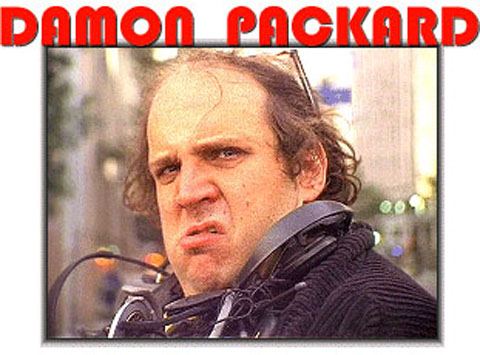

Sensurround Stardust in his Eyes: The Edgy Film Essays of Damon Packard.

13 Mar 2008

Damon Packard has some major issues with the state of contemporary filmmaking. He is that rarest of creatures in today’s independent film scene, a talented and hard-working filmmaker with a solid understanding and knowledge of world cinema history. Packard’s is a brand of film critic-turned-maker which, like that in France 45 years ago, is borne of the Los Angeles Cinematheque, a childhood in front of the glowing TV––the film-buff as student of history.

The possibilities of filmmaking as they presented themselves to anyone wise enough to capitalize on them at the time (e.g. Spielberg, Lucas, Coppola et. al. ) were so obvious that the whole industry was ‘just there’ for the taking. All you needed was to seize the new portable cameras and recording gear, convince a few ‘hip’ producers you had what it took, borrow heavily from the Europeans, and make your film as if you were Godard or Visconti working in California instead of Paris or Rome. Lots of soft-focus, lots of inner monologue/dream sequences a la Bergman, lots of long takes like Bresson. Then you apply these techniques to ‘renovating’ old 1930s genres like Space Opera, and the Jungle Adventure.

In the intervening years, partly because of the initial success of these 1970s ‘pioneers’ (especially George Lucas), the entire contemporary media production industry is a vast and relentless ocean of vested commercial interests, concentrated imperial power, and complete top-down hierarchical control of every single aspect of mainstream entertainment.

Whatever vague liberal/left-wing agenda the likes of Gary Kurtz and Monte Hellman and Roger Corman were willing to give lip service to back in the early ‘70s, the successes this group gave witness to have all but extinguished that same hip libertarianism completely.

Rather, today the Indie spirit is in a kind of nexus between the angst of post-9/11 Pax Americana, mixed with the darker visions of the 1970s as talismanic set of signifiers––Mansonesque madness, bad trips, and Nixonian collapse of the body politic.

Makers can intensify the ‘feel’ of former periods, by using digital tools to revisit the mythology of those mythical times. Call it Psycho-Drama with Final Cut Pro. It’s like the band Stereolab recycling design-centered early 1970s Euro-Pop and updating for the era of Pro-Tools and mp3.

Packard’s filmic devices include the liberal uses of modern tools of movie distribution that in 1975 would have sounded like something from the mind of sci-fi scriptwriter Dan O’Bannan––a vast international system of storing movies, available to anyone connected to see them and contribute to them in turn. YouTube, Peer2Peer, and the sneakerware stealth-delivered DVD are Packard’s methods of getting his work seen, and it is slowly but surely working.

For Packard and the rest of us struggling Indie filmmakers with a brain, the stakes are high and the opponents strong.

For the overarching domination of today’s stupefying massive media empires extends into every aspect of life. This awesome power of vision, sound, and software is buttressed and defended by the most powerful institutions on Earth. The military-entertainment complex, for want of a better phrase, is no less that that which maintains a viciously protective force-field around any kind of production which might conceivably be converted into money and power. To make films which criticize this system is to invoke its merciless wrath, as Welles did with Citizen Kane when he took on William Randolph Hearst, and paid with his career from then on as a result.

Packard is very much like Welles. He is exiled from the studios which he honestly and justly believes he should be allowed into. He knows all about their modes of production and exploitation. Enough to easily occupy a seat of power were one somehow made available to him. He would be a kind of cross between Roger Corman, Orson Welles, Ed Wood, and John Waters were he to find himself one day in a position of director or producer.

