Das Netz review

25 Oct 2005

www.t-h-e-n-e-t.com/

www.expolar.de/kybernetik/

Lutz Dammbeck’s film Das Netz (The Net) provocatively and methodically connects the dots which link the CIA, their covert mind-control LSD research, the anti-war LSD fuelled counterculture, the personal computer, and the Internet with Ted Kaszynski, the man many know as the “UNABOMBER.”

Lutz Dammbeck’s film Das Netz (The Net) provocatively and methodically connects the dots which link the CIA, their covert mind-control LSD research, the anti-war LSD fuelled counterculture, the personal computer, and the Internet with Ted Kaszynski, the man many know as the “UNABOMBER.”

The filmmaker’s own fascination with this character is itself a curious thing – we see the filmmaker, detective-style, tracking down his leads until some kind of broad stroke picture can emerge of who this man is and what might have motivated his bomb campaign during the 1990s. The use of first person narrative – a hand drawing with a pen on paper a bunch of named circles and lines connecting them of who was who and who was connected to what – is interspersed with interviews with key people. This is a gripping and disturbing story and something of the Euro-sceptic flipside to the official California school of WIRED magazine’s breathless technological deterministic view of “tech” always being good, always making things better, and always representing the best that the USA has to offer.

Europeans, particularly the very highly educated ones, have long viewed the USA and its fascination with its own technology, mythology, and machinery with nothing if not an ambivalent scepticism, for no other reason that even Western Europe saw itself on the receiving end (like it or not) every day since 1945 of white goods, cars, machines, TV, radio, music, and culture in general.

Das Netz revisits very, very familiar ground for those historians and media archaeologists like myself who have a vested interest in keeping the story “clean,” in which the good guys (artists, philosophers like Leary, Brand, Weiner, Fuller) are on one side and the bad guys (the evil CIA, the US Military, project MK Ultra et al) are on the other.

This must have been particularly keenly felt in the Eastern Bloc countries, where not only was the evidence for the USA’s own relentless push to influence the West in most stark evidence by its absence in the East, but the view reinforced daily via Pravda and other official channels that the USA was corrupting Europe with its relentless technological advances in any way it could. Growing up in England I remember vividly the ambivalence which surrounded the very fact of US domination. We loved it and we hated it. We loved it because we hated it. And we hated it because we loved it. Like a stern mom, the USA was always there, always “on” and always would be.

And here within the USA’s own borders is the auto-sceptic, a man with a Polish name, Kaszynski, the loner, the isolated woodsman holed up in his distant rural cabin dispatching random and deadly pipe bombs in the form of booby-trapped parcels to unsuspecting scientists. Why did he do it? Because he was sick of seeing the world go to hell in a hand-basket at the hands of self-styled captains of techno-industry, science and technology, advocating their responsibility as scientists to prevent the world from losing its direction. Or something like that. Read the manifesto.

And here within the USA’s own borders is the auto-sceptic, a man with a Polish name, Kaszynski, the loner, the isolated woodsman holed up in his distant rural cabin dispatching random and deadly pipe bombs in the form of booby-trapped parcels to unsuspecting scientists. Why did he do it? Because he was sick of seeing the world go to hell in a hand-basket at the hands of self-styled captains of techno-industry, science and technology, advocating their responsibility as scientists to prevent the world from losing its direction. Or something like that. Read the manifesto.

Kaszynski as an idea, more than the man himself appear to be a source of deep fascination for Dammbeck, almost an obsession. Men will travel all their lives to film themselves looking for other men with whom they see something to closely identify with. The obsessed goes in search of the obsessed. This double fascination (which becomes fascinating to outsiders like the viewers, which is to say, us) is met in equal measure by understandable revulsion and bitter resentment by his victims and those who know them when Dammbeck finally meets them and interviews them on miniDV. The laptop and the miniDV have allowed this type of essay-verite to happen at all and this fact alone is worth a mention.

It is almost embarrassing to see Dammbeck interview those who clearly are totally and utterly mystified and angered as to why anyone would reserve anything but total contempt for Kaszynski and his ‘tactics’. How can Dammbeck maintain anything like a level head as his interviewees squirm uncomfortably when asked about the subject?

