Antonioni and Bergman are Dead: How's Cinema Doing?

15 Sep 2007

The summer 2007 deaths of European film directors Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman have gotten this writer thinking. Not so much about the directors, as about the changing role of cinema in our lives. Especially in the lives of college students.

Thirty or thirty-five years ago, intelligent urban college students cultivated cinema literacy. Members of this film-drenched generation include filmmakers Spike Lee, Ken Burns, Craig Baldwin. Besides rock record albums, movies were the medium discussed, analyzed and argued. Everybody felt they had a movie in them, and rock stars with money to burn (Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon) expended it on forgettable attempts to express that.

One undergraduate semester I managed to attend a movie somewhere every night. Very rarely were these first-run films, for the responsibility was to look backwards, watch older and/or foreign films, which had a greater legitimacy. Kurosawa, Resnais, Buñuel, Pontecorvo, Sam Fuller. Jodorowsky, man. There were careening, cartoony baroque visions coming from Europe, Federico Fellini's hearty, populous populism and Ken Russell's rockstar glam (casting Oliver Reed as Dante Gabriel Rosetti, or barking "But TOMMY doesn't KNOW what DAY it is...!"). Because Susan Sontag wrote an essay saying everybody should, another art student and I sat through an eleven-hour showing of Hans-Jugen Syberberg's "Our Hitler". Old chestnuts were resurrected, slight movies of the past imbued with historical significance; New Line Cinema was built upon Robert Shaye distributing "Reefer Madness" to campuses for Friday night laffs. About a dozen years ago, Quentin Tarantino updated the cineaste's aesthetic with a video-store literacy that showed in his own films as well as his Rolling Thunder Cinema re-issues. Yet how many bothered to go to a theater to see his "Grindhouse"?

One undergraduate semester I managed to attend a movie somewhere every night. Very rarely were these first-run films, for the responsibility was to look backwards, watch older and/or foreign films, which had a greater legitimacy. Kurosawa, Resnais, Buñuel, Pontecorvo, Sam Fuller. Jodorowsky, man. There were careening, cartoony baroque visions coming from Europe, Federico Fellini's hearty, populous populism and Ken Russell's rockstar glam (casting Oliver Reed as Dante Gabriel Rosetti, or barking "But TOMMY doesn't KNOW what DAY it is...!"). Because Susan Sontag wrote an essay saying everybody should, another art student and I sat through an eleven-hour showing of Hans-Jugen Syberberg's "Our Hitler". Old chestnuts were resurrected, slight movies of the past imbued with historical significance; New Line Cinema was built upon Robert Shaye distributing "Reefer Madness" to campuses for Friday night laffs. About a dozen years ago, Quentin Tarantino updated the cineaste's aesthetic with a video-store literacy that showed in his own films as well as his Rolling Thunder Cinema re-issues. Yet how many bothered to go to a theater to see his "Grindhouse"?

We could make our own movies too. Super-8mm movies were affordable, though limited. The VCRs and camcorders of the 1980s further put moviemaking and movie libraries close at hand. Alternative filmmaker Stan Brakhage came to my college and groused that its film library didn't even have 8mm Blackhawk Films (available in K-Mart) versions of historical classics. We gobbled up the collaged visions of Stan Brakhage, Bruce Baillie, Scott Bartlett and Bruce Conner; respected the kooky camp romps of Jack Smith and Andy Warhol in New York and the Kuchar brothers in San Francisco; and saw the dawn of rock videos in Kenneth Anger's combinations of both those collaged and camp strains.

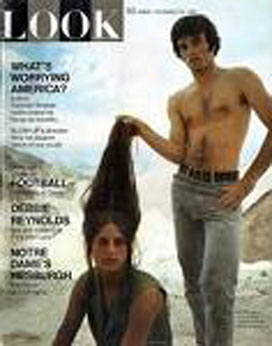

Antonioni's "The Passenger" featured Maria Schneider and Jack Nicholson (and inspired a bouncy song by Iggy Pop) but sticks in the mind mostly for its desert longuers. His "Zabriskie Point", featured Daria Halprin and a carnal-political climax that had consumer items like full refrigerators or Wonder Bread exploding in slow motion, while the soundtrack played Pink Floyd's screaming "Careful With That Ax, Eugene". This was a stoner's movie, which prompts today's skeptic to wonder if it could be enjoyed without psycho-chemical enhancement.