But, as with Welles again, ironically, it is Packard’s very knowledge of the origins of modern cinema that are so dangerous to his career. He knows simply too much about how the tiny handful of people of once-upon-a-time-wannabes-in-the-early-1970s  who run Hollywood got there. "Reflections of Evil" shows a young Steven Spielberg haplessly trying to get his old-fart crew to do as he says, an event that is well-chronicled in any Spielberg biography. As the young director throws stunt-dummies around to communicate what he wants, everyone just looks on, bemused, cast & crew alike. Just as it once was for the young wunderkind , Packard too now must endure the indifference of an establishment that he feels he has every right to join, which simply does not get his genius.

who run Hollywood got there. "Reflections of Evil" shows a young Steven Spielberg haplessly trying to get his old-fart crew to do as he says, an event that is well-chronicled in any Spielberg biography. As the young director throws stunt-dummies around to communicate what he wants, everyone just looks on, bemused, cast & crew alike. Just as it once was for the young wunderkind , Packard too now must endure the indifference of an establishment that he feels he has every right to join, which simply does not get his genius.

Packard’s appeal to us in the realm of "other" cinema, (his real audience), is enacted through performative gestures like the massive DVD give-away project of self-distribution which has all the hallmarks of a noble potlatch sacrifice. "Look at me" the gesture says; I can make films which chronicle the tragedy of their own lack of attention by the people who matter!!

Packard is once again really, actually, like that young Spielberg––desperately trying to convince all around him of his undeniable technical and cultural talent, but to the deaf and uninterested around him, he’s just an annoyance, something in the way, like a crazy person who talks to himself at bus stops. His character of Bob is confused at the fact that nobody wants to buy his cheap watches.

The watches are tainted objects, since Peter Fonda took his off in disgust in "Easy Rider", the marginal class in California has had little use for them, at least at the street level, where time is measured in periods between cheap meals, places to crash, avoidance of cops, fifths of booze, doses of crack, smack, meth, and tobacco.

Only those with any kind of purchase on their own lives need watches, so trying to sell them to the dispossessed and homeless of the areas around Hollywood is a pointless exercise. Bob naively keeps trying though, and keeps returning to his screen to gorge himself on sugar to keep his outrage and his blood pressure up.

It is as if the dreams of the immediate post-Counterculture period were washed ashore as so much flotsam and jetsam, along with the visible results of 40 years since of active campaigns by the right-wing in the USA, to destroy all traces of that period, all hints of the benefits the ‘70s brought with them, such as self-awareness, an understanding of the world as a place, the mind as a temple, of drugs as a means of enlightenment, of the American Republic as a site for public imagining.

Reagan, Clinton, and both Bushes’ economic policies have turned the once-vibrant, happening inner-cities into wastelands of contained madmen, homeless, drug-addicts, and wanderers, whose only crime is to be alive, poor, and living in America. Packard’s Bob is the fat and borderline fool who, like ancient Rome’s stuttering Claudius, knows more than he lets on, and sees in overhead contrails, the lateness of depended-upon buses, and the constant assaults by the victims of the streets, evidence of his own spiritual and physical demise. These are the ‘reflections’ of an evil, which is as deliberate and intended as any planned for and funded freeway overpass. The myriad casualties of peace of modern urban life become in Bob’s mind interfused with the many characters from science-fiction set in Los Angeles. People mutter lines from Blade Runner, Logan’s Run. The streets themselves have the late-afternoon orange sun of many a disaster film. George Kennedy and Charlton Heston could appear at any moment to declare their moral outrage.

This is the Los Angeles of Mike Davis’ "City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles”.

Wikipedia has this to say about this book:

"The book is a Marxist historical, economic, and cultural dissection of Los Angeles, its residents and their lifestyles and their interactions with real-estate developers. Davis contrasts the campaigners for ‘slow growth’ with the needs of minorities living on the margins and the never-ending growth of Los Angeles with environmental considerations."

Other Packard films, like his "Untitled Star Wars Mockumentary”, albeit about a Bay Area mogul, are no less critical for their condemnation of what he sees as the corruption of so much money being spent on so many people to make so mediocre a film as the episodes I through III of the digital-age “Star Wars” saga.

Other Packard films, like his "Untitled Star Wars Mockumentary”, albeit about a Bay Area mogul, are no less critical for their condemnation of what he sees as the corruption of so much money being spent on so many people to make so mediocre a film as the episodes I through III of the digital-age “Star Wars” saga.

When pop culture ‘does’ the 1970s, it is more often than not to sneer knowingly and condescendingly at the supposed ‘excesses’ of style which predominated then. Hipsters swarming about the renovated downtowns of today, toting laptops and lattes, generally do not wear or espouse the culture that their equivalents did at the time; rather, they sport the cheesy slacks, wide lapels, big sunglasses and sideburns that were actually the realm of the straight world in, say, 1972.

The politically astute then made clothes, or found them, and generally avoided the polyester styling that was favored by those that purchased items from chain stores.

