The Blessing of Silence:

John Cage and Radio in the 1920s

Part 1

1 Mar 2012

Imaginary Landscape (1939), for records of constant and variable frequency, large Chinese cymbal and string piano, to be performed in a radio station

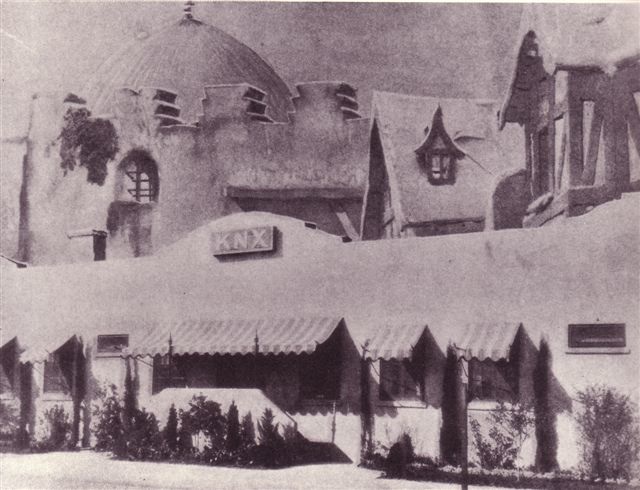

W ith his Imaginary Landscape of 1939, John Cage began integrating radio into his musical compositions. Imaginary Landscape, which combined a radio station's turntables and broadcast apparatus with piano and cymbal, was the first real success of Cage's career as a composer. But Cage's involvement with radio had in fact begun a decade and a half earlier, while he was still a child living in Los Angeles. Cage, at the beginning of his high school years, created and directed his own radio show on station KNX of Hollywood. The show, a sort of Boy Scouts' variety hour, started broadcasting around 1925 or 1926 and ran for two years.

Radio was a topic of some discussion in the Cage household, even before Cage joined the Boy Scouts and KNX. Recalling his years at KNX, Cage remarked:

Well, radio was very close to my experience, because my father was an inventor. He was never given credit for it, but he had invented the first radio to be plugged into the electric light system. (1)

If it is true that Cage Sr. had invented a radio powered by alternating current,(2) his invention must have taken place prior to 1925, the year when "all-electric sets" first became commercially available.(3) Perhaps the invention took place around 1921, the year that Cage Sr. filed his first electrical patent.(4) Cage Jr. would have been nine years old at that time. The fact that the father 'was never given credit' for his invention may well have been a sore subject in the years leading up to his son's involvement with radio.

It should be remembered that, as new technologies were transforming the world in the first two decades of the 20th century, a virtual cult of the inventor sprang up around such figures as Thomas Edison and the Wright brothers. Children's literature, especially books written for boys, glorified inventors and entrepreneurs. The fictional hero of a popular series for boys, Tom Swift, was a young inventor and entrepreneur idolized by millions of boys.

...[A]s new technologies were transforming the world in the first two decades of the 20th century, a virtual cult of the inventor sprang up around such figures as Thomas Edison and the Wright brothers. Children's literature, especially books written for boys, glorified inventors and entrepreneurs.

In retrospect, Cage Jr.'s life bears a certain resemblance to that of the fictional Tom Swift's. Cage, like Tom, was himself the son of a successful inventor. Of both Tom and Cage it could be said that their genius consisted not so much in inventing new technologies as it did in seeing untapped possibilities in the new technology being developed by others(5)(Cage's prepared piano, for example, was a "fixing" of techniques he had observed practiced by his teacher, Henry Cowell). Rather than employ the typical space-travel settings of contemporary science fiction, the Tom Swift books capitalized on the excitement generated by inventions that had only recently been introduced to the public.(6) As their titles indicate, the tales dealt with revolutionary improvements to recent technologies, especially technologies of locomotion and of mechanical reproduction. Thus,Tom Swift and His Submarine Boat, Tom Swift and His Talking Pictures, Tom Swift and His Wireless Message.(7) Each book showcased a new technology: motorcycles, electric cars, electric trains, submarines with advanced engines (something Cage Sr. had designed), cameras, talking pictures, wireless, and so on. The books, published from 1910 till 1941, reached the height of their popularity in the 1920s (8) and made Tom Swift a household name.

