Lost cities

8 Sep 2005

Hope in the presence of small teams enacting huge efforts to thwart monumental destruction

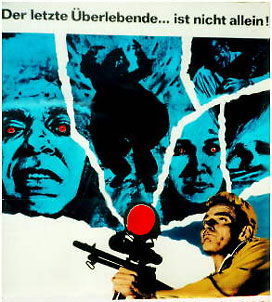

In an essay by Frank Krutnik appearing in the anthology The Cinematic City edited by David B. Clarke, discussion of the Hollywood noir thriller “as a means of articulating a crisis of spatial and psychological indeterminacy and sense of disorder in urban America of the 1940s and 1950s” (Parsons, 1999) examines Hollywood film of that period from the standpoint of the city as personification of anxieties and dilemmas at the heart of social culture. Extrapolating on this way of looking at the city in film for a discussion of more recent films, the American city can be seen as declining on a variety of grounds or as personifying human-like attributes of one sort or another. One great example is Boris Segal’s The Omega Man (1971) where Los Angeles is shown to be, in a long aerial sequence of images, a virtual no man’s land; void and desolate, a city without human soul, all the more weirdly relevant when the lone hero of the film, played by right-wing actor, Charlton Heston, is found driving his big car through the pathetic, empty maze which once was a living place.

In an essay by Frank Krutnik appearing in the anthology The Cinematic City edited by David B. Clarke, discussion of the Hollywood noir thriller “as a means of articulating a crisis of spatial and psychological indeterminacy and sense of disorder in urban America of the 1940s and 1950s” (Parsons, 1999) examines Hollywood film of that period from the standpoint of the city as personification of anxieties and dilemmas at the heart of social culture. Extrapolating on this way of looking at the city in film for a discussion of more recent films, the American city can be seen as declining on a variety of grounds or as personifying human-like attributes of one sort or another. One great example is Boris Segal’s The Omega Man (1971) where Los Angeles is shown to be, in a long aerial sequence of images, a virtual no man’s land; void and desolate, a city without human soul, all the more weirdly relevant when the lone hero of the film, played by right-wing actor, Charlton Heston, is found driving his big car through the pathetic, empty maze which once was a living place.

So starts the 2004 version of their seminal presentation, “Lost Cities” given by research and design collaborative Archimedia in Brisbane, Australia in which sequences from The Omega Man emerge as part of a critique underpinning a deeper analysis of the presence of the ‘lost city’ in film, art, and architecture. Such images, of anxiety, fear, and hope, abound in western film, photography and the arts. It is more recently, in the strange post 9/11 Bush-war reality, that American cities have joined ranks among those of Europe and the Middle East to become the actual terror centres they were faked to become through special effects in previous cinema history. Indeed, the city of New York has long personified a state of social discombobulation with its sheer density of signs and towering buildings. New York type cities have played victim, lover, Other, and psychic enemy Number One in dozens of popular films where its characterization is embodied in the architecture, showered in cinematic light (Fritz Lang’s Metropolis) or literally imagined as a maximum security prison in films such as Escape from New York, as a veritable “hellhole” in The Towering Inferno and as a breeding ground for lizard-cum-evil destroyer in remakes of Godzilla. Spielberg’s A.I. presupposed Manhattan’s skyline almost entirely drowned; a lost civilization of lost memory retrievable only through alien life forms and genetically engineered identity. In the upcoming version of King Kong we are bound to gain yet more perspective on a besieged New York now without the Twin Towers. What monumentality will our cities embody next?

So starts the 2004 version of their seminal presentation, “Lost Cities” given by research and design collaborative Archimedia in Brisbane, Australia in which sequences from The Omega Man emerge as part of a critique underpinning a deeper analysis of the presence of the ‘lost city’ in film, art, and architecture. Such images, of anxiety, fear, and hope, abound in western film, photography and the arts. It is more recently, in the strange post 9/11 Bush-war reality, that American cities have joined ranks among those of Europe and the Middle East to become the actual terror centres they were faked to become through special effects in previous cinema history. Indeed, the city of New York has long personified a state of social discombobulation with its sheer density of signs and towering buildings. New York type cities have played victim, lover, Other, and psychic enemy Number One in dozens of popular films where its characterization is embodied in the architecture, showered in cinematic light (Fritz Lang’s Metropolis) or literally imagined as a maximum security prison in films such as Escape from New York, as a veritable “hellhole” in The Towering Inferno and as a breeding ground for lizard-cum-evil destroyer in remakes of Godzilla. Spielberg’s A.I. presupposed Manhattan’s skyline almost entirely drowned; a lost civilization of lost memory retrievable only through alien life forms and genetically engineered identity. In the upcoming version of King Kong we are bound to gain yet more perspective on a besieged New York now without the Twin Towers. What monumentality will our cities embody next?

[These films] hold out some hope for the thin-edge of human progress; some warmth, love, and humanity still burns within each narrative story in the form of small, rugged teams of good characters – survivors engaged in huge acts of self-defense against the predominance of lurid evil

Less monster movies and more about technology, corruption, identity theft, and the loss of societal centre, two popular films depict Washington DC as a madhouse of crime and denial. Enemy of the State opens in a nature preserve where top secret murder among national leaders is taking place, only to bounce from high tech NSO offices to the hero’s ransacked Georgetown home and then into the streets. Will Smith morphs from a successful labor lawyer to an “unidentified” man pitted in a battle for his life against the mobile all-seeing forces of a technologicalized government. No one is safe and accountability is rare in this free-for-all panopticon. Early sequences set up the city as one fractured by the spectacle; spied upon and listened in on at every turn by Big Media and on professional laptops from the back of an NSO supplied van. It is a decentred city without walls or protection; or social contract. At the end Brill (played by the marvellous Gene Hackman in a throwback to his role in The Conversation) sabotages the villain’s home phone, bank account, and credit history with the mere use of a wireless laptop and mobile phone. It is an heroic, hackerist gesture and testimony to the power of the personal.

