve the world in long-distance listening. European stations participating in the Tests included British, French, German, Austrian, Italian, Spanish, Czech, and Polish ones. (14) In North America, Canadian, Mexican and US stations participated, while in the Caribbean and South America, stations in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Peru, and Argentina took part. (15) Enormous publicity efforts were made to alert the public to the impending event. The prestige of the Tests had grown so much that sponsors now hoped to arrange for the King of England “to address a few words to President Coolidge while millions of us radio-eavesdrop.” In New York, an office was set up to furnish the press with daily and hourly updates, while radio magazines such as Radio Broadcasting and Radio World sought to engage listeners by offering to mail “verification cards” to those who submitted details of foreign programs correctly described.

For listeners, these tests promised the excitement of listening in on “exotic” foreign countries in Europe and Latin America. Radio Broadcast wrote:

Excitement, however, was not the only goal of participants in the International Tests. Radio broadcasters and enthusiasts also hoped that long-distance listening would promote a sense of “world citizenship” in listeners and would thereby help foster international peace and understanding. Captain Eckersley, chief engineer of the British Broadcasting Company, had this to say about the upcoming Third International Broadcast Tests:

Radio Broadcast’s staff seconded this view:

The hope of hearing faraway European stations was undoubtedly the chief attraction of the Third International Broadcast Tests for many in the United States. Indeed, the first five nights of the Tests, Sunday through Thursday, were devoted to transatlantic broadcasts; on those nights, from 11 p.m. till midnight, Europe broadcast to America. On the final two nights, Friday and Saturday, only stations in the Americas were allowed to broadcast.

Surprisingly, among American audiences, the most popular part of the Tests proved to be something that took place on the last two nights, namely, their institution of rolling silences that moved East to West and North to South on the American continent. (19) The rolling silence of the final night, Saturday January 30th, permitted citizens of the United States to listen appreciatively to the broadcasts of their Latin American neighbors. Radio Broadcast observes that, ordinarily, “stations in Mexico and South America are infrequently heard because stations here operate simultaneously on similar frequencies. During the silent period for American stations,” however, “the sonorous call of CZE of Mexico City was heard all over the United States, and the announcer at that station made many friends by his thoughtfulness in frequent announcements.” (20) Radio Broadcast concludes its analysis of the 1926 Tests with the recommendation tendered by many participants, that the practice of rolling silences be instituted nationally on a permanent basis. (21)

How did the Third International Broadcast Tests fare? Radio Broadcast published an extended analysis of the event in its April 1926 issue. The magazine’s reporter, Willis K. Wing, found excellent cooperation in Europe. In describing the American effort, he first cited the unprecedented number of participating stations:

Even rum smugglers had agreed not to broadcast during the silent hours. (23)

Unfortunately, however, this noble unanimity of purpose was broken by certain stations on the West coast. Radio Broadcast specifically singled out two stations for noncompliance: “The cooperation of the American broadcasting stations was practically complete with the exception of several of the California stations, notably KNX at Hollywood and KFI at Los Angeles.” (24) Radio Broadcast implied that the California stations’ reasons for not keeping silent were dishonest and simply a fig leaf for naked greed. “The operators of KFI,” Willis Wing sarcastically reported, “felt their individuality would be greatly limited by participation,” and, moreover, “the chances of California listeners for hearing foreign broadcasting was very slim, and to that was added the confession that theirs was in part a commercial station devoted to selling time on the air, and that they saw no reason for making any financial sacrifice.” (25) Radio Broadcast lets a letter to the editor have the last word:

Although the exact dates of Cage’s employment at KNX are unknown, it is nearly certain that Cage was working at KNX during 1926, if not in January when the Tests occurred, then certainly in the spring, when magazines such as Radio Broadcast offered their post-mortem on the Tests. Most probably, Cage was at KNX throughout the entire year. (27) The block of hours that KNX and other West Coast stations had been expected to keep silent, 7–9 p.m., would have begun only an hour or two after Cage’s Boy Scout show, had KNX cooperated. However, even if future research determines that Cage’s radio show did not begin until after January 1926, it is most unlikely, given his family’s involvement with radio and his own internationalist sympathies, that Cage had been unaware of the Tests.

[O]ne might argue that Cage’s involvement in radio played a role in his developing the powerful and prophetic metaphor of America the Silent.

The rolling silent hour (8–9 p.m.) of January 30th that had allowed United States citizens to hear their Latin American neighbors is, essentially, what Cage proposed two years later in his speech “Other People Think.” Moreover, like other radio idealists, Cage hoped that the institution of silence would foster a new era of international communication, good feeling, peace and prosperity for all.

“Other People Think” was just one of several speeches that Cage gave, while in high school, on the subject of “international patriotism.” In a 1985 interview with William Duckworth, Cage reminisced, “My valedictorian speech was on international patriotism, the devotion to the whole world, which I was not taught in school. I was taught only the patriotism part—swear allegiance to the American flag—and I was saying we must swear allegiance to the whole world, which no one taught me in school.” (28) Could the era’s radio magazines and the internationalist rhetoric that accompanied the annual Tests have been among the sources of his ardent internationalism? Of course, in the aftermath of WWI, internationalism seemed to many people necessary to prevent such a horror from ever happening again.

