Birthday boy

31 Aug 2005

G.I. Joe is about to celebrate his 40th birthday. That is, G.I. Joe the twelve-inch action figure. In 1964 the Hasbro Corporation introduced Joe to the American public as the first posable soldier in toy manufacturing history. 1964 was also the year that US President Lyndon Johnson requested that Congress allow American troops to “freely intervene” in the Vietnam conflict. This request was the result of an attack on two US naval ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. It was also the year that Susan Sontag’s essay “Notes On Camp” was published in the Partisan Review.

In 1964 Hasbro was careful not to call G.I Joe a doll. In fact, during the first year that Joe was on toy shelves, a corporate memo circulated to Hasbro employees clearly stating that sales people who referred to Joe as a doll would not have their orders filled. Perhaps, if sales representatives had taken Sontag’s cue from her essay on Camp, and considered the power of quotation marks, they might have weathered the wrath of Hasbro’s corporate memos more gracefully. G.I. Joe was, indeed, not a doll. G.I. Joe was a “doll.”

This original “boy toy” became a staple in toy closets and was solely responsible for “outing” the fantasies of thousands and thousands of young boys in need of, well ... something.

Apparently Joe was not to be confused with other products on the market – products such as Barbie’s sidekick, Ken. Ken was introduced by the Mattel Corporation three years earlier, in 1961. And, although both “dolls” were virtually identical (amongst other things, Ken and Joe were both were eunuchs) there seemed to be a divide between each “doll’s” performance of masculinity. Joe seemed to gravitate toward “butch”, and Ken ... well, didn’t. However, these distinctions are irrelevant if we take heart in RuPaul’s insight that “you’re born naked and everything else you put on is drag.’’ Go, Ken. And, according to Ken “experts,” a white, human male has a 1 in 50 chance of actually achieving a Ken physique. I suppose the implication here is that a Joe body is not an impossibility. Go, Joe.

Apparently Joe was not to be confused with other products on the market – products such as Barbie’s sidekick, Ken. Ken was introduced by the Mattel Corporation three years earlier, in 1961. And, although both “dolls” were virtually identical (amongst other things, Ken and Joe were both were eunuchs) there seemed to be a divide between each “doll’s” performance of masculinity. Joe seemed to gravitate toward “butch”, and Ken ... well, didn’t. However, these distinctions are irrelevant if we take heart in RuPaul’s insight that “you’re born naked and everything else you put on is drag.’’ Go, Ken. And, according to Ken “experts,” a white, human male has a 1 in 50 chance of actually achieving a Ken physique. I suppose the implication here is that a Joe body is not an impossibility. Go, Joe.

During the first year that G.I. Joe made himself available to young boys, this intensely macho eunuch (and all his ultra-macho accessories) sold approximately $36.5 million dollars worth of product. $36.5 million dollars represents a whole lot of Joes. And, based on the number of Joes sold in that first year, it might be fun to do a “Twinkie statistic” and determine how many times all those Joes, daisy chained head to toe, would circumnavigate the globe. Go, Joe.

The original G.I. Joe line up included a soldier, a sailor, a marine, a pilot and, for a very brief time a nurse. I know, this line up demands the question, “what about an Indian, or, perhaps a biker in chaps?” Presently a G.I. Joe Nurse in good condition is worth a very collectable $6,000. Unfortunately, in July, 2003, G.I. Joe Nurse was outranked by the original G.I. Joe prototype which was auctioned for $600,000.

This original “boy toy” became a staple in toy closets and was solely responsible for “outing” the fantasies of thousands and thousands of young boys in need of, well ... something. In the early days Joe’s hard, plastic body measured a proud 12 inches. And, although he was marketed as an “all American hero,” Joe was manufactured in Hong Kong, Japan, and, at times, sweat shops in Taiwan. In 1976, on the eve of the United State’s bicentennial celebration, Hasbro halted the production of G.I. Joe. Apparently the petroleum based plastic that he was extruded from was too expensive to produce during the OPEC oil embargo.

This original “boy toy” became a staple in toy closets and was solely responsible for “outing” the fantasies of thousands and thousands of young boys in need of, well ... something. In the early days Joe’s hard, plastic body measured a proud 12 inches. And, although he was marketed as an “all American hero,” Joe was manufactured in Hong Kong, Japan, and, at times, sweat shops in Taiwan. In 1976, on the eve of the United State’s bicentennial celebration, Hasbro halted the production of G.I. Joe. Apparently the petroleum based plastic that he was extruded from was too expensive to produce during the OPEC oil embargo.

Sadly, when Joe was reintroduced in 1982 he had been emasculated to a flaccid 3 3/4” length. Perhaps there was something meaningful about this new, more modestly sized, Joe. That is, something more meaningful than a “dick joke.” Perhaps his smaller size reflected something about the condition of his own ego, or the condition of the American psyche in a post-Vietnam era, or both.

