Is It True That We Enjoy Nothing?

5 Sep 2009

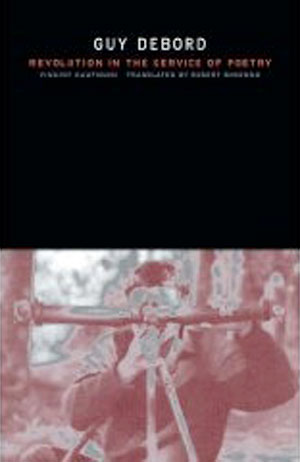

Vincent Kaufmann. Guy Debord: Revolution in the Service of Poetry. Translated by Robert Bononno. University of Minnesota Press, 2006, 384 pp.

"In a world that is really upside down, the true is a moment of the false." --Guy Debord

Like that of any great poete maudit (oops pardon my French), the imprint and influence of Guy Debord is difficult to truly trace or adequately represent. To begin with, the situations that came about as a result of his activities in the latter half of the twentieth century are basically, well, unspeakable. Furthermore, the guy not only vehemently disapproved of any attempts at second-hand accounts of his life or work, he also managed to leave behind precious few documents detailing the facts of his daily existence (documents from which one might now expect such accounts to be constructed).[1]

That's not to say that there hasn't been, in the last fifteen years, an insane proliferation of English-language material on matters related to Debord's biography and its significance. But whether this heap of new literature has served to untie any lingering practico-theoretical knots, not to mention whether people currently are in any position to absorb the old man's insights and their full implications, is rather hard to say. Now, before we assess the stature of the work of this Vincent Kaufmann, let us rewind a little bit to review the writings and rants of some of his predecessors (and their critics).

A certain Len Bracken (psychogeographer, son of a federal intelligence agent[2], former editor of Extraphile) once claimed (falsely?) to have written the first ever[3] biography of Guy Ernest Debord. Bracken's scrappy (and slightly rushed) tome, Guy Debord-Revolutionary was fairly well received in its day (1997) by one John Zerzan. In the pages of Journal of Desire Armed, that now-famous primitivist called the volume "most substantial," despite also pointing out that Bracken's wording can be a bit "clunky," and noting too that his explanations are built on mere "thumbnail" sketches of some rather complicated matters. Meanwhile the reaction of Bill Brown (Surveillance Camera Player, alleged creep, editor of Not Bored) to the book was mixed: he wrote a couple of nice bits about it, but also complained that Bracken had not bothered to personally interview anyone who'd been close to Guy Debord (or really anyone else for that matter). Bracken, in turn, somewhat strangely (though, I think, notably) responded to Brown's comments by going into detail about how the much-lauded work of Greil Marcus (Brown's supposed mentor) succeeds primarily in "obfuscating" the views of the Situationist International (S.I.). Brown also claimed that his own sober and functional "exposition" of Debord's life and times should prove more useful (to "budding American radicals") than much of the heady intellectual hair-splitting of a certain European Marxist: Anselm Jappe.[4]

A dense and formidable contribution to the field, Anselm Jappe's Debord appeared in English in 1999. It's characterized largely by its lack of anything resembling a sense of humor. Now, for anyone curious about, say, the importance of the theories of Georg Lukacs--whose writings from the 1920's would serve to push Guy Debord into penning a unique re-explanation (during the 1950's) of Marx's ever-important concept of "commodity fetishism"--Debord is, admittedly, where to look. However, for anyone wondering about, say, what kind of food Debord would eat after a very long drunken walk through Paris,[5] Jappe's effort leaves something to be desired. This is not to suggest that Jappe's intention was ever to write about Debord's day-to-day adventures: it wasn't. This is only to point out that details of such adventures, for the average scholar or would-be revolutionary, remained relatively hard to track down even five years after Debord's death.