Whatever Dammbeck’s motivation (to get just this sort of ‘edgy’ footage presumably), to ram this subject home to those most affected smacks of a kind of intellectual hubris, (if not outright sadism) akin to sensationalist TV reality shows masking the antics of urban police making arrests for the cameras. If he were an academic, as I am, I’d call into question his ethics. I don’t like watching it, and maybe that’s the point, I’m not supposed to. It is like the watch-me-no-turn-me-off double take of lurid explicit porn. It is like watching a filmed accident or assassination. It is like having your nose rubbed in your own worst home truths, and I think this latter point is really at the heart of Dammbeck’s modus operandi. He wants us to watch him doing this to those people. How answerable are these people anyway? All that links some of them to Kaszynski is the fact that they were mentioned in the New York Times about their work, and had their hands blown off by his bombs. These ones are at least still around to talk to cameras. Others were not so fortunate.

Dammbeck’s status as East German film-maker might partly explain this brand of interrogation as reportage. East Germany, like much of the Soviet Bloc for decades elevated its top scientists and thinkers via state backed programs and university postings, never thinking to separate an individual’s genius from the long-term goals and aims of the State. All states do this of course, but the Soviet bloc made totally official any gifted student’s role in the eventual planning and running of the Communist (state capitalist) regime.

Kaszynski, the ultimate once-upon-a-time showcase poster-boy mathematical intellectual turned woodsman and survivalist isolationist-killer was himself the bitter fruit of the US’s university elite trained cold war and space race military/intelligence system. Like many of his counterparts in the Eastern Bloc, his fate and his status as LSD guinea pig was kept top secret. His decline into a Conradian heart of darkness, that sovereign place so few emerge from once well on their way was also an official secret.

So many radical and cutting edge European technological developments found a fertile home with ample finances in the USA after world war two, and these included liquid fuel rocketry (Germany) which led to the US dominance of space, LSD (Switzerland) from migraine treatment to paradigm buster. Even the idea at least of the personal computer had some of its origins in Europe. The USA took them from Europe and developed them in the service of its own interests.

Dammbeck uncovers the ways in which the government and business tried to unravel the mysteries of what makes human beings become fascistic and how this project was linked ultimately to ideas surrounding cybernetics, distributed systems such as Buckminster Fuller’s engineering, and the work of those who developed ARPANET, now the Internet. Nice work if you can get it and you can still get it if you try. Look no further than Stanford, Harvard, and the many spin-off firms of Silicon Valley and the entire mind-set of Northern California. This place is not just a geographical place, it is an entire mindset which keeps defining the way the future ends up looking and feeling for better or worse, and much of it has to do with countless fortunes in the form of cold-war and space-race dollars pouring through the pockets of tripped out hippies, freaks, and weirdos. Today the military and the entertainment sectors are running the show. The military today, as Bruce Sterling puts it, was once run like General Motors, but is now run like Microsoft. Competitors are tokens, a joke, and it now can shape both planet earth and outer space itself in its image.

It is a genuine tragedy that Dammbeck has not ever experienced the acid tests of the 1960s. I often lament that I never could take Keysey’s bus into the other dimension and then build a world out of experiments in media to try to rectify what the military had done.

Every time I see the film (and I have seen it over and over again, fascinated by the very fact of its existence) I ask myself: how can a man make a film about a 1960s counterculture that he clearly has no direct experience of? Should someone like myself, so enamoured of that story and with so much invested in that story having a happy outcome let its telling be so easily equated with its ugly flipside? Cannot the separation – that art and experimentation are fundamentally at odds with the ways they get co-opted by the forces of evil be preserved? Should not all of us that have a stake in this story make sure that this is the official version? I am outraged that Dammbeck has made me have to rethink the whole narrative.

How can Dammbeck draw us into his pursuit of one man by reminding us of a time that was self-evidently needed and important (the 1960s counterculture) and then set himself up as so confidently a judge that set of relations by implying that he is willing to factor in at least some of the ideas of the Unabomber? Only Stewart Brand dares to concede that maybe technology can, as the Unabomber says in his Manifesto, “go too far.”

The nature / culture divide like that of the city vs. country has underpinned a long standing cultural “problem” in Germany since it became a state in the 1800s. Mensch / Natur / Technik is the triumvirate which haunts western Europe and yet holds out as its best hope.