G.I. Joe (the action figure) was modeled after the 1945 William Wellman movie, The Story of G.I. Joe, starring Robert Mitchem and Burgess Meredith. In 1931 Wellman also directed James Cagney and Jean Harlow in the brutally machismo film Public Enemy. G.I. Joe (Wellman’s movie character) was based on the life of Ernie Pyle, a World War II war correspondent who found his voice through a typewriter.

In Ernie Pyle’s 1943 book, Here Is Your War, he wrote, “I don’t know whether it was their good fortune or misfortune to get out of it (Tunisia) so early in the game. I guess it doesn’t make any difference, once a man has gone. Medals and speeches and victories are nothing to them any more. They died and others lived and nobody knows why it is so.” G.I. Joe (the action figure for young boys) did not find his voice through a typewriter, he found his voice through the violence of a rocket launcher.

In 1964, when toy stores were all about G.I. Joe (the action figure), the TV program Gomer Pyle made its broadcast premiere. Gomer Pyle was based on a character that Jim Nabors played in the Andy Griffith Show, one season earlier. In the Andy Griffith Show, Gomer was a gas station attendant who was drafted into the armed forces. Nabors developed his character for The Gomer Pyle show making the program the first “spin off” television series in that medium’s brief history. One hundred and fifty episodes of the series aired from 1964 to 1969.

In 2002, Gomer Pyle (the TV character) was honored by the United States Marine Corps for representing the military in “good faith.” Jim Nabors accepted the award on Gomer Pyle’s behalf. In the TV program Gomer Pyle often found himself getting into trouble as a result of his ability to resolve problems with his intellect, not his fists. It seems that he might have been more at home with a typewriter than a rocket launcher.

Ernie Pyle (the war correspondent) wrote for the U.S. Military publication, Stars & Stripes. He died on April 18, 1945. Ernie Pyle was one of 15,000 American troops lost in battles in and around Okinawa. During that same military campaign 150,000 Japanese troops were killed including 85 nurses who were mistaken for Japanese infantry by U.S. forces. The nurses were burned to death in a cave where they were hiding. In that case, US troops found their collective voice through “flame throwers,” hand grenades, and stupidity.

In 2001 James Tobin wrote a biography about war correspondent Ernie Pyle. In the book, the author criticized Pyle for glorifying the brutality of World War II in naïve and simplistic ways. In an essay titled “The Death of Captain Waskow” (published by the Washington Daily News on January 10, 1944), Pyle wrote this about his experiences in World War ll: “I don’t know who that first one was. You feel small in the presence of dead men, and ashamed at being alive, and you don’t ask silly questions.”

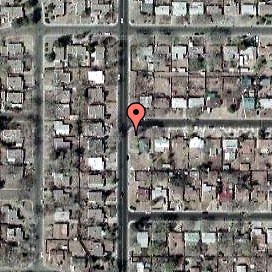

Before he enlisted in the United States Army, Ernie Pyle, and his wife Jerry, built a small five-room cottage that is still located at 900 Girard Boulevard S.E, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Today his home has been converted into a branch of the public library system. The Ernie Pyle Memorial Library was established in 1947, two years after the writer’s death. Pyle’s old bedroom now houses the library’s small but distinguished collection of fiction. The bathroom, where Jerry, in a drunken fit, attempted suicide with a pair of scissors, is the library’s periodical archive. In the living room, surrounded by shelves of “best sellers,” Pyle’s typewriter, war medals, and select hand-written letters to his wife are displayed in a glass case.

Prior to Pyle’s brief tenure in Albuquerque, the couple spent seven years crisscrossing the United States in a travel trailer. From his trailer, Pyle sent his employer, the Scripps Howard newspapers, a series of articles about his experiences on the road. At the end of that nomadic period Pyle, Jerry, and Pyle’s writing career were worn out and exhausted. It is a popular notion that World War II saved Pyle’s writing career.

I live four blocks from the Ernie Pyle Memorial Library and often walk there to borrow books and exercise my dog. It’s a nice walk. That is, it’s a nice walk if you ignore the many sonic booms and occasional explosions generated from the nearby Kirtland Air Force base. Kirtland Air Force Base occupies 52,000 acres south of Albuquerque. It’s really, really big. One can walk to the front gate of the base from the Pyle library.

I live four blocks from the Ernie Pyle Memorial Library and often walk there to borrow books and exercise my dog. It’s a nice walk. That is, it’s a nice walk if you ignore the many sonic booms and occasional explosions generated from the nearby Kirtland Air Force base. Kirtland Air Force Base occupies 52,000 acres south of Albuquerque. It’s really, really big. One can walk to the front gate of the base from the Pyle library.