Similarly, the look of mainstream TV and cinema was also infused with the residual drip-down effects of the Counterculture. It was common for themes about drugs, sex, and leisure to predominate on the screens at the time.

Experimental film had infused most aspects of screen production with its telltale emblems – liberal use of lens filters (to suggest ‘trips’ or madness), shaky, handheld camera, allowing ‘mistakes’ like lens flare to create dreamlike effects on film. Hippies had opened the door for filmmakers to try anything, and, given the rapid and irreversible collapse of the traditional film-production studios, more and more experimentation was possible.

This is the world of filmmaking that Damon Packard seeks to evoke with his modern masterpieces, done today with a myriad of formats, and generally edited with Final Cut Pro. Packard ‘samples’ the period, borrowing fragments of camera style, actual snippets of audio and music, and creating an alternative cinema of the 1970s for today.

It matters not a toss to him what is copyright and what is not, for, like the Situationists, he knows that the pressures of today require drastic measures. Outright copying of Carpenters’ songs, THX sound effects, and just about everything else, is the only way to close the gap between oneself and the rapidly approaching missile of copyright, such that the destructive device will arm then explode itself before it reaches its target, not expecting that target to actually run toward it!

“Reflections of Evil” is, to me, Packard’s absolute masterwork. This unhinged and sad portrait of the city of light from the very depths of its broken streets, betrays a Diane Arbus’ like familiarity with its outcast subjects. It vividly evokes the mythos of Los Angeles filtered through a thousand movies, and a thousand actual walks and drifts through her streets.

"Reflections" also bespeaks a real insider’s knowledge of that city’s dense multi-layered patinas of myth, magic, and darkness. Packard walks where Jim Morrison once did, alongside Bruce Conner, and Rick Deckard from “Blade Runner”.

It’s fitting that his “Star Wars Mockumentary” tears such massive satirical shreds from the digital-film cult, which has taken over contemporary film production of sci-fi fantasy. Packard, like many of us, is enamored of Lucas’ early work, films like “THX1138”, which were directly inspired by the experimental photo-collage and audio collage films of Arthur Lipsett and Bruce Conner. All the more outrage he feels at the betrayal of Lucas, as bad as anything his Anakin Skywalker alto-ego ever pulled off, turning to the dark side away from the experimental underground and into the dead end of mainstream commercial shopping-mall mass entertainment.

Like many old enough to have seen the release of the first “Star Wars”, and to have known from the inside the links between this film and these earlier, more radical inspirations from which it emerged, I can harbor some resentment for Lucas and his decision to devote his life to building a monumental edifice of modern pop religion, rather than simply use the ‘Force’ and wing it with more and more experimentation. Instead of Lipsett-a-likes, we got “Howard the Duck” and “Jar Jar Binks”.

Thus, it is because the original “Star Wars” and “THX1138” were as close in spirit to the 1970s ‘golden age’ of experimentation, borrowing closely from the conventions of European hand-held verite , action-cutting of the sort associated with Godard’s “Breathless", that the fall from grace seems so total. Such once-stalwart supporters of experimentation like Lucas simply ended up commanding entire vast armies of digital specialists, turning the creative process into yet another mind-numbing industrial process of the sort the Zoetrope boys tried to overturn. This signals a betrayal so deep to Packard that only a broadside of the venom of “Untitled Star Wars Mockumentary” can come close to symbolically settling the moral score. This is how much Packard cares about this issue. He takes it hella seriously, dude.

In "Untitled Star Wars Mockumentary", Lucas is framed as the madman Colonel Kurtz in the jungles of contemporary film production, talking about digital characters that "you don’t have to stand there & shoot ... ". Packard and his friends insist to George (intercut into the DVD’s ‘making-of’ material of production meetings)––"we can’t do it for the budget, George!!", echoing stories that there were mass exoduses of staff following the crushing schedule which attended the pre-release of "Phantom of the Menace". Lucas’ staff grin and bear his demands for realism, and an intercut Packard and his colleagues grow impatient with the auteur, finally lashing out with "WHAT THE FUCK DO YOU WANT US TO DO????"

Back to the Future of “Reflections of Evil”: As in "Chinatown", the corruption runs so deep in LA that to hold out any hope for people’s good intentions is as fruitless as, say, trying to sell a cheap watch to a crack addict wielding a hatchet!

Packard’s Los Angeles, for all its brightly lit oppression, is somewhere, somehow, redeemed ultimately by all the films set there. Average people start talking about ‘Taffy Lewis’––a minor character from “Blade Runner”, others knowingly refer to Speilberg’s early days as a wannabe at Universal Studios, hopelessy trying to convince his older crew that he has what it takes.