Rather than employ the typical space-travel settings of contemporary science fiction, the Tom Swift books capitalized on the excitement generated by inventions that had only recently been introduced to the public. As their titles indicate, the tales dealt with revolutionary improvements to recent technologies, especially technologies of locomotion and of mechanical reproduction.

The Swift books have rarely been taken seriously by literary critics, even as a species of children's literature, since their action-adventure plots were formulaic and their characterizations one-dimensional. Nevertheless, in the "objective" tone of their language, these works reflected a distinctly "modern" literary sensibility: Their style rejected the lush description of Victorian writers like Edgar Rice Burroughs (as too feminine?), in favor of the deliberately flat, denuded, and empirical tone of technical writing. This stripped-down aesthetic was undoubtedly meant to signal the heroic seriousness and objectivity of the scientist/inventor's world, while at the same time capitalizing on the reader's fetish of technology.(9) The following passage from Tom Swift and His Wireless Message (1911), is cited by the critic Francis Molson as an example:

"There was certainly plenty of machinery in the cabin of the Whizzer. Most of it was electrical, for on that power Mr. Fenwick intended to depend to sail through space. There was a new type of gasolene engine, small but very powerful, and this served to operate a dynamo. In turn, the dynamo operated an electrical motor, as Mr. Fenwick had an idea that better, and more uniform, power could be obtained in this way, than from a gasolene motor direct....There were various other apparatuses, machines, and appliances, the nature of which Tom could not readily gather from a mere casual view."(10)

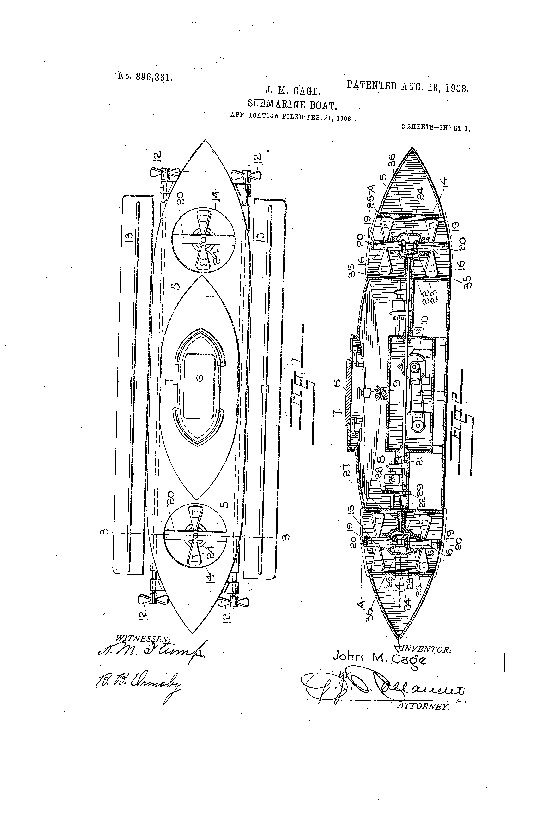

Had such books once sparked Cage's imagination? Cage's early writings (for example, "The Future of Music: Credo" [1939](11)and "For More New Sounds" [1942](12)contain lists of machines and predictions for technological improvements and often affect the objective tone of technical writing. Life, however, may have been stimulus enough, since Cage lived with the example of his inventor father and assisted him with library research for years.(13) One finds a number of parallels in the language of the two men. Cage Sr.'s first patent application boasts of "new and useful" improvements to submarine design;(14) for the son, too, the terms "new" and "useful" conveyed the highest praise.

So I try, in my life and in relation to my work, to do things that are useful (and I frequently use that word), the composer once said.(15)

Submarine Boat (1908): John Cage Sr.'s First Patent

Cage Sr. dedicated his book, Theory and Application of Industrial Electronics to his son (16) and, according to Cage, considered his son his greatest invention.(17) Cage, for his part, identified quite strongly with the label of inventor (18)and with the example of his inventor father. Speaking of the deficiencies in his musical training and abilities, the composer said that, unlike Demosthenes:

I didn't have the desire to overcome those absences in my faculties. I rather used them to the advantage of invention....I saw them as perfectly good for what I could offer the musical world--namely, invention. I knew that from my father, because I had the example every day of a person in the house inventing. And I knew that was the only thing I would be able to do in the field of music.(19)

Like Tom Swift, the son's fame as an inventor was destined to outshine his father's.