Enter Andrew Hussey. His (2001) biography of Debord, Game of War, was at one point praised in a review (in the UK's Guardian) as having a load of new information about Debord's life. Indeed, Hussey seems to have tracked down a number of solid interview subjects in the course of his research--both of Debord's former wives among them--and this no doubt resulted in the inclusion in his book of myriad little sketches and anecdotes that one would (maybe) be hard-pressed to find anywhere else. It is here that Jacqueline de Jong[6] is at one point quoted, describing Debord as "always pushing forward...with his fat belly...like an arrogant little plum pudding." And Hussey elsewhere shares information about a little-known (and ill-fated) Situationist business venture: a bar and night club, which they called La Methode. The author delivers some juicy tidbits, too, on some shady peripheral Lettrist figures such as Pierre Fouillette: "[Debord's] principal kif supplier ... [supposedly] had half of his ear torn off in a knife fight (it was actually bitten off by a girlfriend)."[7] One also learns from Game of War a few things about Eliane Papai: a wild delinquent, Debord's one-time ladyfriend would eventually marry the Lettrist Jean Brau and then later was accused (with Brau) by Debord (and co.) of "falsifying" information regarding the momentous events of May 1968.[8]

It is worth noting here that Alice Becker-Ho and Michele Bernstein (Debord's aforementioned spouses) would both ask, upon its completion, that Andrew Hussey's book not be published. Becker-Ho, we might also remember, would go on to call ol' Bill Brown a "sad clown" or something or other when he insisted on autonomously organizing a naughty (unauthorized) exhibition--in New York City--of every single one of Guy Debord's films. Which was funny, if only because no one even bothered to go to the screening anyway.

Despite his now being fairly recognizable name here (having appeared, in animated form, in a Richard Linklater film, not to mention being a sort of godfather to the whole Adbusters set or whatever), Guy Debord's accomplishments seem to be sorely under-appreciated by America. This is perhaps because 1973's Society of the Spectacle (Debord's masterpiece, and arguably one of the most relentlessly subversive films ever made) has only rather recently been made available in an overdubbed English-language version. (That's right, thanks to San Francisco's Konrad Steiner we can now happily take in the visuals without being expected to simultaneously read Debord's entire text in subtitle form.) Though also unauthorized by Becker-Ho, Steiner's release stands, I think, alongside the recent output of McKenzie Wark and Tom McDonough, as one of the more significant Debord-related resources that have been made available so far this century. Speaking of which, let us now return to Revolution in the Service of Poetry.

It is in the first section of Vincent Kaufmann's 2006 text that the writer lays the groundwork for what is apparently his favorite theme: that of Guy Debord as "lost child." This approach at first comes across as compelling and unique but soon gives way to excessive, pointless, meandering iterations of the "lost child" idea. The author simply waxes too philosophically, and for too long: "where do lost children come from?" / "the lost child remained faithful to himself and to loss?," etc. The result is that, here, as with the rest of the book, much of what Kaufmann seems to consider insightful just falls flat and serves to take up space.

But, this isn't to imply that the book, or even the first section, is a flop. Kaufmann is a professor of literature (in Switzerland), so, one ought not really be surprised that his writing is sometimes fatty or fluffy. (Some of the wordier passages in fact seem to be downright useless.) The presence of such academic drivel in this book though doesn't necessarily detract from Kaufmann's overall portrayal. Kaufmann seems honest enough. And, in a way, he could be praised for keeping the book as short as it is, given the extraordinary amount of different territories into which he (often rather skillfully) drifts.

The book is just about equally divided into three parts: first Debord's experiences as a Lettrist (including his falling out with Isidore Isou[9] ), then the various phases of the Situationist International (architecture and urbanism, then rejection of art, then "communication" and all that), and finally Debord's stint as the clandestine anti-celebrity of the 70's and 80's (during which time he was apparently considered a bona fide terrorist threat in several European countries). In general the book's method resembles that of any literary biography--even while it acknowledges the problem of seeing Debord as a purely literary figure. (One might observe that it also sometimes psychoanalyzes Debord even while calling attention to the shortcomings of psychoanalysis as a discourse).

Ken Knabb, the primary American translator of Guy Debord's writings, has said that Kaufmann's account of Debord is strong on the cultural end but weak as far as politics is concerned.[10] Well, we have here Debord the lover, Debord the poet, Debord the conversationalist, Debord among friends and rivals. We see him at home, in hiding, in transit, in the press, and all throughout his adult life (up until his suicide in 1994). Overall Kaufmann's is a rich and careful portrait--which places the man in various categories without failing to point out the lameness of such categories. Debord, quite an enigmatic figure, went out of his way to denounce the vagueness and inaccuracy of many commentators who tried to encapsulate or criticize his ideas during his lifetime. (As he once said, "I am what I am, my image belongs to me.")