“Reflections”––a film I could not stop thinking about for days after seeing (only “Taxi Driver” and “Eraserhead” had that effect on me prior) is about the strength it takes to just focus on any kind of meaningful activity at all when so much of the cultural landscape of the city of Los Angeles is so deeply and staunchly enmeshed in the countless iterations of its screen-based self. So many Los Angeles visions appear before the visitor, who has literally seen so much of the city on TV and film that it feels like home long before you step foot there.

Packard’s Bob is both the visitor from TV-viewing land, as well as the average Sunset Strip freak who is trying to get by with a scam like everyone else. Bob’s multiple earphones dangle about his head, as if no number of them could ever present the city’s true sound. Real movie directors listen to location sound as much as they lens the city in front of them with view-finders, so the headphone is more than an emblem of the Walkman/iPod-wearing citizen, it is the signifier of the director-on-the-loose. Packard is his own director, not knowing which set of headphones to listen to, as the soundtrack to the bedlam around him deafeningly obliterates any other audio cue which might give him purchase in his world. Waiting for the bus, like a never-appearing Godot, is as much a task as getting a film financed, seen, and appraised. Packard is the Aristotle of the LA film underground, wearing the truth of his philosophy like a cheap suit, proudly embodying the essence of a life made of film and of films made of life.

Packard’s Bob is both the visitor from TV-viewing land, as well as the average Sunset Strip freak who is trying to get by with a scam like everyone else. Bob’s multiple earphones dangle about his head, as if no number of them could ever present the city’s true sound. Real movie directors listen to location sound as much as they lens the city in front of them with view-finders, so the headphone is more than an emblem of the Walkman/iPod-wearing citizen, it is the signifier of the director-on-the-loose. Packard is his own director, not knowing which set of headphones to listen to, as the soundtrack to the bedlam around him deafeningly obliterates any other audio cue which might give him purchase in his world. Waiting for the bus, like a never-appearing Godot, is as much a task as getting a film financed, seen, and appraised. Packard is the Aristotle of the LA film underground, wearing the truth of his philosophy like a cheap suit, proudly embodying the essence of a life made of film and of films made of life.

He is like Godard, Herzog, and Wood rolled into one.

“Reflections of Evil” occupies a similar terrain as David Lynch’s “Eraserhead”. In that starkly brutal appraisal of how American cities can stand in for the mindsets of the insane, the 1930s Deco bridges and brick Functionalist ex-factories combine in that film to externalize the steady nervous collapse of Henry Spencer. “Reflections” is also cut from the same cloth as the old Mack Sennett "Keystone Kops" shorts from the ‘30s, in which everyday L.A. is just ‘there’ in the background, while lunatic sped-up chaos unfolds all around. Authority, long gone, is left to catch up with itself amidst the dust and light of a city unwilling to give up its own secrets to just anybody.

Bob can only eat himself into submission under the pressure of simply dealing with what the streets have to offer. The sun-drenched inner-city Los Angeles offers only one insane person after another, each of whom have rejected everything. They happily smash their heads against the pavement, spew blood and bile, and are thrown about by the unseen forces that toss murderer, hooker, film producer, and homeless men into the same arena.

Michael Mann’s "Heat" showed us an amped-up, brightly-lit gunfight in the middle of the streets of LA, and as the shooters stumble about in an ocean of shell-casings and shot-up cars, that same sun beats down on skyscrapers and passers-by alike. Packard’s Bob would not be out of place during such scenes, attracted to violence and the product of it.

Excess, the sort that drives fat men to gorge themselves on massive bowls of cereal while watching 70s TV in an attempt to connect with a more creative time, takes its toll. Bob’s appeal is for them to buy a watch; after all, even a crazy person needs to tell the time. No they don’t. These people and the place they are in are really outside of time, as is Bob, stumbling about among them. His struggles with sanity match those of the history of mainstream TV and cinema, which is littered with the remains of those who made it, those who didn’t, and those who never cared.

Los Angeles is the brightly-lit oasis of fear which attracts and repels. Tinged with shit, piss, menace, and danger, the streets around Universal Studios can only be met with the opposite force both inside and outside its gates––we might call it Packard’s Sensurround Stardust Sensibility.

David Cox, March 8th 2008

David Cox is a writer, filmmaker, and artist who lives in the Mission District of San Francisco. He is a regular contributor to OtherZine.

◊