In light of Cage's adult career as radical composer and aesthetician, it is a bit strange to imagine him working for a popular, commercial radio station.(20) What else played during a typical week at KNX? According to the schedules published in Radio Digest, the programming of a typical week in April 1926 was filled with shows devoted to popular songs, to humor, and to covering "fights, blow by blow" at the Hollywood stadium.(21) "Dance orchestra" music began and ended most weekday evenings.

Cage did not remember his show as having been corporate-sponsored. However, to judge from the names of the various weekly programs listed in Radio Digest, corporate sponsorship was the rule, not the exception, at KNX.

Radio KNX in the 1920s

One naturally wonders what sort of music Cage and his fellow scouts played. The answer, in his case, was mostly piano compositions by Romantic composers. Cage recalls being infatuated with the music of Grieg at that time:

I became so devoted to Grieg...that for a while I played nothing else. I even imagined devoting my whole life to the performance of his works alone, for they did not seem to me to be too difficult, and I loved them.(22)

Cage did not remember his show as having been corporate-sponsored. However, to judge from the names of the various weekly programs listed in Radio Digest, corporate sponsorship was the rule, not the exception, at KNX. Cage's attitude toward the rest of KNX's programming seems to have been one of indifference. The composer claims to have had little interest in listening to radio, except for news.(23) He didn't care for radio comedies, although his parents did, nor was he interested in listening to music on the radio.(24) His experiences with music were mostly from live situations: taking piano lessons, going to church, and attending concerts at the Hollywood Bowl. Reflecting on his childhood in 1985, Cage lamented:

It's sad that we no longer have pianos in every house, with several members of the family able to play, instead of listening to radio or watching television.(25)