In sum, one might argue that Cage’s involvement in radio played a role in his developing the powerful and prophetic metaphor of America the Silent. At the very least, his involvement with radio could only have reinforced his internationalist ethos. Moreover, the negative publicity accorded to KNX’s desecration of silence may have suggested to him a concrete example of American capitalism’s willingness, in the pursuit of profit, to disrupt vital communication with one’s neighbors. American capitalism, he must have felt, “needs to shut up.” (29)

Cage’s involvement with both radio and silence would continue in later decades. Indeed, Cage restages the act of silencing one’s radio in his 1956 Radio Music. This composition, “for 1 to 8 performers, each at one radio,” requires each performer to silence his or her radio at multiple points throughout the work’s six-minute duration. As each radio falls silent, the sounds of the other radios, and of the environment, can be heard more distinctly. When all the radios are finally silenced at the piece’s end, audiences and performers alike may find that they want to continue listening to each other.

◊

John Smalley holds an M.Phil. in Historical Musicology from Columbia University and has performed as vocal soloist throughout the Bay Area. In 2009, he was awarded a prestigious Shenson Performing Arts Fellowship. He regularly lectures on music and cinema and is the founder of Radical Visions Cinema Club, a 400-member organization devoted to viewing foreign and experimental films.

Notes

(1) Hines 77.

(2) “Other People Think” was first published in Kostelanetz’s anthology John Cage (1970) with a prefatory note stating, incorrectly, that it “was presented in 1927 at the Hollywood Bowl.” As is often the case with Cage’s published speeches and lectures, the presentation date given is one or two years too early. Information given in the speech’s twelfth paragraph (quoted on page 17 of this essay) indicates that Other People Think was, in reality, delivered in 1928: “Six years ago, three American Banking Companies loaned 26 million dollars...According to this contract of 1922?”

(3) Kostelanetz 45.

(4) Kostelanetz 45–46.

(5) Kostelanetz 46–47.

(6) Kostelanetz 46–49.

(7) Kostelanetz 47–48.

(8) Kostelanetz 48.

(9) Cage was actually 15 years old in 1928, the year of the speech’s composition. He was a senior of the verge of graduating from high school.

(10) John Cage, “Preface to Lecture on the Weather,” Empty Words (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1979) 5.

(11) Sies 659.

(12) Thomas H. White, “The International Radio Week Tests,” United States Early Radio History, ed. Thomas H. White, 1 Jan. 2000, 16 Dec. 2001

(13) White.

(14) Willis K. Wing, “The 1926 International Radio Broadcasting Tests,” Radio Broadcast Feb. 1926: 463.

(15) Willis K. Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests,” Radio Broadcast Apr. 1926: 647.

(16) Arthur H. Lynch, “Plans for the Third of the International Radio Broadcast Tests,” Radio Broadcast Dec. 1925: 185.

(17) Wing, “The 1926 International Radio Broadcasting Tests” 462.

(18) J. R. Morecroft, “The March of Radio,” Radio Broadcast Apr. 1926: 654.

(19) Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 650.

(20) Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 650.

(21) Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 650–51.

(22) Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 647.

(23) White.

(24) Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 647.

(25) Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 647.

(26) Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 647.

(27) Cage said that his show began while he was in tenth grade and continued for two years. This would mean that his show began in the fall of 1925 or the spring of 1926.

(28) Duckworth 28.

(29) Overall, the Tests were a disappointment for radio enthusiasts, and capitalist radio stations were not solely to blame. Poor weather conditions had obtained, but perhaps the greatest obstacle was a technical one. The radiating receivers used by so many Americans (and banned in England) swamped the airwaves with “bloopers.” The Kansas Star reported: “The silent hour for the hundred of licensed broadcasting stations was only the signal for thousands of unlicensed bloopers to fill the air with such howling, squealing, and sputtering as make it a miracle indeed that any listeners were able to pick up foreign broadcasting?” Another letter complains, “It was like trying to pick out the buzz of one bee through the sound made by an entire hive, when I tried for Europe through the barrage of squeals.” Cited in Wing, “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests” 649.

Works Cited

Cage, John. “Other People Think.” John Cage. Ed. Richard Kostelanetz. New York: Praeger, 1970. 45-49.

---. “Preface to ‘Lecture on the Weather’.” Empty Words. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1979. 3–5.

Duckworth, William. “Anything I Say Will Be Misunderstood: An Interview with John Cage.” John Cage at 75. Ed. Richard Fleming and William Duckworth. Spec. issue of Bucknell Review 32.2 (1989): 15–33.

Hines, Thomas S. “Then Not Yet ‘Cage’: The Los Angeles Years: 1912-1938.” John Cage: Composed in America. Ed. Margorie Perloff and Charles Junkerman. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994.

Kostelanetz, Richard, ed. John Cage. New York: Praeger, 1970.

Lynch, Arthur H. “Plans for the Third of the Radio Broadcast Tests.” Radio Broadcast Dec. 1925: 185.

Morecroft, J. R. “The March of Radio.” Radio Broadcast Apr. 1926: 652–56.

Sies, Luther F. Encyclopedia of American Radio, 1920-1920. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000.

White, Thomas H.. “The International Radio Week Tests.” United States Early Radio History. Ed. Thomas H. White. 1 Jan. 2000. 16 Dec. 2001

Wing, Willis K. “The 1926 International Radio Broadcasting Tests.” Radio Broadcast Feb. 1926: 462–64.

---. “What Happened During the 1926 International Tests.” Radio Broadcast Apr. 1926: 647–651.