The horrors of technology fused with skewed picturesque national folklore were more than evident during the period of the rise of Nazism. The Stuka and the cuckoo clock were fused in the minds of most pro-Nazi Germans as one and the same type of imagined techno-kitsch utopia. Technology was viewed by fascists as totally neutral when the pseudo-science behind its obscene genocidal uses were fully and wilfully applied.

This familiarity with the dark ease with which technology can become so easily fused with picturesque folklore is nothing if not characteristic of the ways in which “geeks,” “hippies,” and “cyberpunks” bandy about computers alongside fantasies of worlds populated by hobbits, goblins, and flying hackers like NEO in The Matrix. Is crypto-fascism at the heart of any kind of technological fetishism? I’d have to say no, in my experience, but there can often be detected the whiff of danger from places which seemed innocent enough in retrospect. Like the Apollo missions which so easily now have become the race to fill space with weapons and “rods from gods.” Like the proliferation of nuclear weapons which can now be carried in briefcases and which threaten whole cities and the trade of which brings organised crime and fanatical religious cults into the same trade arena.

Dammbeck reminds me of that East European (Polish?) one learns about on the “making of doco” on the DVD, who saw Easy Rider over and over again, making it nothing less than a personal philosophy, a crutch to hold oneself up on as one endured the misery of a life under bleak drab authoritarianism. Until the day they finally meet Dennis Hopper and declare this fact breathlessly to their hero, only having lived the best possibilities of the Californian techno-utopia through the filter of a story once-removed. In Europe we have all had to live the American dream by proxy, even those of us who get to one day actually get to live here, the answer to a dream, we can never have lived the Californian sea of possibilities like the locals have, and do everyday.

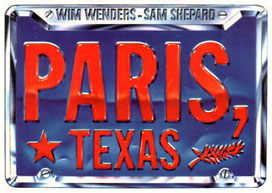

Like Wim Wenders and his depressing if accurate and empowering view in Paris Texas of the USA as a wasteland of lost aimless wanderers, only just barely keeping it together. Kaszynski is a bit like Wender’s own Ulysses character in that film played by Harry Dean Stanton. Stanton’s Travis wanders in the desert, lost, alienated from all, but somehow finally at ease with his outsider status, replete with ‘white-trash’ icon, the red baseball cap. One learns in the film during the ill-fated reunion between Travis and his ex-wife that in a moment of madness, he had chained her to their trailer home's bed before setting it alight and walking away, to prevent her ever leaving him.

Like Wim Wenders and his depressing if accurate and empowering view in Paris Texas of the USA as a wasteland of lost aimless wanderers, only just barely keeping it together. Kaszynski is a bit like Wender’s own Ulysses character in that film played by Harry Dean Stanton. Stanton’s Travis wanders in the desert, lost, alienated from all, but somehow finally at ease with his outsider status, replete with ‘white-trash’ icon, the red baseball cap. One learns in the film during the ill-fated reunion between Travis and his ex-wife that in a moment of madness, he had chained her to their trailer home's bed before setting it alight and walking away, to prevent her ever leaving him.

Like John Wayne’s unhinged Ethan Edwards of the Searchers Kaszynski as Dammbeck paints him is the misunderstood ranter of truths told too strongly for the world to bear. He is that most popular of figures in Europe – the dark flipside to the American dream – the uprooted and self-exiled angel of death, who (like the dead Comanche Edwards shoots in both eyes to deny his passage to heaven) is condemned forever to ‘wander between the winds’.

I am fascinated by Das Netz for reasons I cannot explain. I love how Dammbeck carefully articulates the delicate cross-pollination of ideas which in the 60s and 70s and 80s spun off into counterculture forms like the amazing “acid tests” of Ken Kesey, the Whole Earth Catalog of Stewart Brand, the minimalist art and media movements of the late 1960s and 1970s and the fine art and experimental film and multimedia projects of Fluxus and others in New York and San Francisco later became reified into the big business model which dominates life as we know it today. I love this story partly because I see myself as having had a small role in it, being old enough to remember the time before the personal computer (my office at work is filled with mothballed Macs and PCs – I cannot bear to see them wasted) and the Internet, both played a crucial role in my development as an artist and as a filmmaker. But so did the myths of the 50s, 60s, and 70s anti-war- and anti-authority-driven countercultures. Where these two poles fuse and overlap and the points on the mind-map are many is where anyone who uses a computer and a camera should find a place for themselves, or risk living (in my view) outside of history.