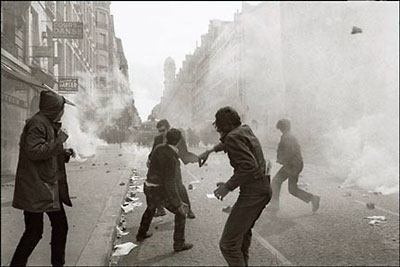

Kaufmann clearly admires what Debord accomplished. Not only does the author tend to avoid placing his Guy on the same plane as various rivals and peers and teachers (Castoriadis, Lefebvre, Godard, Lyotard), Kaufmann even spends a bunch of ink at one point arguing that it is not unwarranted to call Guy Debord the 20th Century's Jean-Jacques Rousseau! The tendency to refuse to make Debord "take his place" amongs his contemporaries is not uncommon among Situ scholars, who sometimes seem to point to the S.I.'s influence on the historic happenings in Paris in May 1968 as proof of their heroes' unique importance and transcendent status in relation to the whole post-War "Outlaw Industry."[11] Len Bracken somehow explicitly admits to basically being at Debord's service (despite also claiming to have taken an "objective" and non-emotional stance on the various issues under examination). Knabb too continues to praise Debord to no end, sending out email bulletin after email bulletin, from his little backyard cottage in North Berkeley out to anyone on earth who will listen.

No doubt there are many who will listen. It has been stated time and time again that--whether or not he was an asshole--Debord's theses are as brilliantly relevant today as they were when originally conceived. An expert strategist, Debord seemed to view the entire world as his chessboard (though he apparently never traveled outside of Europe). He was, no doubt, quite able to think many moves ahead of his various, numerous, opponents; and this is perhaps what ensured that his work would age as well as it has. Daniel Blanchard, who was partly responsible for briefly bringing Debord into the fold of the group Socialism or Barbarism[12], has asked: "How is it...that my excitement of some 30 years ago, when I first discovered the S.I., is still tingling--not as some narcissistic pleasure in reliving the vanished past, but truly as the ongoing perception of an invaluable uniqueness?" He went on to answer: "It is, I believe, because of the sense of form...that inhabited everything Debord undertook, and contributed enormously to making him effectively subversive."[13]

More than a few noteworthy questions are raised, or put to bed, in Revolution in the Service of Poetry. We will examine some of these briefly below.

2. Kaufmann, to his credit again, rebuffs those who--based on criticisms of Debord's controversial habit of "expelling" various associates--have mistakenly characterized the man as a "Stalinist." Kaufmann defends the divorces in question (some of which were actually amicable and/or mutual, it should be noted) and explains how important they were in the ongoing process of defining the Situs' ever-precisely pruned points of view. The expulsions, arbitrary and irrational as they may have sometimes appeared, were not, Kaufmann maintains, "pathological.

3. The author provides a good deal of clarification regarding the para-political atmosphere in which the assassination of (Debord's trusted friend and associate) Gerard Lebovici took place. You won't find any speculation in this essay as to what went down. I will note only that readers who wish to read more about the conspiracies that took place in Debord's later years may find the recent, readable, work of Andy Merrifield to be a somewhat useful companion to Kaufmann's descriptions of that period. (And, while you are at it, perhaps also take a look Len Bracken's essay "The Spectacle of Secrecy.")

4. There is, finally, one might think, the question of depression. Debord killed himself. His wife at the time would later call it a "noble" act. And elsewhere it has been stated that Debord's suicide had no "literary" significance--in other words, he was not trying to "say" something, he was rather quite simply putting himself out of a misery brought on by excessive drinking. OK but is it uncalled for to ask whether Debord qualifies as having been "clinically" depressed?[14] And then also, to what degree were his "revolutionary" activities effectively therapeutic? The issue of Debord's emotional state does not escape Kaufmann, who asserts that there was a "weighty burden of melancholy associated with [the point of view of Debord's desire]" and then later asks whether "[love is] possible when someone is ? surrounded by a dark melancholy."[15] His answer to the latter question is this: "Certainly [it is possible], at least to judge by Debord, who seems to often used his melancholy to remain within the nexus of passion."