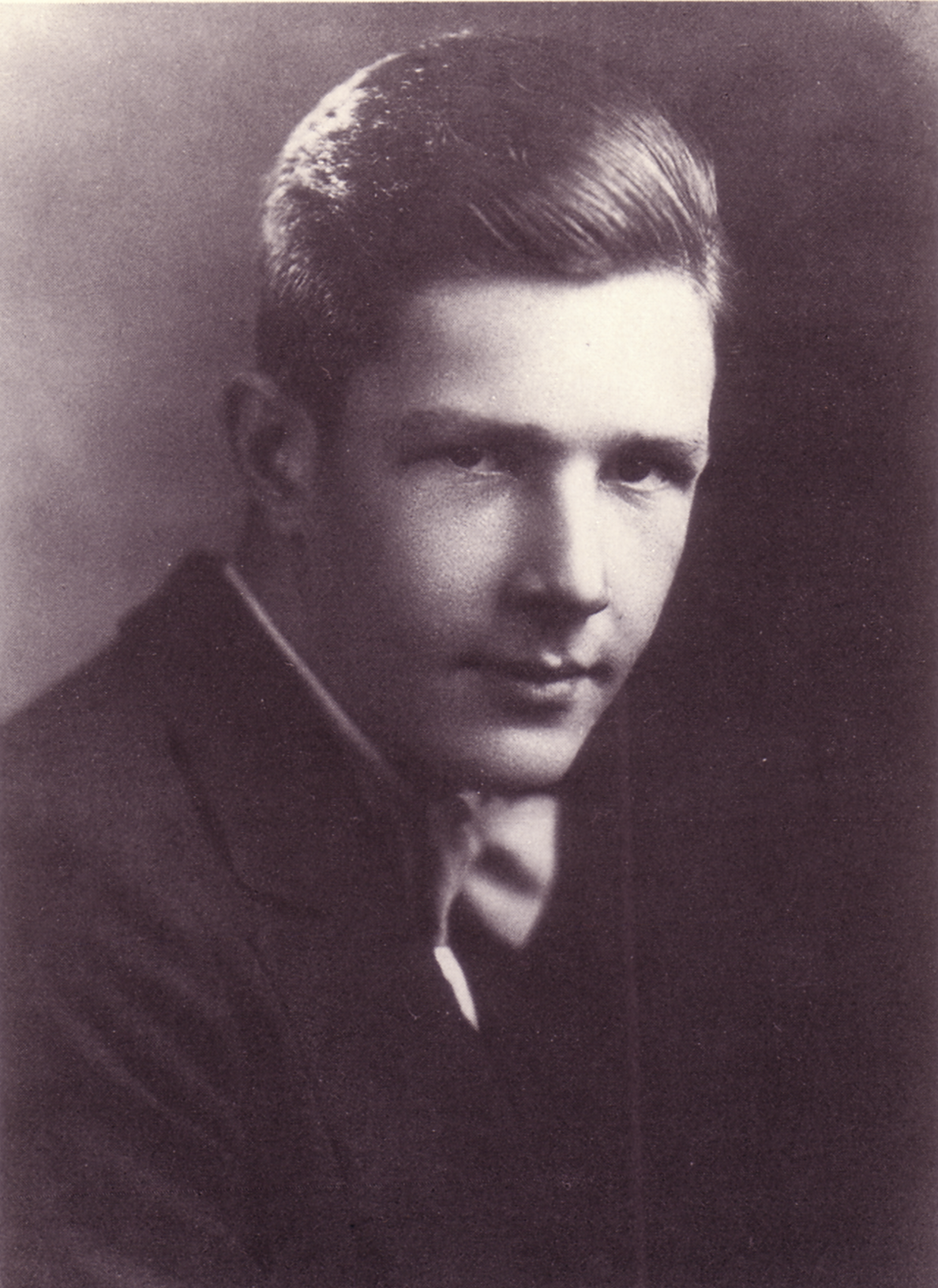

John Cage in high school

While Cage's scant published comments on his youth and radio give no indication that his love of music extended to the popular realm, neither do those comments give any indication that he was cognizant of contemporary musical radicalism (of Schoenberg's works, for example). Curiously, Cage's high school yearbook describes him as noted "for being radical." (26) What, then, is this radicalism for which he was noted? Cage's radicalism was more political and theological than aesthetic. Cage does mention a love for the films of Eisenstein, but whether the young man understood them to be aesthetically radical (as opposed to more beautiful or intelligent than Hollywood's product) is unclear. Cage confessed:

My mood for entertainment, when I was young, was satisfied by those beautiful Russian films, Eisenstein. Mostly I felt above Hollywood, where I was more or less living.(27)

Cage confessed, "My mood for entertainment, when I was young, was satisfied by those beautiful Russian films, Eisenstein. Mostly I felt above Hollywood, where I was more or less living." It ought to be mentioned that, in the 1920s, a taste for such films signaled one's political sympathies.

In the 1920s, a taste for such films signaled one's political sympathies. When Eisenstein's Potemkin received its American premiere in December of 1926, after having been banned in England and held up by United States' censors for several months, critics passed over the film's aesthetic radicalism in silence, and denounced its political radicalism and the sort of viewers that might appreciate such a work. Variety's critic, for example, wrote: "Those that are out-and-out reds, and those that are inclined to socialism will undoubtedly find great things about the picture, but to the average American, unless he be an out-and-out red, it doesn't mean a damn."(28) ______________________________________________________John Smalley holds an M.Phil. in Historical Musicology from Columbia University and has performed as vocal soloist throughout the Bay Area. In 2009, he was awarded a prestigious Shenson Performing Arts Fellowship. He regularly lectures on music and cinema and is the founder of Radical Visions Cinema Club, a 400-member organization devoted to viewing foreign and experimental films.

This essay is Part One of a three-part series Otherzine will do on John Cage and Radio. Smalley lectures at Other Cinema on Cage and Dada, April 7, 2012.

___________________________________________________________

Notes

1. Kostelanetz and Cage 273.

2. The New York Times obituary for Cage Sr. ("John Cage, Invented Submarine Devices," January 25, 1964) states that "his many patents included a radio using alternating current." However, a review by this writer of U.S. Patent Office records was unable to discover such a patent among those held by Cage Sr. at the time of his death.

3. Donald McNicol, Radio's Conquest of Space: The Experimental Rise in Radio Communication (New York: Murray Hill, 1946) 342.

4. Patent No. 1,518,688, for a condenser.

5. Francis J. Molson makes this point about Tom Swift in "The Tom Swift Books," Science Fiction for Young Readers, ed. C. W. Sullivan III (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1993) 5-6.