I am fascinated by Das Netz for reasons I cannot explain. I love how Dammbeck carefully articulates the delicate cross-pollination of ideas which in the 60s and 70s and 80s spun off into counterculture forms like the amazing “acid tests” of Ken Kesey, the Whole Earth Catalog of Stewart Brand, the minimalist art and media movements of the late 1960s and 1970s and the fine art and experimental film and multimedia projects of Fluxus and others in New York and San Francisco later became reified into the big business model which dominates life as we know it today. I love this story partly because I see myself as having had a small role in it, being old enough to remember the time before the personal computer (my office at work is filled with mothballed Macs and PCs – I cannot bear to see them wasted) and the Internet, both played a crucial role in my development as an artist and as a filmmaker. But so did the myths of the 50s, 60s, and 70s anti-war- and anti-authority-driven countercultures. Where these two poles fuse and overlap and the points on the mind-map are many is where anyone who uses a computer and a camera should find a place for themselves, or risk living (in my view) outside of history.

When art and experimentation get big backing from the biggest players, the innocent art film, music, and computer freaks then have to leave town to let the big dogs piss all over where the artists once called their home. That once sacred place then reeks with the corrupted putrefaction of the purely commercially minded and Republican-backed military. That putrid reek now offends the whole world and has found its way into the cosmos itself.

If Kaszynski is not responsible for the horrors of a world gone mad with technological growth, he is painted by Dammbeck as that world’s most convenient scapegoat, the one who the whole time “told us so” whether or not we deserved to hear it, or indeed, risked getting killed by his bombs if we refused to. You don’t have to believe in technological determinism in order to condemn those who advocate its rapid and total removal in the violent way Kaszynski did. An utter impossibility anyway, as the hippies, the bushmen of the Kalahari, and the Amish alike have discovered. Better to forge an uneasy alliance and have your isolation with a bit of say, broadband, thrown in. Sacred isolation with a microwave oven. The Amish with his cell-phone (fact).

Seeing a film about the Kesey-led acid tests from someone who (I’m assuming) did not take part, and may in all fact have not fathomed the deeper, more subtle, cultural implications of this revolutionary set of gestures is like watching an up close and personal film about dolphins by someone who does not swim, nor sees the need to. It is thus based on a kind of bad faith that somehow this point does not matter, and most offensively to me, should not.

I think the film holds itself together extremely well as a film, is well made with a kind of knowing self-reflexivity (lots of shots of the laptop screen of QuickTime movies playing) and in parts very playful and deeply insightful as to the broader socio-cultural results of a lifetime of post-war technological changes which have led to the globalisation of Western Hegemony.

Das Netz revisits very, very familiar ground for those historians and media archaeologists like myself who have a vested interest in keeping the story “clean,” in which the good guys (artists, philosophers like Leary, Brand, Weiner, Fuller) are on one side and the bad guys (the evil CIA, the US Military, project MK Ultra et al) are on the other. Das Netz reveals that the truth could easily be that the two sides of the art-freak/CIA coin are really not so easily separated after all. Like the complementary opposites of the yin/yang, there's a piece of the dark side in the light, and vice versa. Better to understand this most bitter home-truth late than never.

What is ultimately most fascinating at the end of the day about Das Netz is the way in which it so carefully makes its connections between cold-war-space-race-LSD-cybernetics-ARPANET-counterculture, without ever claiming (as most US documentary filmmakers would) or declaring any emotional or political stakes in the views or aims of that 1960s counterculture. Most cyberpunks, freaks and computer geeks I know of my generation hold this period in such high esteem and know from deep inside something of this rich legacy to have already made these connections for themselves and to continue to do so to this day.

Others, like many I share Caltrain with in the bike car to Silicon Valley every day, could “totally give a shit” and read their Neal Stephenson novels and absolutely love money and the stock exchange and were right behind the dot-com period, and some even back the war in Iraq and willingly went to join the “war on terror.”

Maybe it is actually these people that need to see the film more than me, as it is their bad faith, which is today the problem and a very major one indeed, not Dammbeck’s and most certainly not mine.

David Cox, October 2005◊