The annual budget to operate Kirtland is approximately four billion dollars. That is double the amount of money spent on the New Mexico Department of Education to help kids develop their intellect, not their fists. The 35,000 employees in the New Mexico Department of Education serve 350,000 students, in 89 school districts throughout the state.

On August 6, 1945, less than four months after Ernie Pyle’s death, the Enola Gay dropped two New-Mexico-made atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima that resulted in deaths equaling the total number of students presently served by the New Mexico Department of Education.

Buried in caves that are cut deep into the hills surrounding Kirtland Air Force Base (which I can see from my backyard), the U.S. military stores the world’s largest stockpile of nuclear warheads.

At the front gate of Kirtland Air Force base in Albuquerque, armed guards are stationed behind small mountains of sandbags. And there, in front of the sandbags is a small wooden sign that reads “Today’s World threat: High.” The sign reminds me of those you might see in a national forest where an image of Smokey Bear alerts you to the potential danger of campfires. However, at the front gate of Kirtland Air Force Base there are no campfires, no roasting marshmallows, and no Smokey Bear. At the front gate of the Kirtland Air Force Base there are only young, frightened soldiers armed with loaded, automatic weapons, and orders to kill.

For a brief time during World War II, Smokey Bear was used to spread false and hateful messages about the Japanese. A 1944 Smokey Bear ad campaign suggested that forest fires were the direct result of Japanese (“monkey-men”), kamikaze sorties. The ad read “Our Carelessness, Their Secret Weapon.” Shame on Smokey.

In Capitan, New Mexico there is a museum dedicated to Smokey Bear. There, one can view these wartime ad campaigns, visit Smokey’s grave and buy Smokey Bear “T” shirts.

Smokey died in 1976, at the age of 28, while imprisoned in the Washington D.C. Zoo. His remains are buried at the Smokey Bear Museum in Capitan, New Mexico. At the museum, a tour guide reminds visitors that Smokey’s full name is, in fact, Smokey Bear, not Smokey “the” Bear. Apparently, including “the” would be equivalent to saying Santa “the” Claus.

Back to 1964 (the year of G.I. Joe) and all its brutality. U.S. president Lyndon Johnson spent those twelve months preparing American troops to fire bomb North Vietnam in 1965. In Florida, Cassius Clay beat the living crap out of his rival, Sonny Liston, at the Convention Hall in Miami Beach. That same year, Dr. Martin Luther King also made an appearance in Florida. Unfortunately he was arrested in St. Augustine for leading a march in opposition to certain racial segregation laws in that state.

Internationally, things didn’t look much better. Brazil was overtaken by military dictator, Castelo Branca. And his dictatorship remained in place for the next 25 years. During his reign, Branca took the opportunity to assemble South America’s first CIA-trained (School of the Americas in Georgia) death squads. In Rhodesia, a post-colonial coup put Kamazu Banda in power (Britian had colonized Rhodesia prior to 1964). Banda terrorized his population for the next 30 years in what many Africans consider to be the most repressive government in the history of that continent. Banda secured his power by killing every last one of his political opponents and then instituting a single party political system. Duh. In the United States, I wonder if the popularity of G.I. Joe (the action figure) might have been a sanitized reflection of all this brutality?

On July 5, 1964, in Norwalk, Connecticut, I celebrated my sixth birthday. And, to celebrate, my parents hosted a “G.I. Joe Birthday Party.” Hasbro made the party really easy. Not only did they sell the twelve-inch man-dolls (action figures), but there were a whole range of official G.I Joe after-market products including plastic grenades, military vests, and automatic weapons, all of which were young-boy-size. So, for my party, everyone came dressed as his or her particular version of G.I. Joe. We ate cake from official G.I. Joe mess kits, and when our bellies were full we engaged in “G.I. Joe War Games.” Playing “War” was a lot like playing “Tag – You’re It” only we were armed to the teeth and ready to defend freedom, justice, and perhaps another slice of birthday cake.

Two famous artists grew up in the town where I celebrated my birthday on July 5, 1964. They were both twelve years old when I turned six and are now living in New York City. Joe Coleman is a performance artist who blows himself up with fireworks and bites the heads off of live rodents. He receives grants from the New York State Council on the Arts to perform these high-art rituals. He might have been fun to have on our side during our war games.

Cary S. Leibowitz is a painter who goes by the pseudonym “Candyass.” He grandstands his sense of self-reproach by painting slogans such as “kick me,” and “don’t hate me because I’m mediocre.” Leibowitz’s paintings sell for a lot of money. Aside from these two characters, Norwalk is just a little, sleepy coastal town. It seems to have been overwhelmed by the obscene amount of wealth in nearby Greenwich, Connecticut (one of the most affluent communities in the United States and, possibly the universe).