Antonioni's "The Passenger" featured Maria Schneider and Jack Nicholson (and inspired a bouncy song by Iggy Pop) but sticks in the mind mostly for its desert longuers. His "Zabriskie Point", featured Daria Halprin and a carnal-political climax that had consumer items like full refrigerators or Wonder Bread exploding in slow motion, while the soundtrack played Pink Floyd's screaming "Careful With That Ax, Eugene". This was a stoner's movie, which prompts today's skeptic to wonder if it could be enjoyed without psycho-chemical enhancement.

Bergman's "Virgin Spring" built suspense like a cowboy movie, as the viewer knows the stone-faced farmer will have vengeance upon the two vagabonds that raped and murdered his daughter. "Seventh Seal" featured a pageant in silhouette that included the Grim Reaper, and the man he came for trying to beat him at a chess game and preserve his own life. Both films, like Bergman's others, were well-made, deep, ponderous. But in college, I didn't appreciate slow.

Perhaps elitist high-culture trappings have fallen away from the cinematic medium, destroyed by the mergers that began in the 1980s, capitalism's inevitable consolidation. At that time, one writer lamented that the biggest movie producers of the 1930s and 1940s were rapacious businessmen but loved movies, whereas in the Reagan era and beyond, the accountants that run the studios don't give a hoot for the films. Perhaps the entertainment-consumer octopus has deadened interest, when every cereal box sports the latest Shrek (or this summer, Simpsons) imagery to remind you to buy buy buy. For twenty years TIME magazine has always managed to feature the latest Warner Bros. film rather than labor strife anywhere in the world. The backers of the prestigious films in Susan Sontag's canon may have been just as venal, flinty-eyed and out to make a buck, but they didn't have Rupert Murdoch's international clout. They were carnival barkers, not Thought Police.

Yet this is the best time ever for film buffs and budget filmmakers. Darn near every movie is available on DVD or VHS. Internet Movie Database (www.imdb.com) provides essential historical information, further Googling a raft of opinionated commentary. I've known current art students who say they want to make movies, but don't realize the old camcorder in their parents' garage is one place to start. Digital technology makes massive spectacles possible, and clever personal expressions of all kinds easily affordable. A filmmaker can make DVD copies for distribution of her work on her own computer. We can make movies with cell phones, and post them to YouTube for an immediate audience. Admittedly I spend more lunch hours in my office watching pop music videos there than seeking capital-A Art in the Antonioni and Bergman traditions. MTV at its best, and now YouTube, have helped showcase some cinema aesthetics of a century ago: contemporary films that evoke the Lumière brothers' shorts of everyday delights like workers leaving a factory, the hokey fun of Georges Méliès' "Trip to the Moon", Windsor McKay's hand-animated "Gertie the Dinosaur" cartoon. Now everyone can do cinema...though not necessarily well.

This sumer I've spent some evenings on a committee to review submissions to a local film festival, and while I'm seeing impressive competence, I'm seeing little that I haven't seen before. Is there less motivation to create something new, express something yet unseen, than to demonstrate genre skills in order to get a toehold in the entertainment industry? Is the proportion of careerists to artists any larger or smaller than in past decades, when the cost of entry (equipment) was so much larger? The guy in my college film society who talked most about foreign cinema and art ended up part of an entertainment conglomerate, and when he finally got a chance to direct, he made a loud, lame comedy that felt just like a TV sitcom.

Maybe Antonioni and Bergman left this world in peace, each contented at creating a body of movies the old way, at great expense and co-ordinated effort. Maybe they felt they were dinosaurs, from a previous era. I guess we don't know if Antonioni and Bergman are rolling over in their graves.

Mike Mosher has notebooks brimming with ideas for movies he hasn't found time to make.◊