...Kaufmann of course goes on (and on). We could go on too: about love, about art, about utopia. We could tackle friendship and hospitality. Kriegspiel. Alcohol. Or even "lost children" again. But, my friends, McKenzie Wark and Stewart Home are right: there's really no need for new scholarly work on the Situationists. Anyone who wants Debord to rest in peace must agree: there can in fact be no Situationist scholarship, but only Situationist uses thereof. Fuck, who wants to read all this shit anyway? Let's go to the beach. I hear that there's one right around here, just beneath these paving stones.

◊

[1]One of his own autobiographical efforts infamously resulted in a book composed merely, and entirely, of repurposed quotations from existing books by his favorite authors.

[2]See Monty Cantsin's correspondence with Bob Black circa 2007 (which is all on file at a library in Ann Arbor from what I understand).

[3]Bracken, apparently, delights in being the first to finish. He would later boast about the primacy of his piece of 9/11 conspiracy research, Shadow Government. (Which, by the way, was favorably reviewed by the Village Voice (though the critic was baffled by Bracken's citing of an article in The Enquirer as a reference).)

[4] Let us avoid going into the Brown/Bracken exchange regarding Pierre Guillaume, fascinating as it may be. (Remember when Noam Chomsky got bamboozled, or something, around 1980, by that one Holocaust revisionist guy in France??) And we shall also avoid opening Bob Black's Big Can of Worms in the present essay--his response to Brown's reply to Bracken's take on Debord was most likely written only because he personally dislikes Brown. (Like his name was Arthur Cravan, Black no doubt considers a well-executed letter of insult to be a thing of rare beauty.)

[5]Salted anchovies. Or cheap Chinese.

[6] Editor of the Situationist Times (which was deemed by Debord to be an anti-Situationist publication), Ms. de Jong once described herself as maintaining a sort of "undercover" Situ-presence within a certain international fine arts milieu. According to Hussey, she was admired by Debord, but fell instead for Asger Jorn-one of the excommunicated artist-types whose split with the official S.I. group was peaceful.

[7]Hmmmm. Is his story about those Chinese corpses really true? (Where else has it been printed?)

[8]Gosh, Kristin Ross has written a whole damn book about the ways in which the events in question have been falsified by everyone-and-his-brother. ...Maybe you just "had to be there."

[9]The influence of Isou on Debord, Kaufmann claims, has been overlooked or underestimated by more than one biographer of Debord. Isou, who died only recently, was in fact the person who helped Debord find a room in Paris once the latter had moved away from his family in Cannes. It has been said that he was deeply hurt by Debord's later actions toward him.

[10](In conversation with Monty Cantsin at the 2008 San Francisco Anarchist Bookfair.)

[11]"Outlaw Industry" is a term invented by Timothy Leary. It first appeared in National Review circa 1977.

[12]Few seem to be aware of Debord's brief involvement with this group (which Anselm Jappe has asserted was the only "passable theoretical voice of independent Marxism in France" around the time of its founding in the late 1940s). It is notable in part because Debord apparently broke his own rule: membership in the S.I. was supposed to entail a withdrawal from all other collectives.

[13]Blanchard's one-time comrade, (the now notorious/discredited) Pierre Guillaume (--see above footnote), has summarized Debord's unique importance thusly: "In the same way that Marx's descriptions of capitalist society...separated from the perspective of the inversion of this society, doesn't bother anybody, Debord's description of the society of spectacle could only be mere lucidity. A lucidity...that is rare enough to bring him fame, but not sufficient to transform the world."

[14] The fact that Debord was (according to Andy Merrifield) an asthmatic perhaps warrants a mention here of Alexander Lowen's book Depression and the Body. Lowen's scholarship, influenced by Wilhelm Reich, posits some connection between depression and asthma.

[15]His lover Eliane Papai reportedly once said to Debord: "Guy, is it true that we enjoy nothing? I don't think so."

◊