Less monster movies and more about technology, corruption, identity theft, and the loss of societal centre, two popular films depict Washington DC as a madhouse of crime and denial. Enemy of the State opens in a nature preserve where top secret murder among national leaders is taking place, only to bounce from high tech NSO offices to the hero’s ransacked Georgetown home and then into the streets. Will Smith morphs from a successful labor lawyer to an “unidentified” man pitted in a battle for his life against the mobile all-seeing forces of a technologicalized government. No one is safe and accountability is rare in this free-for-all panopticon. Early sequences set up the city as one fractured by the spectacle; spied upon and listened in on at every turn by Big Media and on professional laptops from the back of an NSO supplied van. It is a decentred city without walls or protection; or social contract. At the end Brill (played by the marvellous Gene Hackman in a throwback to his role in The Conversation) sabotages the villain’s home phone, bank account, and credit history with the mere use of a wireless laptop and mobile phone. It is an heroic, hackerist gesture and testimony to the power of the personal.

In the lesser known but highly important Arlington Road (1999) starring Tim Robins, Jeff Bridges, and Joan Cusack, director Mark Pellington portrays American suburbia as a paranoid cul-de-sac for self-righteous home grown right-wing terrorism; a hide out for would be Oklahoma City bombers who recruit children into their miasma of negativity; the American version of a Nazi youth program for those with axes to grind against authority and their own screwed up fathers and mothers. The film takes place in a nebulous community outside Washington DC; a community of nice and normal family homes, where a little boy’s hand is casually blown off while playing with loose explosives and is saved by Jeff Bridges who plays the only throwback to a time of political accountability. His character, as a college history professor with a personal vendetta (his wife was an FBI agent killed in an ambush by some hillbillies) whose income bracket affords him an upscale lifestyle and a new friendship in the boy’s parents (Robins and Cusack), embodies the tragic hypocrisy of the American system when Bridge’s liberal beliefs in law and order begin to do him in. The remainder of the film is a chilling portrayal of fascism; a normalizing sameness and obsession with suspicion and safety.

In the lesser known but highly important Arlington Road (1999) starring Tim Robins, Jeff Bridges, and Joan Cusack, director Mark Pellington portrays American suburbia as a paranoid cul-de-sac for self-righteous home grown right-wing terrorism; a hide out for would be Oklahoma City bombers who recruit children into their miasma of negativity; the American version of a Nazi youth program for those with axes to grind against authority and their own screwed up fathers and mothers. The film takes place in a nebulous community outside Washington DC; a community of nice and normal family homes, where a little boy’s hand is casually blown off while playing with loose explosives and is saved by Jeff Bridges who plays the only throwback to a time of political accountability. His character, as a college history professor with a personal vendetta (his wife was an FBI agent killed in an ambush by some hillbillies) whose income bracket affords him an upscale lifestyle and a new friendship in the boy’s parents (Robins and Cusack), embodies the tragic hypocrisy of the American system when Bridge’s liberal beliefs in law and order begin to do him in. The remainder of the film is a chilling portrayal of fascism; a normalizing sameness and obsession with suspicion and safety.

Arlington Road depicts the city of Washington as an anemic backdrop to militant unseen forces of absolutism and separatism to corrupt humanity; it is a place which has succumbed to right-wing extremism. Ultimately, it is a film which points out how in an era of such agendas – civil rights no longer mean anything. It is a film in which the American national capital has lost the power of its architecture to communicate and in this sense points out the distorted reality of conservative nationalism as a dystopic vision of privatization in which lawless violence and extreme totalitarianism might well take over. Yet, as my title would suggest, both films, like The Matrix trilogy does, hold out some hope for the thin-edge of human progress; some warmth, love, and humanity still burns within each narrative story in the form of small, rugged teams of good characters – survivors engaged in huge acts of self-defense against the predominance of lurid evil – and in this sense they are culture which reframes the ethical and political spectrum of our time.

Molly Hankwitzmollybh@netspace.net.au

◊

Clarke, David B. The Cinematic City. London: Routledge, (1997).

Parsons, Deborah L. ‘Urban montage’. Film-Philosophy : Volume 3 Number 39, September 1999. Book review.

www.film-philosophy.com/vol3-1999/n39parsons

King Kong

www.killermovies.com/k/kingkong/

Enemy of the State

www.imdb.com/title/tt0120660/

The Towering Inferno

www.imdb.com/title/tt0072308/

Godzilla

www.imdb.com/title/tt0120685/

The Omega Man

www.imdb.com/title/tt0067525/

The Conversation

www.imdb.com/title/tt0071360/

Arlington Road

www.imdb.com/title/tt0137363/

A.I.

www.imdb.com/title/tt0212720/

San Francisco Public Library September calendar, 2005, Friends of the Library.

Archimedia

archimedia.sytes.net/