Greenwich is the town where George Bush Senior grew up during the 1940’s. There, he began raising his family before packing up camp and moving to Texas. While living in Greenwich, the Bush family employed three maids and an individual chauffeur for each of their five children. Apparently, all the chauffeurs were needed to shuttle the children back and forth to the Greenwich Country Day School. The Greenwich Country Day school is a private school whose reputation for their arts curriculum was well known at the time.

After George Bush left Connecticut to become president of the United States (1988), he proceeded to make some of the usual administrative adjustments that presidents do when they are elected. One of those adjustments included firing John Frohnmeyer who, at the time, was the chair of the National Endowment for the Arts. Frohnmeyer’s successful management of this important cultural organization was well known and respected. However, the newly elected president immediately began reducing the size and scope of the NEA. Between 1992 and 1996 the NEA lost 55% of its annual budget.

Today things have gotten even worse. Presently it is close to impossible for artists such as Joe Coleman and Cary S. Leibowitz to receive federal support for their creative activities. In fact, 2001 statistics indicate that the United States federal government spends only $5 per capita to support cultural events compared to the $50 per capita spent by Canada, France, and Sweden. And, one might note that Germany and Finland top this list in that their support for the arts is close to $90 per capita.

Back to my birthday. For my sixth birthday, my uncle Sam (his name really is Uncle Sam) who lives in Florida, sent me a check for $20 to buy anything I wanted. At the time $20 was a big deal to both me and my parents. So, as a result, my parents insisted on facilitating the whole operation. We drove to Kiddytown toy store located in the heart of Norwalk, Connecticut. At the time Kiddytown represented the absolute epicenter of my entire universe. They had an expansive inventory of G.I. Joe products. Kiddytown was located right across the street from Hank’s Novelty Shop. Hank’s had an expansive inventory of cigars, porno magazines and fireworks.

At that time it was illegal to sell fireworks in Connecticut. If, however, your dad knew Hank, that is, if he were a regular customer (which meant he purchased a reasonable amount of cigars and pornography), you might get lucky. I’d like to imagine that Joe Coleman was one of those regular customers who got his start as an exploding performance artist through the firecrackers he might have purchased at Hank’s Novelty Shop.

Back to my birthday. Unfortunately, on that day, Uncle Sam’s birthday money was not to be spent at Hank’s Novelty Shop. We were going to Kiddytown. After studying the isles, my Dad suggested that I might be interested in a green, plastic, military troop carrier. My G.I. Joe could ride around in it. However, I had my eyes focused on something else.

And, I’d like to think that what I had my eyes focused on was simply a knee-jerk response to all the G.I. Joe-ness that surrounded me and my playmates that year. I wanted to purchase a tea set and have a tea party.

The decision was complicated by a variety of things including my dad’s vision of who he wanted his son to be. He had a specific sense of his boy that definitely did not include tea sets. My dad had been a boxer in college (he literally found his voice through his fists) and now taught Wood Shop classes at a Junior High school in Norwalk. It was a “manly” kind of thing to teach. He used to take pleasure in humiliating the boys with long hair by making them wear hairnets “just to be safe in the shop.” Years later, and for a very, very brief time, I was employed as a substitute teacher in the same Junior High school. I had long hair and wore clogs. After being humiliated by student football players (it was definitely the clogs), I never went back.

Back to the tea set. Yes, my parents reluctantly bought the tea set. However, before I had the chance to unwrap the package, or even open the box, the whole thing disappeared – right into “thin air.” Months later, while I was rummaging around in our attic for a Halloween costume (well, OK, it wasn’t exactly Halloween – I was just playing “dress up”), I actually found the tea set. It was hidden under a pile of my mom’s dresses and skirts, in a place where, perhaps, a young boy might never look. I didn’t tell anyone about my discovery.

And for the next few years, when no one was home, I would sneak into the attic, uncover the tea set, and there, surrounded by all my invisible friends (no G.I. Joe) we’d sip tea and have fantastic parties. From the attic window we looked out on the neighborhood kids and took quiet pleasure in knowing that we didn’t have to participate in all those hateful games they played in the street below (Dodge ball, Monkey In The Middle, Tag-You Are It, Blind Man’s Bluff, etc). When the parties ended, we were always careful to place everything back exactly as we had found it. No one ever knew. No one ever suspected.

I don’t know what ever happened to my invisible friends or for that matter, the tea set. Both have been lost to the past. However, I do know that two years later, when I was eight years old, I asked Santa Claus if he might bring me an Easy Bake Oven for Christmas.

Bryan KonefskyAlbuquerque, New Mexico

◊