6. Molson 6.

7. The complete titles and dates of these books are:

8. Molson 4. At last count, four quite different Tom Swift series have appeared in print. The first series (1910-1941) was published by the Strathmayer syndicate under the pseudonym Victor Appleton Jr.

9. The views expressed in this paragraph expand on comments made by Francis Molson in his essay "The Tom Swift Books" 8-9.

10. Molson 9-10.

11. Reprinted in John Cage, Silence (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1961) 53-6.

12. Reprinted in Richard Kostelanetz, ed., John Cage (New York: Praeger, 1970) 64-66.

13. Cage credited the skills developed while researching for his father with his own ability, in the 1930s and 1940s, to keep abreast of developments in recording technology. "I did some library research in connection with my father's inventions. Because of that, when I became interested in recorded sound for musical purposes or even for radio plays, I then did library research for myself about the new technical possibilities; and they included?wire and film. Tape wasn't yet, in the early forties, recognized as a suitable musical means; but wire and film were." Kostelanetz and Cage 273.

14. Patent No. 896,361, for a "submarine boat," granted 1908.

15. William Duckworth, "Anything I Say Will Be Misunderstood: An Interview with John Cage," John Cage at Seventy-Five, eds. Richard Fleming and William Duckworth, spec. issue of Bucknell Review 32.2 (1989): 25-26.

16. John M. Cage and C. J. Bashe, Theory and Application of Industrial Electronics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1951) v.

17. Revill 21.

18. He was especially proud of the story that Schoenberg, reportedly, had called him "an inventor-of genius." Revill 21.

19. Duckworth 17.

20. In 1926, KNX was owned by the Los Angeles Evening Express, Los Angeles' oldest newspaper and a powerful commercial venture. The 500-watt station broadcast at 890 kilohertz. "The Official List of Stations by Wavelength and Frequency," Radio World 6 Feb. 1926: 11.

21. "Broadcast Programs in Advance," Radio Digest 10 Apr. 1926: 9-15.

22. Tomkins 77.

23. Kostelanetz and Cage 272.

24. Kostelanetz and Cage 272.

25. Kostelanetz and Cage 273.

26. Stevenson 6. The 1928 Los Angeles High School yearbook describes Cage with an acrostic spelling ROMAN: Recreation: orating; Occupation: working; Mischief: studying; Aspiration: to earn a D.D. [Doctor of Divinity]; Noted: for being radical.

27. Kostelanetz and Cage 274.

28. Rev. of The Potemkin, dir. S. M. Eisenstein. Variety 3 Dec. 1926.

Works Cited

"Broadcast Programs in Advance." Radio Digest 10 Apr. 1926: 9-15.

Duckworth, William. "Anything I Say Will Be Misunderstood: An Interview with John Cage." John Cage at 75. Ed. Richard Fleming and William Duckworth. Spec. issue of Bucknell Review 32.2 (1989): 15-33.

Cage, John. Silence. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1961.

Cage, John M. "Patent Number: 00896361." Patent Full Text and Image Database. 12 Feb. 2002. US Patent and Trademark Office. 18 Feb. 2002

Cage, John M. and C. J. Bashe. Theory and Application of Industrial Electronics. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1951.

"John Cage, Invented Submarine Devices." New York Times 25 Jan. 1964, sec. 2: 92.

Kostelanetz, Richard, ed. John Cage. New York: Praeger, 1970.

Kostelanetz, Richard and John Cage. "A Conversation about Radio in Twelve Parts." John Cage at 75. Ed. Richard Fleming and William Duckworth. Spec. issue of Bucknell Review 32.2 (1989): 1-305.

McNichol, Donald. Radio's Conquest of Space: The Experimental Rise in Radio Communication. New York: Murray Hill, 1946.

Molson, Francis. "The Tom Swift Books." Science Fiction for Young Readers. Ed. C. W. Sullivan III. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1993..

"The Official List of Stations by Wavelength and Frequency." Radio World 6 Feb. 1926: 9-11.

Rev. of The Potemkin, dir. S. M. Eisenstein. Variety 3 Dec. 1926.

Revill, David. The Roaring Silence: John Cage: A Life. New York: Arcade, 1992.

Stevenson, Robert. "John Cage on His 70th Birthday: West Coast Background." Inter-American Music Review5 (1982): 3-17.

Tomkins, Calvin. The Bride and the Bachelors. New York: Viking, 1965.